Self-Publishing And The Proliferation of Subgenres

There’s an understanding in the television industry today that there will never be another Cheers, in that that there will never be a show that regularly pulls in 20 million viewers a week. By way of comparison, the highest rated show this week pulled in a paltry 4.5 million views, and, interestingly enough, both Firefly and Arrested Development were canceled for pulling in 4.7 and 4 million fifteen years ago.

In a nutshell, there’s no longer a show everyone tunes in for. Yet total TV audiences have not decreased over the years. Instead, they have splintered.

The reason Cheers was so popular wasn’t the quality of the show; rather that there were only four networks available at the time. There were few other choices, as demonstrated by how TV audiences fragmented once cable and then streaming services appeared. Because with the birth of these new channels came new shows to fill them, shows tailor-made for the very specific audiences bearing their brand in their names: Disney, Entertainment & Sports Programming Network, Home and Garden, Arts & Entertainment, etc.

In effect, each new channel created its own specific brand of what audiences knew they could expect when they tuned in. And as these more esoteric and specifically focused shows took hold, they siphoned off the viewers of the broad audience appeal of shows like Cheers.

The same pattern of migration from the broad genres to the specific subgenres can be seen in fantasy and publishing in general: gone is the catch-all high fantasy epic like Lord of the Rings in favor of more niche books in their respective subgenres. And this migration is exacerbated, if not entirely fueled by, self-publishing.

While many authors write for the joy (some might say “compulsion”) of it, traditional publishers are a business. It’s their job to make money, which is why they’re so conservative in their decisions, just like the film and television industry, which abides by the adage “the same but different.” Production companies, just like publishers, know audiences constantly crave something new to consume. But they’re also terribly averse to losing money, so they want to cleave close to already-proven products. Hence “the same but different,” which boils down to “tell me what movie it’s like and then tell me the one thing that slightly differentiates it enough to make it feel new.”

That‘s why we get so many movies that are “It’s Die Hard but in an X” where the X is an interchangeable location. Or maybe, when they’re being extra creative, perhaps a different gender or skin tone for the protagonist.

Top Five Worst Die Hard Rip-Offs

The same idea holds true for the publishing industry, and we can’t fault these businesses for making these logical decisions. It’s quite the monetary investment to publish a new book by an unproven author, just as it is to create a new show from scratch from anyone but a proven showrunner. It’s the company that’s fronting the startup money, and the same company that’s going to eat the cost if the book/show turns out to flop. And, unfortunately, for every hit you get there’s going to be at least five flops. This is why publishers and producers favor a conservative portfolio consisting of very similar stories: They have a proven commodity, so why mess with what’s not broke?

However, this incessant insistence on the familiar weeds out a lot of uniqueness that deviates a bit too much to what’s come before. As Dyrk Ashton, Sigil Independent guild member and enemy of commas everywhere, commented on his choice to go self-published: “I did quite a bit of research into both trad and self-publishing for Paternus, including talking to author friends of mine and asking them to read it. The consensus was self-pub because I wanted to experiment with tense, POV, pacing, and even punctuation in a way editors would most certainly want to change.”

However, this incessant insistence on the familiar weeds out a lot of uniqueness that deviates a bit too much to what’s come before. As Dyrk Ashton, Sigil Independent guild member and enemy of commas everywhere, commented on his choice to go self-published: “I did quite a bit of research into both trad and self-publishing for Paternus, including talking to author friends of mine and asking them to read it. The consensus was self-pub because I wanted to experiment with tense, POV, pacing, and even punctuation in a way editors would most certainly want to change.”

It’s publishers’ jobs to keep their books as accessible to the widest possible audience, which is why epic fantasy ruled the roost for so long: by buying mostly epic fantasy for so long, it proved audiences obviously only wanted epic fantasy. And this worked fine when there were only the “Big Five” publishers, just as it did when there were only four networks, but the birth of self-publishing, like the sudden influx of cable channels, has changed the playing field. Before the internet, a fantasy fan could only find books in the (maybe) half aisle assigned to it in the bookstore (usually sharing room with sci-fi), which were broad, already proven commodities.

Yet now a quick google search can yield any interest, no matter how esoteric or odd, in a matter of nanoseconds.

