The Deathless by Peter Newman

It’s been just over three years since I first met Peter Newman at a Grim Gathering in Waterstones in Bristol. There, he summarised his debut novel as “A one-parent family in a post-demonic apocalypse.” That drew me into the inspirationally different story of the Vagrant, the eponymous mute hero of Newman’s revolutionary masterpiece. I followed the Vagrant and Vesper and two heroic goats through three novels and two short stories and loved every minute of it.

In October of last year at Bristolcon, Peter told me the concept behind his new novel – the idea of immortal beings whose soul is reborn through successive lifecycles into hosts chosen from amongst the children or grandchildren of their latest incarnation. Immediately The Deathless became my must-have ARC of 2018, and some far-from-subtle nudging and nagging in the end landed me both a hardback and a paperback copy! (One of which I promise to pass on at Edge-Lit in July.)

I loved the quirkiness of Newman’s first trilogy, with its terse present tense prose and utterly inscrutable protagonist in a world where demons must shield themselves with human bodies (and body parts) from an environment that is toxic to their essence. Could the new story sustain or expand on that inventiveness?

The different

The Deathless is in some ways a more conventional fantasy story than The Vagrant. The plot is driven by a human engine of desire, intrigue and politics. Familiar motivations of love, greed, power and revenge haunt the hanging castles and the wild forests.

We follow the inner thoughts and fears of four point-of-view characters:

- Lord Vasim – one of a half-dozen Deathless in the House Sapphire. A gifted flyer but drug addled and mourning the loss of his mother who was cast out, condemned to a permanent death without access to reincarnation for the crime of treating with the Wild.

- Lady Pari of house Tanzanite – confined to an aging body as she nears the end of one lifecycle yet still eager to witness, and enjoy, the safe reincarnation of the soul of her forbidden love – Lord Rochant of House Sapphire – into the body of his grandson Kareem.

- Noblewoman Chandni – Honoured mother of Lord Rochant’s youngest grandchild (and potential vessel for his reincarnation) – who finds circumstances carry her far from the comforts and respect of her castle home into rough company and even rougher living.

- Baby Satyendra – that youngest grandchild, not so much a baby as a precious commodity vital in preserving or extinguishing the line of a Deathless lord.

While there may be no goats this time around, there is an entertaining creature: Glider the dogkin, a type of overgrown hound that serves the role of part-oxen, part-carthorse, part-guard-animal. Glider has some endearing traits but, in a fit of imagination worthy of Douglas Adams, Newman gifts his dogkin with five legs and two tails. Adams has a throwaway line that at Arthur Dent’s first meeting with Zaphod Beeblebrox the galactic celebrity hadn’t got the two heads or the three arms worked well on the radio but was a special effects nightmare when the show transferred to the small (and then the big) screen. In the same way I suspect the five-legged dogkin (how do they even walk?) would prove a challenge for the (fingers crossed) eventual film adaptation of The Deathless.

While there may be no goats this time around, there is an entertaining creature: Glider the dogkin, a type of overgrown hound that serves the role of part-oxen, part-carthorse, part-guard-animal. Glider has some endearing traits but, in a fit of imagination worthy of Douglas Adams, Newman gifts his dogkin with five legs and two tails. Adams has a throwaway line that at Arthur Dent’s first meeting with Zaphod Beeblebrox the galactic celebrity hadn’t got the two heads or the three arms worked well on the radio but was a special effects nightmare when the show transferred to the small (and then the big) screen. In the same way I suspect the five-legged dogkin (how do they even walk?) would prove a challenge for the (fingers crossed) eventual film adaptation of The Deathless.

I love the inventiveness of Newman’s world – the concept of the Deathless like some form of parasitic timelords regenerated through appropriating the body of the family member most near to them in temperament and outlook (for a good match is essential to securing a successful incarnation). The victim – whose own life is extinguished in the process – is raised to regard their sacrifice as an honour to be welcomed.

Rigid hierarchies of class and status persist; families of the deathless are served in their hanging castles by a retinue of servants whose low status and finite lifespans is reinforced in the brevity of their three-letter names. It is as if Downton Abbey had been lifted into the sky and the Crawley family replaced with arrogant aristocratic ninja warriors.

I have to say Pari is my favourite character. She stands out amongst several outstanding female characters for being resourceful beyond the infirmities of age. What that woman can do armed with just two earrings would make a grown man weep (or at least cross his legs very firmly). I was too young to see Honor Blackman in her black catsuit prime elegantly kicking ass alongside Patrick McNee’s John Steed in the early Avengers series. When I saw her much later starring as a grandmother in the sitcom “The Upper Hand” she still had that classy edge with a hint of danger – and that is how I envisage Lady Pari.

I have to say Pari is my favourite character. She stands out amongst several outstanding female characters for being resourceful beyond the infirmities of age. What that woman can do armed with just two earrings would make a grown man weep (or at least cross his legs very firmly). I was too young to see Honor Blackman in her black catsuit prime elegantly kicking ass alongside Patrick McNee’s John Steed in the early Avengers series. When I saw her much later starring as a grandmother in the sitcom “The Upper Hand” she still had that classy edge with a hint of danger – and that is how I envisage Lady Pari.

