A Book and a Film: The Man Who Fell to Earth

I can’t remember exactly when I first saw the film of The Man Who Fell to Earth – back in the 1980s, I guess, when TV channels were fewer and films were more special. I didn’t see it all, though. I came in about half way through and I must have missed the end. But that fragment of a film still left a seed of powerful images and scenes lodged in my head – aided no doubt by David Bowie’s haunting performance as an extra-terrestrial of a far more human mould than Stephen Spielberg’s ET, yet still undeniably alien.

So, seeing the book recently on a Sci-Fi classics shelf in a bookstore, I was curious enough to read the original source material and then re-watch the film.

The book (by Walter Tevis, 1963)

The book (by Walter Tevis, 1963)

The book’s opening is set in 1985 – 22 years in the future at the time Tevis wrote it, yet still a year the author did not get to see, dying of lung cancer in 1984. It is a short and pithy read of 209 pages, focused, to my eye, more on its alien ideas than character or writing. But it has lines that still appeal:

“He had discovered, quite by accident, that it could be a fine thing on a grey, dismal morning – a morning of limp, oyster-coloured weather – to be gently but firmly drunk.”

Elsewhere Tevis pokes fun at the

“… great labelling shift that turned every salesman into a Field Representative, every janitor into a Custodian … there were no more secretaries, only Receptionists and Administrative Aides, no more bosses only Co-ordinators.”

The book lets us follow the thoughts of: Thomas Jerome Newton (the name that the man who fell to earth gives himself); Oliver Harmsworth – the lawyer through who Newton manages his growing technological empire; Nathan Bryce – a disillusioned university chemistry lecture chasing a place in Newton’s impossibly advanced organisation; and Betty-Jo, a woman drawn by accident into Newton’s orbit whom he takes on as housekeeper and companion.

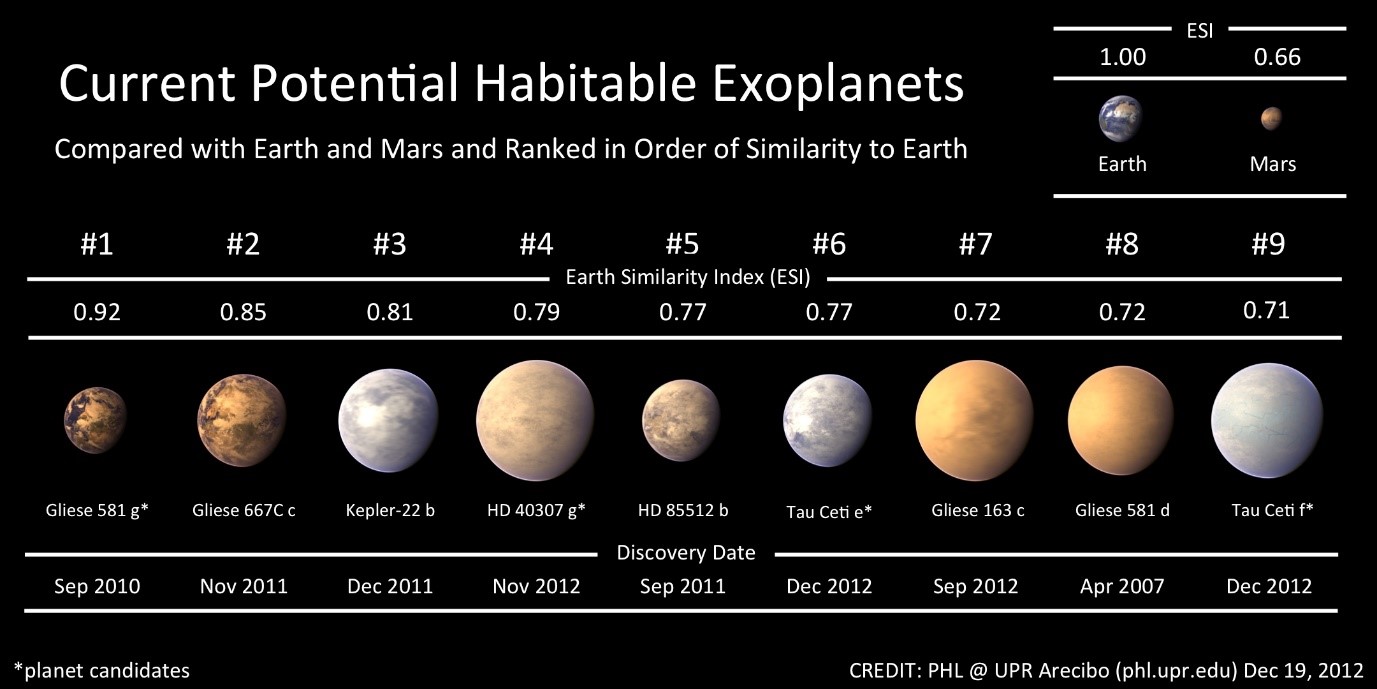

Newton’s home planet is called Anthea; he also makes distinct references to Mars. However, Anthea, with its greater distance from the Sun, longer years, significantly weaker gravity, dry arid surface and year-long journey time to reach Earth would appear to be Mars, or at least as near as makes no difference. There’s a reference on page 191 that an A-level physics student should be able to use to calculate Anthea’s orbit (250 million kilometres from the Sun as it happens), near enough to Mars (226 million kilometres) to say if it walks like Mars and quacks like Mars – it’s Mars!

