Vancian Magic and D&D

My very first introduction to D&D and its magic system came from the Dead Alewives’ parody “Dark Dungeons,” which can be summed up with the following excerpt (courtesy of The Obsolete Gamer):

D&D Player 1: “I wanna cast a spell!”

D&D Player 2: (shouting from the kitchen) “Can I have a Mountain Dew?”

DM: “YES! You can have a Mountain Dew, just go get it!”

D&D Player 1: “I can cast any of these, right? On the list?”

DM: “Yes, any…any of the first level ones.”

D&D Player 2: (shouting from the kitchen) “I’m gonna get a soda, anyone want one? Hey Grimm, I’m not in the room, right?”

DM: “What room?”

D&D Player 1: “I wanna cast ‘magic missile…’”

D&D Player 2: (shouting from the kitchen) “The room where he’s casting all these spells from!”

DM: “He hasn’t cast anything yet!”

D&D Player 1: “I am though, if you’d listen. I’m casting ‘magic missile!’”

Years later, after creating pyramids of Mountain Dew cans during D&D sessions and being reported for gambling at a campground (we were rolling polyhedral dice), I learned that the Dead Alewives pretty much nailed what D&D is all about, down to the confusion over the magic system.

Magic in D&D is usually based around levels and spell slots—a Level 4 Wizard might have access to dozens of spells, but they only have a small number of spell slots. At the beginning of each day, they have to prepare whatever spells they think they’re going to use, equip ‘em to their spell slots (guided by a confusing spell table), and head out into the world. Each spell can only be used once a day, however—meaning that even if the spell misses, it’s gone until the next long rest.

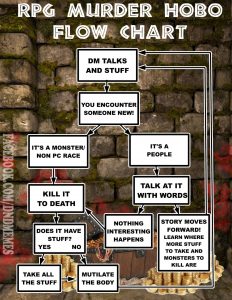

5th edition D&D has made a lot of improvements, but at heart, magic in D&D tends toward bookkeeping (ie, minutiae) and powergaming (ie, taking advantage of the game’s mechanics). At worst, magic becomes just another means to advance the Murder Hobo flow chart.

That’s sad, because one of the primary inspirations for D&D’s magic was the Dying Earth series by Jack Vance, whose magic is actually pretty interesting and nuanced. The Evil GM blog has already done a fantastic rundown on the history of how Jack Vance’s signature magic system became adapted for the game (and the problems it creates for game balance), but that’s not what I’m gonna talk about here. We’re gonna look at the bigger picture: what are the cool things to take from Vancian magic?

Jack Vance’s Magic System

There are a few key features to the system:

- Spells are made up of words and syllables, and mages can have access to dozens of spells.

- Spells (at least those written down) are akin to living things, and have their own will.

- Mages can only “memorize” (or “prepare”) a few spells at a time due to their immense power.

- Mages can trigger a “memorized” spell once it’s been prepared, but lose use of it until they’re able to prepare it again.

Here’s a passage that shows what it’s like when a mage interacts with spells:

Turjan found a musty portfolio, turned the heavy pages to the spell the Sage had shown him, the Call to the Violet Cloud. He stared down at the characters and they burned with an urgent power, pressing off the page as if frantic to leave the dark solitude of the book.

What’s most interesting in this passage is that the spells are trying to escape the book—they’re not inert computer code or abstract truths written in ordinary ink. They’re almost animate, like creatures. It reminds me of a practice used by the Sami, an indigenous people of Scandinavia, which is called the yoik (or joik). A yoik can be understood as a song that evokes something or someone:

A yoik is not merely a description; it attempts to capture its subject in its entirety: it’s like a holographic, multi-dimensional living image, a replica, not just a flat photograph or simple visual memory. It is not about something, it is that something. It does not begin and it does not end. A yoik does not need to have words – its narrative is in its power, it can tell a life story in song. The singer can tell the story through words, melody, rhythm, expressions or gestures.

The idea is that words connected to something, when spoken, bring that thing into being by changing reality. It’s a different idea than converting magical “energy” into an effect, like a fireball—conversion of energy to energy or mass is fundamentally different from changing reality itself.

Vance’s magical syllables aren’t powerful because they give access to greater abilities, they’re powerful in themselves, and the danger doesn’t come from misusing them, it comes from interacting with them—even the process of preparing a spell in one’s mind can drive a mage mad.

The Universe is Magic, and Magic is Math

The most interesting thing for me in Vance’s system is the connection he draws between math and metaphysics. Check out this passage:

He learned the secret of renewed youth, many spells of the ancients, and a strange abstract lore that Pandelume termed “Mathematics”.

“Within this instrument,” said Pandelume, “resides the Universe. Passive in itself and not of sorcery, it elucidates every problem, each phase of existence, all the secrets of time and space. Your spells and runes are built upon its power and codified according to a great underlying mosaic of magic. The design of this mosaic we cannot surmise; our knowledge is didactic, empirical, arbitrary…He who discovers the pattern will know all of sorcery and be a man powerful beyond comprehension.”

“I find herein a wonderful beauty,” he told Pandelume. “This is no science, this is art, where equations fall away to elements like resolving chords, and where always prevails a symmetry either explicit or multiplex, but always of a crystalline serenity.”

There’s a lot of people who think any connection between magic and mathematics ends up running into a kind of parallel to Clarke’s Third Law (“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”): if magic is just math, then computers are magic, and so is technology.

I think that kind of reductionism is bullshit. Whatever magic is based on, whether it’s mathematics, ki, or singing yoiks, the important thing is that you’re not just creating a magic system, you’re saying something about the world. In the above passage, the main idea isn’t how mastering mathematics will make a mage ‘powerful beyond comprehension,’ it’s about how it reveals the true nature of the universe (which naturally makes someone powerful). The mage in question realizes that the mathematical patterns in magic connect everything in creation, and that’s a much deeper statement than “math = magic.”

If there’s one thing to take away from Vance’s magic, it’s not the spell slots or making magic into an occult branch of computer science, it’s that line “This is no science, this is art, where equations fall away to elements like resolving chords.” It evokes a sense of cosmic awe and mystery that you don’t get from rolling three d4 dice.

Unless your DM is damn good at his job.

The parody wasn’t done by “The Dead Alewives,” that was a joke name for the religious organization in the sketch… the parody was done by the Frantics.