Linggi River Blues (Guest Post by Zedeck Siew)

The Linggi River winds through Negeri Sembilan, my home state. It is not safe to swim. Waste from the fishing industry downstream feeds an exploding population of saltwater crocodiles.

There is a sacred site, seven miles upriver. In the same place, around a freshwater spring, the tomb of a Sufi saint sits next to a trio of naga-shaped megaliths sits next to a court of Chinese folk deities.

But the official religion of the Federation of Malaysia is Islam. And – since the revivalism of the 1980s – syncretism does not sit well with official Islam.

The Chinese shrine is moved. The Muslim shrine ceases to be a shrine; now it is an archaeological site. The megaliths are not recognised as nagas, but are said to be “shaped like spoons”.

+

“Serpent, Crocodile, Tiger” stays close to the facts of this sacred, contested space.

Its fiction speculates about how such a place might have come to be; about the people that might claim its meanings; about the reasons why.

+

The story is one long thing, split up into four things:

A etiological tale – “How Tiger Bluffed Herself Into Being”, basically;

A hikayat-like romance between a Minang princess and a crocodile;

A person-of-colour-student-partying-in-1970s-London narrative;

A rural fantasy, set in small Negeri Sembilan town.

Interspersed between these are lengthy excerpts from three separate fictional ethnographic texts, written in the academic voices of three different colonial phases:

Empire;

The post-colonial era; and

Our Post-Colonial, Said-inflected reality.

It is a mythic history – and historiography! – compressed into 8,000 words. Which is kind of dense, I guess.

+

“Serpent, Crocodile, Tiger” is very placed in its particular geography. Re-reading it now, I worry that the story doesn’t explain enough for a Western reader.

Where is Mt Korinchi? Who are the Bugis? What is a Na Tuk Kong? Stuff like that.

I might say this obfuscating specificity is a rebuttal of Kipling. He was Imperial Britain’s storyteller; he dragged its far-flung subjects home, headdresses in hand, to dance for Albion’s children.

The inheritors and beneficiaries of that colonial legacy have never needed to leave their drawing rooms, since. (Or, as the case may be, their holiday backpacker-slash-Airbnb ghettos.)

So this might be my attempt to drag Western readers out into a different world. A world both just a Google away – yet farther than Valinor, more distant than Gethen.

+

But, honestly:

While I was writing “Serpent, Crocodile, Tiger”, I wasn’t really thinking about Western readers.

I wrote this story to work through the complex feelings I have about Kipling, who I grew up with. And about Skeat, the English anthropologist, whose book Malay Magic is still one of my favourite things.

(Skeat was Kipling’s source for “The Crab That Played With The Sea” a Just So Story that also happens to be super racist towards Malay people. Shout out to Adiwijaya Iskandar, whose “The Man Who Played With The Crab”, also in this collection, is such a direct and delicious send-up of that story.)

How can I, as an Asian person, possibly continue loving Kipling, or Skeat?

+

I think I wrote “Serpent, Crocodile, Tiger” to speak to me. People like me – here, in the East. With my deep, enduring need for a relationship to the West.

To measure against it;

To be legible to it;

To be acknowledged by it.

Du Bois described the double-consciousness of African Americans, a sense of “always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others”.

Whiteness holds hegemony in Southeast Asia, as anywhere else – but by and large there is space.

Day to day, I can afford to ignore the term “people of colour”. Day to day, in the town where I live, the people I meet and eat with are Tamil and Minang, Sikh and Hokkien. I myself am Hakka. Brownness – in the POC, compared-to-whiteness sense – is too abstract to be useful.

So why, in my thinking, in my fiction (always in the English language), in my participation of various online communities, do I crave and readily slip into the performance of a brown identity?

Why does it matter so much, how I look to whiteness?

What does being seen by whiteness confer? What power do I siphon from that recognition, to wield here, at home, where I am?

+

In my story, Tiger is an in-between creature. Maybe a tiger, or a crocodile, or a human being. Maybe a she, maybe a he.

Tiger appears in dreams and claims to be a god. Tiger changes shape, and tells stories, and lies. In front of a mirror, Tiger preens. For pleasure. For nobody but herself.

+

(This story would not exist without artist Simryn Gill, who took me to see the shrines, told me the stories, and let me borrow the books.)

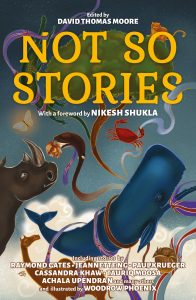

Zedeck Siew’s story “Serpent, Crocodile, Tiger” appears in the Not So Stories anthology, available now from Rebellion Publishing.