Newton’s knowledge of our world comes entirely from television, not unreasonably because our radio and TV broadcasts have been travelling out from Earth at the speed of light since Marconi sent his first wireless signal. Just over a hundred years ago, the planet earth burst into radio luminescence with an increasingly bright squawking babble whose ripples have now spread out 100 light years from our otherwise nondescript solar system. A civilisation with sensitive enough radio telescopes could have been listening to our soap operas for decades. There are reportedly 100 habitable planets orbiting stars within 30 light years – that could have just about picked up coverage of the fall of the Berlin Wall (and other more recent events). What other speculative fiction might be inspired by what our near neighbours may – by now – have heard of us?

Newton’s Anthea, lying within just a few light-minutes of Earth, would be much more reliably up to date, but Tevis amuses us with the bafflingly distorted view of humanity that an alien would get from TV. There are other writers who have used that theme of “what would they think of us if all they saw was TV” – for example, the splendidly amusing Galaxy Quest where the late lamented Alan Rickman dons the garb and persona of space-elf that so many science fiction stories seem to love.

Newton describes himself at one point as an elf:

“Elves have the power of adapting themselves to extraordinarily difficult environments such as this one.” He waved a shaky hand out towards the lake. “I am an elf.”

The first space elf, perhaps – predating even Spock. Newton shares those fundamental Tolkien characteristics of aloof, tall, long-lived, gifted and benign beings acting as patrons of the human race. Newton struggles at times to come to terms with the reality of humanity – worse even than its TV!

“…suddenly he felt disgusted, weary of … this aggregate of clever, itchy, self-absorbed apes – vulgar, uncaring, while their flimsy civilisation was, like London Bridge and all bridges, falling down, falling down.”

Newton’s burst of ennui with the home he has fallen into, a projection surely of the writer’s own feelings, has a certain resonance now fifty-five years after the book was written. It is a timely reminder that even the past was not perfect, and the problems of the present stem from within each of us as much as from without.

Tevis wrote in a time of growing nuclear proliferation and Cold War tension. He has Newton set himself a time limit based on the certainty that the Earth is crashing towards an inevitable doom and – paradoxically – his own kind’s salvation may be the Earth’s too. For Anthea is a ruined world, turned into a desert by its inhabitants’ foolishness, though it is nuclear war driving an environmental disaster that has reduced the number of Antheans to barely enough to hold a Spartan mountain pass.

Tevis gifts Newton a mission, a coherent spine to the story – a mission he was selected and trained for. This gives the book a sense of direction and purpose, even as Newton himself drifts into doubt and drink, wondering if either Earth or Anthea can be saved from themselves, or even deserve to be saved. Reflecting on his introduction to and growing abuse of alcohol, Newton reflects that

“He did not become drunk in the same way that humans did; or at least he thought he did not. He never wished to become unconscious, or riotously happy, or godlike; he only wanted relief, and he was not certain from what.”

In fact, in his drinking he is perhaps most determinedly human, and certainly like his housekeeper Betty-Jo.

Tevis takes a swipe at religion, too, observing that Betty-Jo and her friends got “drunk on gin and sentimentality” as they sang old hymns of an evening. While Anthea is without such trappings of faith as are seen on Earth, Newton cryptically observes mankind’s manifestation of religious faith is “a thing … which the Antheans in their ancient visits to the planet, were probably to blame for.” Antheans? That’s almost an anagram of Thetans, which would warm the Church of Scientology’s heart!

Newton and Betty-Jo have an affinity for cats – with a touch that reminds me of Terry Pratchett’s DEATH. Tevis writes:

“He looked at it fondly; he had grown to like cats very much. They had a quality that reminded him of Anthea … they hardly seemed to belong to this world either.”

And again,

“He thought, looking at the cat, if only you were the intelligent species on this world. And then, smiling wryly, maybe you are.”

For anyone who has ever owned a cat, the idea that they might be intelligent aliens is deliciously enticing, more so even than Douglas Adams’ dolphins and the aquabatics with which they tried to say “so long, and thanks for all the fish.”

Newton watches films and TV constantly – his lawyer Farnsworth takes care of the business empire founded on his technological innovations. The man/alien himself is left with too much time on his hands to think and drink and reflect dourly on what diet of propaganda he is being fed.

“These films seemed … more and more wildly chauvinistic – more committed than ever to the fantastic lie that America was a nation of God-fearing small towns, efficient cities, healthy farmers, kindly doctors, bemused housewives, philanthropic millionaires.”

I wonder if the lie has changed that much in the half century since it was written?

