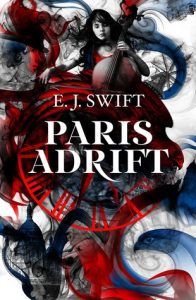

‘Conditions for Vision’: Guest Post by E.J. Swift

In the opening essay of her collection On Writers and Writing, Margaret Atwood discusses a series of interviews where she asked writers to describe how it feels going into a novel. She summarizes the responses:

“Obstruction, obscurity, emptiness, disorientation, twilight, blackout, often combined with a struggle or path or journey – an inability to see one’s way forward, but a feeling that there was a way forward, and that the act of going forward would eventually bring about the conditions for vision.”

I love this quote because it encapsulates so perfectly the emotional journey of writing a novel, and I often return to it at the start of a new project, where the task ahead can seem gargantuan, or at one of the inevitable sticking points along the way.

By the end of a novel its beginnings are sometimes obscured; it might be a concept, a feeling, a scientific theory, a sense of place or of character that sparks the impetus to write. Paris Adrift was unusual in that my experience of living in the city was that spark. By contrast, my approach to writing hasn’t altered much over the years: I might wish to be organized and efficient, but the reality is it’s an unstructured, fairly chaotic process.

With a new novel I have to write my way in. Sometimes I have a loose idea of story, but more likely I’m following an instinct of voice or theme and seeing where it leads. In the first draft, I don’t worry about the quality of the writing, my aim is to get words down on the page. I write scenes or chapters as they occur, out of sequence. I know the book is embedding when lines start popping into my head at random times (usually in the middle of the night, when I’m least likely to write anything down. I’ll remember in the morning must be the writer’s great lament).

Once I’ve reached a certain critical mass of material, I’ll have a sense of where the story is going, and that point I’ll take a step back and think more carefully about plot, though I’ll continue to write scenes at random. I’ve always enjoyed crafting endings, and often the ending is one of the earliest scenes I’ll write. The content of this may change, but it gives me an idea of the note I want to land on.

Getting the first draft down is the biggest milestone, because although there’s still a long way to go, at this point I feel I have something viable to work with. I can start to sculpt, tightening the story, teasing out themes and seeding plot points. At this stage I may also cut a lot of material. Paris Adrift lost around 25,000 words from the start after feedback from beta readers, who quite rightly pointed out that it was unnecessary backstory. One of those chapters was from the point of view of my narrator, Hallie, as a child. It was eventually condensed into a couple of pages of reflection which appeared much later in the book, but the experience of writing that chapter was a valuable exercise in thinking about Hallie’s background, personality, and crucially, what she is running away from.

Before the book goes to my agent, I’ll do another edit incorporating feedback from beta readers and polishing up the text. At this point I’m looking at the fine details – the rhythm of the sentences is hugely important, and technical edits like catching repeated words or over-reliance on certain phrases or structures. I’ll do a lot more of this down the line when working with a professional editor.

By the time the book’s been signed off for print, it’s been through at least seven or eight revisions (hatred and/or a feeling of Stockholm Syndrome for the manuscript are not uncommon by this point). When the finished, printed book arrives, I’ll never look at the actual text, because there’s always something you’ve missed or that you know you could improve. Despite all the sweat and tears and anguish along the way, letting go is the hardest part.

E.J. Swift is the author of Paris Adrift, which is out now.