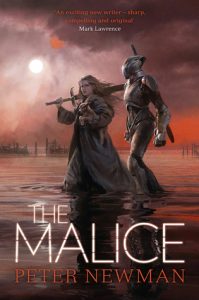

The Malice by Peter Newman

Peter Newman has followed up his remarkable debut The Vagrant with another exceptional tale: The Malice.

Peter Newman has followed up his remarkable debut The Vagrant with another exceptional tale: The Malice.

In The Vagrant, Newman flouted convention with a present tense story of a protagonist who was not only mute, but whose point of view we never saw. Newman decided that we would only know his eponymous hero by his deeds, rather than his thoughts or words. As Sir Humphrey Appleby might have observed in Yes Minister it was a brave authorial decision, one which I hadn’t seen since Malcolm Bradbury’s The History Man.

Add in a baby, a feisty goat and a singing sentient sword and Newman had a debut that stretched the envelope of traditional fantasy in new directions.

It made for a hard act to follow, and yet in The Malice Newman still manages to strike off in a new enthralling direction in the same demon blasted world.

At first sight he has abandoned the mute hero. The setting is some years later and it is the baby Vesper who has become a girl who takes up the sword, some outsized clothes and a handful of companions including a taciturn soldier called Duet and – inevitably – a goat. But Vesper’s tumble of emotions is laid bare for the reader as she struggles to do right in the face of new threats and a confusion of allies.

The world of The Vagrant and The Malice mixes elements of fantasy and science fiction as swords and armour jostle alongside sky ships and robotic prosthetics. But at the heart of it is still a story of people – of conflict and fear, love and duty.

As with The Vagrant, Newman pursues two timelines. But this time the past timeline is set over a thousand years earlier. For those who love their detailed worldbuilding, The Vagrant – both book and character – could have proven frustratingly enigmatic. There were no great info-dumps, no ponderous retelling of history in the convenient guise of a bard in a bar singing for his supper. The backstory was delivered through glimpses of a world that was and the world that it had become. Of an empire that had been waiting for an invasion – expecting it – yet ultimately failing utterly to contain it and the consequences of that failure. It was still a partial perspective, one that raised questions even as the reader savoured the rich inventiveness of the setting.

In The Malice, Newman gives us more insight into that backstory with an episodic tale of events over a thousand years in the past. While Vesper treads her path in the present, a remarkable individual Massassi grows up in a world that knows nothing of the breach or the threat of demons. It transpires that the humans of Newman’s world are creatures of essence too – just like the demon invaders – a spirit presence encased in a shell of flesh such that only some can see it or even shape it.

There are other ways in which the humans seem less different to the demons, less heroic, less worthy as we go through this second book. The Vagrant, had echoes of the enigmatic hero of Stephen King’s The Gunslinger and the fractured pockets of civilisation we saw in Mad Max’s post-apocalyptic world. In The Malice there are resonances with Aldous Huxley’s A Brave New World or even Orwell’s 1984. Though different, neither the civilisation that Massassi was born into, nor the world that Vesper grew up in, are entirely benign. In different ways they control and exploit, denying human individuality, rejecting the kinship of families. Suddenly the demons – while hardly good – seem a lot less bad, and – for both demons and humans, there are worse enemies than each other.

My favourite characters were those that had accepted that new reality – that the old world was broken beyond repair and new ways of living, of existing, needed to be found. None more so than in Verdigris where the struggles of half-breeds and humans come under the inspirationally pragmatic leadership of Tough Call. However, not all are prepared to relinquish power, not all can see the greater threat that could destroy them all.

There is a risk in saying too little that the story might seem a simple one. The Vagrant travelled North; Vesper travels South. However, it is much more than that and there is a risk in saying too much of spoiling a reader’s discovery of Newman’s inventiveness. This is a very individual book by a writer with a unique style. Suffice to say that if you liked The Vagrant you will love The Malice.

I said at the start that Newman had abandoned the mute hero motif, but that is not strictly true. For this book is called The Malice, not Vesper. It is the sword that drives the story, that calls to Vesper and her father, that yearns to be used. We knew something of the Vagrant through the choices we saw him make, but the Malice is a more inscrutable and demanding protagonist. It is much more than a sword. It holds the last fragment of Gamma, champion of The Seven with whom it was paired and to whom was assigned the honour of fulfilling the Empire’s entire purpose once the breach ruptured. The struggle between Vesper and the Malice as each strives to do what they consider right is an intriguing one – the child against the last relic of a demigod.

Newman brings The Malice to a satisfying conclusion, but one that sets up questions for the final part in his imaginative trilogy. It is time for The Seven to come forth and face a changed world and for us to find what part they will play in its future. There is more backstory still to be told and perhaps, when Newman has revealed fully where the Seven came from, we might guess at what choices they will make as the shrunken Empire of the Winged Eye faces an increasingly perilous future. I can’t wait to see it.

This review appeared on Fantasy-Faction on May 31, 2016.