Kingdoms of Elfin by Sylvia Townsend Warner (Book Review)

I am entranced and fascinated by stories about fairies and the mythology that surrounds them. I have enjoyed a wide range of reimaginings and retellings of fairy myths that vary wildly in style and execution, but I am an absolute stickler for one thing – the author has to get fairies right. They have to properly understand them. By which I mean, the thing about the fair folk is, they are charming and enrapturing, but they are also very very inhuman. They have no souls, they are cold and frightening and often malicious. They adhere strictly to the rules of folklore and myth that define them, but their morality is entirely outside that of humanity’s. As such they can be malicious, capricious and deceptive, or just plain destructive through an inherent misunderstanding of humanity. But one thing fairies are emphatically not is nice.

I am entranced and fascinated by stories about fairies and the mythology that surrounds them. I have enjoyed a wide range of reimaginings and retellings of fairy myths that vary wildly in style and execution, but I am an absolute stickler for one thing – the author has to get fairies right. They have to properly understand them. By which I mean, the thing about the fair folk is, they are charming and enrapturing, but they are also very very inhuman. They have no souls, they are cold and frightening and often malicious. They adhere strictly to the rules of folklore and myth that define them, but their morality is entirely outside that of humanity’s. As such they can be malicious, capricious and deceptive, or just plain destructive through an inherent misunderstanding of humanity. But one thing fairies are emphatically not is nice.

Sylvia Townsend Warner understood this better than most. Written at the end of her life and published mostly in the New Yorker, the stories in Kingdoms Of Elfin by Sylvia Townsend Warner are a unique and striking take on fairy mythology. Across these sixteen short stories, Warner explores fairy civilisation, which exists alongside human history but entirely separate from it. While other writers have beautifully captured the frightening and capricious nature of fairies, the brilliance in Warner’s stories lies in how the stories themselves are infused with the cold otherness of fairyland. Warner’s stories explore the foibles of fairy society, the lives of its courtiers and commoners, the adventures and exploits and even love of its inhabitants and the disasters that befall when the worlds of human and fairy interact, all with beautifully wrought language and a wry, impassionate eye. Her beautiful evocative prose and fanciful imagination draw us in even as her cold and unknowable narrative voice drives us away, much like the dangerous allure of Elfindom itself. Emotional response, that most human of reactions, is left entirely to the reaction of the reader.

Warner’s stories chronicle the lives and customs of the fairy courts of Elfame in Scotland, Brocéliande in France, Zuy in the Netherlands, Gedanken in Austria and Blokula in Lapland. The fairy courts are vain and fickle, born with wings but refusing to fly as flying is the mark of fairy commoners. Warner explores their petty rivalries and silly games they play to keep themselves amused across their long lives, the rises and falls in fortune of various courts, and their rare but destructive entanglements with the lives of mortals. Wryly humorous, the stories eschew the quest motifs and structures of much fantasy to give a record of the lives and customs of the fairy courts. The unusual structures and surprising ends of the stories nicely reflect the alienness of the characters and the narrator – what is important and significant in fairyland is not necessarily what is important or significant to humans. Many of the stories derive a strangely affecting pathos from this – the narrator is frequently unmoved or blasé about the short-lived victories of love in ‘Elphenor and Weasel’ or the tragedies of defeat suffered by the characters in ‘Winged Creatures’.

The stories are immersed in folklore, from the Child ballads to King Arthur to Robert Kirk’s The Secret Commonwealth. These sources inform and shape the stories, but in an original and oblique way. After all, our stories are about human contact with fairies from the human perspective. In Warner’s stories, the myths and legends we are familiar with happen on the outskirts, their importance to human culture and the human characters caught in the web insignificant to the fairies’ very different interpretation of them. The fairy scholar in ‘The Occupation’ scoffs at Kirk’s simplifications and errors in The Secret Commonwealth; as humans misunderstand and misinterpret the motives of fairies because they are so different, similarly the fairies looking back at humanity misunderstand and misinterpret us.

When human and fairy interact, as in ‘The One And The Other’, staring at oneself reflected in the mirror of so alien a people brings about a profound existential crisis for both fairy and mortal. Identities are swapped and confused. The fairies’ cruel treatment of Changelings, keeping them as amusements who have no chance of being fully a part of the fairy world and discarding them as soon as they show signs of age, reflects humanity’s own cruelty towards those it deems ‘other’. In the final story, ‘Foxcastle’, James Sutherland is consumed by a fascination and a longing for the land of fairy. When he is brought into it, the price he will pay is that he will eventually be exiled back into the world of humanity, no longer able to fit in. This reflects our own fascination with the world of Elfindom. As with Sutherland’s experience, Warner’s stories can only show us beautiful captivating glimpses that repel us as soon as they’ve dragged us in.

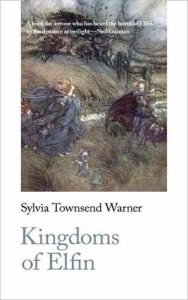

Handheld Press’s new edition is a handsome book, with a cover illustration by Arthur Rackham, extensive footnotes, and informative foreword and introduction by Greer Gilman and Ingrid Hotz-Davies, which contextualise the stories for modern readers. Overall it’s a thoughtful and well executed reissue of a lost classic of the genre.

[…] the changes between versions. As with their superlative edition of Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Kingdoms Of Elfin, the cover art is beautiful, the text is helpfully and informatively annotated, and there is an […]