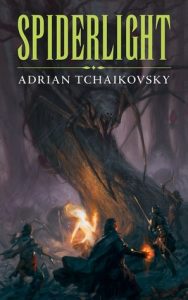

Spiderlight by Adrian Tchaikovsky

So, that Adrian Tchaikovsky is a clever bloke.

So, that Adrian Tchaikovsky is a clever bloke.

He tricked me (and plenty of others, no doubt) into thinking Spiderlight was a tropey, cliched, rose-tinted throwback to the ‘good old days’ of D&D. You know the days: when men were men and spiders were spiders and women were damsels in distress and mages were all arrogant moustache-twirling arseholes who were unlikely to ever voluntarily lift a finger to help their companions unless there were something in it for them.

Now is probably a good time for me to hang my head and confess that I’ve never engaged in a single tabletop game in all the twenty-eight long years of my life. However, I’ve played my fair share of PC RPGs like Icewind Dale and Baldur’s Gate and Neverwinter Nights; I also watched that one episode of The IT Crowd where Moss introduced a boisterous bunch of randy businessmen to the unexpected joys of roleplaying (‘This seems . . . gay!’; ‘Are dragons gay, Phil?’).

What I’m saying is that I know enough to recognise that Spiderlight is a homage to the genre, one which places neat twists on classic tropes and character roles whilst also managing to retain the positive atmosphere and (presumably) satisfactory resolution of a role-playing campaign.

Until I realised Tchaikovsky’s endgame – namely, to create a pastiche of traditional fantasy that entertains as much as critiques – however, much of the dialogue just made me cringe.

“We will follow this path, and trust to prophecy.”

“There’s a lot of Dark territory between us and the Shadow Canyons,” Lief pointed out unhappily. “Ghants and blight-wolves and Murgl-wyrms and all sorts.” His finger traced a line from Shogg’s Ford, showing the route. “Not convinced that the power of prophecy’s going to get us through all that.”

“It will be an epic journey,” Harathes said potentiously. “A worthy quest, through monsters and the servants of the Dark one, past evil forests, marshes, and jagged rocks . . .”

“Mm.” Lief grimaced. “You’re not selling it to me.”

It took a while before I was 100% sure that the cheese was deliberate, but several chapters later I was finally sold. As you can see, Spiderlight is almost distractingly self-aware; this is evident everywhere from the story’s structure to the chapter titles themselves. ‘Mirkwood Blues’, ‘Fear and Loathing in Shogg’s Ford’, ‘The Third Rule of Arachnophobics’ and ‘Fear of a Dark Tower’ – a somewhat motley mixture of references to pop culture, well-known authors and genre classics.

Meanwhile, there’s an undercurrent of gentle irony that brings to mind the writing style of Diana Wynne Jones. In fact, Spiderlight is about as close to a novelisation of The Tough Guide to Fantasyland you’re likely to find; Tchaikovsky presents to the reader a veritable buffet of archetypes, which he then proceeds to pick apart and improvise with. In contrast to the growing trend of grimdark ANTIHEROES (see also: MISERABLE BASTARDS) and NIHILISM, Spiderlight is instead a nice way of poking fun, and is much more celebratory of the genre’s good intentions even as it works to subvert them.

The characters themselves are, initially, little more than caricatures. To lead the party, the author rolled a lawful good human cleric named Dion. In fact, at first glance the entire party looks to have sprouted from The Tough Guide to Fantasyland, including Dion (the CLERIC), Cerene (the IMPERIOUS FEMALE) and Penthos (the MAGICAL ADEPT).

“When Dion considered the world, her chief question was, Is this of Light or Dark? Penthos’s main interest was usually, Is this flammable?”

The characters continue behaving according to their prescribed roles for quite some time, which leads to a fair amount of amusing dialogue – such as during this exchange between Lief (ROGUE, human, true neutral) and Penthos (MAGE, human, chaotic neutral):

“It stinks of magic.”

Penthos gave him an arch look. “And you’d have a sensitivity for magic?”