There is an untold back story to this world – the Deathless are the beneficiaries and custodians of an ancient magic. This includes the godpiece artefacts – each one attuned to the soul of a Deathless, allowing their reincarnation at the first suitably auspicious occasion after each death. In return, like the patricians of ancient Rome, the exalted Deathless owe a duty of care and protection to the ordinary people in settlements huddled either side of the godsroads as they try to eke out a living on the borders of a dangerous demon-infested wild.

The familiar

As a child, I played a lot with Lego. Later, as a parent of young children, I found convenient excuses to buy and play with a lot of Lego. What struck me is the increasing variety in the little tiny bricks which made the models of today far more sophisticated and varied that the clunky combinations of simple cuboids from my youth.

Some authors, when venturing into a new series, build it on the same baseboard – the same fundamental world – in a way that reassures and comforts the reader.

Others fleck their narrative with similar motifs, the same bricks as it were, but used to make a radically different sculpture.

Others fleck their narrative with similar motifs, the same bricks as it were, but used to make a radically different sculpture.

So, too, in Newman’s The Deathless, I found nuggets of quirkiness that resonated with my memories of The Vagrant. Those distinctive features make this undeniably a Newman book (or to be more precise, a Peter Newman book).

Demons from the wild, creatures of power and ferocity, haunt the ordinary people of this world, drawn by the scent of blood on the air more powerfully even than sharks across the ocean. Newman’s demonic imagination continues the creative vein we saw with The Vagrant. His monsters, like Crowflies, Murderkind, Corpseman and Whispercage are deliciously, chaotically different.

As with The Vagrant, Newman blurs the line between good and evil. The High Lords of each of the Crystal Houses require and enforce an absolute interdiction against treating with creatures of the wild in a way that reminded me of the crusading zeal shown by The Seven against the taint of the demons. However, for those on the ground, harsh realities require compromises, and some of the demons – with strange and different powers – seem at times more compassionate than the humans.

While none of Newman’s point-of-view protagonists this time is a goat (so far), baby Satayendra is in his way as distinctive and preternatural a voice as the implant-enhanced child Vesper.

The concept of essence again seeps into Newman’s world from cracks in the earth – though in this work it is not so much a life force of living things as it is a physical power. Currents of essence wafting upwards from these chasms and above the ancient godsroads provide a magical thermal updraft. This supports the huge crystal-based castles of the Deathless families, and also provides the steady upcurrents by which the Deathless and their hunters in winged crystal suits can soar, glide and effectively fly to the aid of the people they are sworn to protect.

The Deathless, in manner and manor, are so far above the ordinary people that they reminded me of the Seven demigods of Newman’s first trilogy: Alpha, Beta, Gamma and the rest. However, the Deathless – despite their name – are not entirely immortal, and are from the outset far more active in defence of their people than the fossilised siblings of fallen Gamma (who spent two books and a couple of short stories mourning inscrutably in their levitating cubic castle/spaceship while a man, two goats and a child did their work for them).

Seven, too, seems to be Newman’s favourite number – seven crystal houses! The four major houses each have seven godpieces to elevate seven of their kin to deathless status (the three minor houses have only three godpieces each – making for some interesting political power playing and alliance building between the houses).

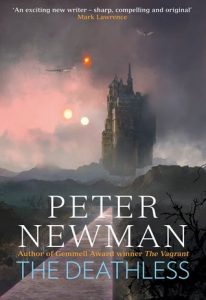

In a final after-image, the fractured sun of The Vagrant is echoed by the triple sun of the world of the Deathless, beautifully depicted in Jaime Jones’ cover. (Though multiple star systems always alarm the physicist in me, too swiftly drawn into digressions about chaotic climates, wildly fluctuating seasons and terrible tides.)

The cover

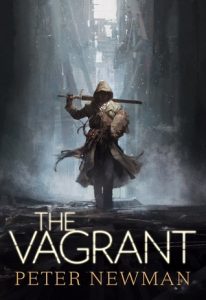

Some relationships between artist and author, between cover and story, go so deep they become more than the sum of their parts. The artist captures the essence of the book in an image that bears and rewards endless scrutiny – a picture you would happily hang on your wall. Jason Chan’s work on Lawrence’s first two trilogies was of that ilk, as was Jaime Jones’ in his haunting cover for The Vagrant and its sequels. I was delighted but not surprised to find that Jaime Jones also did the cover illustration for The Deathless. As with The Vagrant, he captures the intriguing paradoxes of Newman’s new world. The Gormenghast-like castle suspended at the end of a mathematically precise godsroad, while two winged figures swoop through a sky of ominous clouds against a backdrop of three slowly setting suns.