Newton’s fall to earth is not merely a physical one, but a psychological one as he finds himself drawn ever further into human doubt and despair, dependent on the companionship of Betty-Jo and the confidence of Nathan Bryce. Bryce suspects Newton of being alien, yet has little idea of what he would do if he could prove it.

Ultimately, though, the challenge to whether Newton will succeed in his mission comes from without the alien, rather than from within him. It is a crisp, well-told story that still feels fresh and in some ways powerfully prescient.

The film (directed by Nicholas Roeg and starring David Bowie, 1976)

The film (directed by Nicholas Roeg and starring David Bowie, 1976)

The film was produced a decade after the book, a different time with different tensions. However, Roeg is more faithful to its source material than many other adaptations (I might mention I am Legend; I might mention Blade Runner.) The same characters exist in substantially the same roles

Betty-Jo was renamed Mary-Lou – I suspect to reflect the fact that the character was younger and the film later in an era when 20-somethings were unlikely to be called Betty-anything.

Oliver Farnsworth the lawyer is given a partner, Trevor, in a very simply presented gay relationship that reminded me of Miguel and Diago in Teresa Frohock’s Los Nefilim trilogy. There was a line of specific abuse where one character calls Farnsworth a faggot, which I remember from my first viewing of the film but which seems to have been culled from the 40th anniversary edition that I bought from Amazon. That aside, Farnsworth and his partner are portrayed simply as a couple who happen to be the same sex and whose affection for each other is shown in small acts of tenderness and care, rather than extravagant bedroom scenes. Though perhaps, given what the film shows of other characters’ love lives, that focus on the platonic for the gay characters is discriminatory.

There are reasons why the film was given an X certificate when first released. Tiny lines of allusion in the book are developed into extended nude scenes.

In the book, Bryce discovers the strange new photographic film that Newton’s corporation produces when he notices it in a chemist shop. In the film, he discovers it when his current student lover brings out a camera to take pictures during their lengthy love making while he takes a break from marking her term papers.

While the book made a reference simply to Bryce not wanting to “talk about himself, his fear, his cheap lust, his dreadful and foolish life”, the film shows us a sequence of identical bedroom scenes with interchangeable eighteen-year-old students all somewhat dubiously insisting the 40-something Bryce is nothing like their fathers.

In the book, Betty-Jo buys herself some nice clothes and underwear in anticipation of sharing more intimacy than a bottle of gin with Newton – but it comes to nothing. In the film – in the parts that were new to my memory – one sees an awful lot more of both Newton and Mary-Lou than would have been anticipated from the book.

There is also a line in the book where Newton reflects: “And he wanted his wife. With the dim Anthean body sexuality – a quiet, insistent aching.” While I had no idea what Anthean body sexuality might mean (and am grateful that Tevis chose not to enlighten me) Roeg took that line and extrapolated it into Newton remembering and visualising a session of watery gymnastic dance that had the lovers looking like a pair of drenched contestants in the final water cannon contest of I’m a Celebrity Get Me Out of Here.

The film’s plot deviates from the book also. Tevis gave Newton a logical plan to save the remaining people of Anthea from their past and to save the people of Earth from their future. Roeg never makes clear what Newton’s plan was, though the blurb alludes to some project to take water from the oversupplied Earth back to the arid world of Anthea – an idea that strained my suspension of disbelief given how much energy is expended getting even a small satellite into orbit.

Tevis made the story about the survival of Newton’s people, Roeg makes it more personal, about the survival of Newton’s Anthean family, a nuclear unit of mother and two children that we glimpse in progressively deepening desperation as they wander their desertified world in grey body suits.

The audience for film and book are necessarily different. Roeg is true to much of Tevis’s work, but he stretches the original envelope of the story in places. The final conflict that faces Newton, even the true nature of the people who oppose him, is never really revealed in the film except in a briefly glimpsed photograph that hints at a key antagonist’s past. Instead, we get an extended look into Newton’s period in a gilded cage and an uncomfortable (for me) development of the romance between him and Mary-Lou, a theme which I never saw in the book.

Ironically perhaps, where Tevis had a subtext on a grand scale of the entwined fate of two worlds, on the larger scale of the cinema screen, Roeg instead chooses to focus on something smaller and more intimate – the people and their relationships.

No matter what, though, the film is carried by Bowie’s performance, brilliantly cast as the outsider, the alien. From his opening scene, walking awkwardly down the side of a gravel hill, Bowie captures the strangeness and the fragility of Newton. Throughout, with his pale, stick-thin body, his crystal English accent, his fierce gaze, Bowie exudes the contrast of intellectual power and physical frailty which makes us fear for him and yet fearful of him.

All around him, others show the passage of time in greying temples, receding hairlines and makeup to thicken youthful cheeks into flabby middle age. But Newton/Bowie alone remains unchanged – the eternal youthful space elf – maybe he wasn’t acting at all!

In one report, Bowie said he remembered little of the production because he did the entire film on 10 grams of cocaine a day while falling apart inside. His co-star, Candy Clark, who played Mary-Lou, said he was the perfect clean professional throughout.

Watching his remarkable depiction of Newton, both stories appear equally plausible.