“It has floating lights, and that bloke over in the corner is wearing a crown of glowing ice, and his mate’s got the head of a parrot. I don’t think you need to be Grand Archmage Woddleflot to pick up the delicate scent of magic.”

But while this is undoubtedly entertaining, it’s not enough to maintain the reader’s interest throughout the entire story. Thankfully, just when you’re beginning to doubt the author’s intentions – when you’re teetering back towards your initial assessment of Spiderlight as a two-dimensional nostalgia trip – the characters begin to wander off script. This is largely down to the fact that one of their party members is, in fact, a spider (Nth the spider, to be precise, whom the other characters dub ‘Enth’).

At first, it’s small things, like the humorous dialogue (which we’re by now familiar with) taking some unexpected turns:

“Another?”

Nth understood that this meant more beer. To his surprise, his mouth opened and words came out. “I like beer.”

Lief’s expression lit up. “Good for you.”

“I like you, too. You make beer happen.”

Aside from the obvious hilarity of the premise (how do you bond with a spider? Go out and get drunk together, of course!) this scene is a pivotal moment in the story. The normality of the situation – two new comrades, chilling and drinking beer and getting to know one another better – set against the backdrop of a world-spanning ‘good vs. evil’ conflict resonates in a similar way to the famous ceasefire/football match during WW1. Though this juxtaposition creates humour, it also demonstrates the potential for common ground between characters who, according to the ‘rules’, should not even survive their first meeting – just like the British and German soldiers who decided to have a kickabout in No Man’s Land on Christmas Day, 1914.

While some of the characters never really develop into much more than their archetypes, it’s enough that we see the unique and changing perspectives of the others, and that we understand why each character thinks and acts in certain ways. Cerene is a woman in a man’s world, and has spent years fighting the same old labels that still plague the genre today – namely, that if a woman has sex with you but later refuses to marry you (or, even worse, she has sex with somebody else!), then there’s either something wrong with her, or she’s a whore. Harathes sees the world in black and white, and genuinely can’t understand why Cerene isn’t grateful for his advances; he’s hurt that she flirts with other men despite ‘belonging’ to him, and claims to love her even as he violently attempts to stop her from making her own decisions.

And Enth – poor Enth! – forced from his forest home, transmogrified into an unfamiliar shape because the ‘good guys’ can’t accept him for who he is, overwhelmed by the world and horrified by the crowded, claustrophobic cities that dominate the enemy territory he’s being dragged through.

“It was a nest, a crawling nest of Man. Here they had grown filthy fungal-looking excrescences in profusion, and then they had bred and festered until the entire hideous hole of a place was overrun with a scurrying tide of four-limbed, flabby-skinned Man-creatures.”

In the end, Spiderlight shows us the various facets of what it is to be ‘human’. Through the growing relationship between certain party members (which is surprisingly heartwarming), Tchaikovsky demonstrates that not everyone who fights for ‘evil’ is inherently evil themselves. Whilst celebrating the influences – Gary Gygax, J.R.R. Tolkien, Dragonlance, Diana Wynne Jones, Terry Pratchett – that make this genre great, Spiderlight also gives it a gentle nudge in the right direction. Just like in real life, some characters are much more receptive to change and progress than others, and are more willing to embrace diversity. And just like in real life, the characters who choose to respond positively are not always necessarily the ones you’d expect to. The latter is yet another tug of the rug beneath our feet – because isn’t the whole point of ‘classes’ and ‘alignments’ so that we can pigeonhole and predict a character’s every interaction? How else are you meant to plan a campaign without everything going tits up?

Spiderlight shows us that ‘tits up’ is exactly what the genre needs. Tchaikovsky isn’t just tearing out the algorithms; he’s subtly messing with them, tracing the problems right back to their foundations and making tweaks here and there so that things might just play out differently next time. Most importantly, he shows us that just like identity, alignments are non-binary, and perhaps should not exist at all.

Enth’s story is not so much ‘out with the old, in with the new’ as it is about blending the best of both to tell a story about light, dark, and all the shades of humanity that make up the layers in between . . . if only you look close enough.

Yep; that Adrian Tchaikovsky is a clever bloke indeed.