Some relationships between artist and author, between cover and story, go so deep they become more than the sum of their parts. The artist captures the essence of the book in an image that bears and rewards endless scrutiny – a picture you would happily hang on your wall. Jason Chan’s work on Lawrence’s first two trilogies was of that ilk, as was Jaime Jones’ in his haunting cover for The Vagrant and its sequels. I was delighted but not surprised to find that Jaime Jones also did the cover illustration for The Deathless. As with The Vagrant, he captures the intriguing paradoxes of Newman’s new world. The Gormenghast-like castle suspended at the end of a mathematically precise godsroad, while two winged figures swoop through a sky of ominous clouds against a backdrop of three slowly setting suns.

I scanned back through the Goodreads thumbnails of my recently read books to try to see the last time a cover had hit me so powerfully. I’d flicked past more than a score of books before I found one – The Malice by Peter Newman, illustrated by Jaime Jones! When I (finally) grow up, I want to have a book with a cover illustration by Jaime Jones.

An aside about second trilogies

Trilogies are a staple of the SFF genre. Through trilogies authors tell sweeping stories, tempt readers in and on. The comfort of an increasingly familiar world, a recognisable style and an appealing – or at least intriguing – cast of characters help to build a following as a sequence of books build to a crescendo. But after that peak – what next?

Where does the author go then to draw on old friends and acquire new ones? How far can they dare to strike out in new directions? Or do they try to find a different way to satisfy their base? In literary fiction the test is often the second novel, and that is also a hurdle that some fantasy authors fall at. But for SFF it is the second trilogy that tests the mettle of an author’s following – and the courage of the author in being different.

Mark Lawrence recently posted on Facebook a question about how a book might capture a magic ingredient – a difference – that would carry it beyond the boundaries of a specific genre into mainstream. Some of the reactions hint at a visceral fear of a favoured author straying beyond the fans’ comfort zone. Comments like:

“Please don’t do this, it took me a literal lifetime to find Grimdark.”

“Your style is perfect, pls pls don’t”

“I think you already kind of nailed it.”

“You’ve been incredibly successful. I think you should stick to writing what YOU want to write for the audience that you already have.”

The next trilogy/series will always be a leap of faith for the reader and a leap of courage for the writer. There may be a temptation on both parts to stick with what is known – to wring out as much story as possible from what has been proven to work. However, Lawrence drew his first trilogy to a very emphatic close – writing in his afterword “…I wanted you to part company with Jorg on a high. I would rather readers finish book 3 wanting more than wander away after book 6 feeling they have had more than enough.”

Having said that, though, his second trilogy in some ways stepped, rather than leapt away from the first – a new excursion in the same world following a different kind of anti-hero – comedic coward rather than amoral sociopath. Polynesian explorers and traders mastered the vastness of the Pacific ocean through an accumulation of short inter-island journeys, a sequence of stepping stones that eventually had taken them immeasurably far from their starting points. In the same way, a writer like Lawrence coaxes his readers by stages to travel far from the style and milieu in which they met him (though with no diminution in the constant quality of his writing).

Other writers and readers find themselves trapped within an original series – succumbing to series sprawl – where successive books are subdivided into ever more volumes (here’s looking at you, GRRM). Or – having rounded off an epic tale in some style – the author struggles on their own account to find new ground to explore, new characters to be passionate about. Maybe this fear is what leaves some writers stalled on the crest of book three – not just the fear of failing to do justice to what has gone before, but the fear of finishing a journey. In either case – be it the long-awaited final volume, or the fresh breath of a new series – authors risk their following drifting away and finding new loyalties as an old favourite silently pleads “I need more time.”

And in the context of The Deathless?

These thoughts and more whirled around in my head as I rattled through The Deathless – itself produced with impressive swiftness hot on the heels of The Seven, the final volume in the Vagrant’s story.

Newman’s writing is smooth and assured. It cradles the reader’s immersion in the story and yet brandishes flashes of humour in the character’s interactions.

“Oh Varg, am I really that difficult to be around?”

“No,” he replied, a beat too late to be convincing.

(Now who amongst us has not had that experience of saying the right thing too slowly? Or indeed saying the wrong thing too quickly!)

There had been many stories about goodhearted travellers being lured to their doom by monsters wearing a human face.

“Quickly,” she added, “before it gets me.”

“How’d I know you’re a person, straight and true?”

“If I was of the Wild I’d talk less and look much more appealing than this.”

“Thas fair,” said the man, and leaned out, his hand open…

The overall effect is pretty damn good. This is an excellent book which will, I am sure, draw in new readers to an appreciation of Peter Newman’s creativity, as well as more than satisfying those of us who first found him through The Vagrant.

The Deathless by Peter Newman will be released on June 14th 2018.

[…] revealing some of the first book’s endpoints. So, you can see my review of The Deathless here and may wish to buy and read that book before going on to the rest of this review. […]

Wow. Great review! I learned more about Peter in this and the FH author interview here today than in two years of recommendations and comments in groups. Bravo.

Thanks so much, Lynn! Our T.O. really does write great reviews, and the Author Spotlights are always so much fun to do. Glad you enjoyed both!

[…] It sounds amazing! (Our reviewer T.O. Munro certainly enjoyed it; you can read his review here.) […]