With the internet available, authors no longer needed the infrastructure traditional publishers and bookstores provided, and could connect directly with audiences without going through the traditional gatekeepers. As such, authors wrote the books they always wanted to write, knowing they could find the niche audience out there that wanted exactly the same thing they did when writing it. Timandra Whitecastle summed it up pretty well: “I have a passion for epic fantasy tales, so I’m writing one because I couldn’t find the kind of hard-boiled, European flavored, action heavy, strong female, character driven book I wanted to read.” Authors like her and other Sigil Independent members were no longer just bypassing the gatekeepers at the agent/publisher level, but the buyers at the bookstores as well.

In effect, just like the creation of new and specifically targeted cable channels, this influx of direct connection with audiences created the same fragmentation of the fantasy genre when fans sought out their own specific interests in the form of rapidly evolving subgenres.

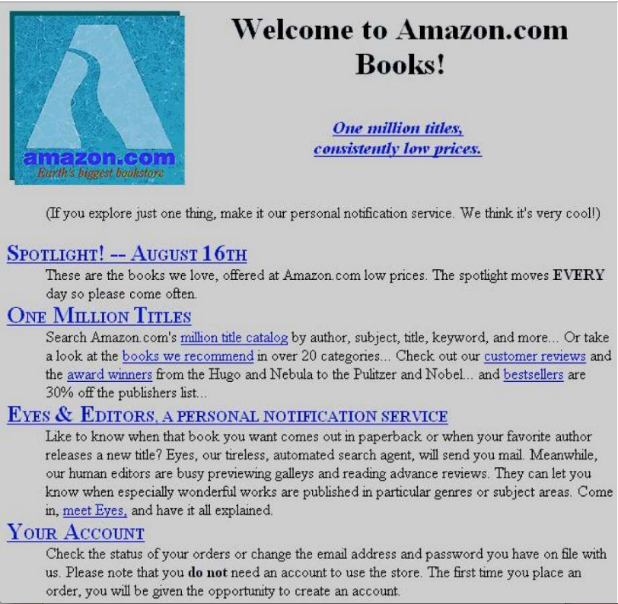

Don’t believe me? Check out the original Amazon page from when it launched in 2000:

It brags of a whole “20 categories,” which encompasses ALL its genres, from history to hantasy. Compare that to today when there are 23 subgenres listed on Amazon within the fantasy genre alone. Fantasy Book Review lists 30, and Best Fantasy Books lists 76.

To use Wikipedia as our authoritative standard as to the genre’s evolution (and why shouldn’t we, since college kids the world over use it for their term papers?), fantasy aimed at adults came into existence in the form of Lord of the Rings in 1954 (as opposed to aimed at children as in The Hobbit from 1937), which marked a tectonic shift in the fantasy genre as a whole. In effect, it bifurcated the genre, creating the first two subgenres: fantasy for adults and fantasy aimed at children.

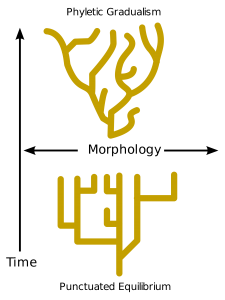

Such a basic division probably seems ludicrous to fantasy fans now, but it’s not until Terry Brooks’ 1977 Sword of Shannara that fantasy hit the mainstream, at which point the genre begins to evolve again. The next phase of subgenres doesn’t begin to crop up until the 1980s, which is about 40 years since Tolkien put out The Hobbit, and about 100 years since the first seeds of fantasy in the Victorian era. So, in effect, until the early 1990s, a few subgenres were being born every 20 years on average.

Yet in the last ten years, somehow another 50+ subgenres came into being, which just so happens to coincide with the creation of easy self-publishing. In biological terms, this is known as punctuated equilibrium when “evolutionary development is marked by isolated episodes of rapid specification between long periods of little or no change.”

To invoke the evolutionary metaphor a bit more, self-publishers are the agile mammals rushing to fit the evolutionary niches overlooked by the lumbering dinosaurs. Spend a few hours in self-publishing online circles, you’ll hear the term “writing to market” bandied about, which boils down to giving audiences the exact esoteric trend they want at that exact moment. As such, successful self-publishers watch trends like hawks, tailoring their output to where they see audiences gravitating. This allows self-publishers to ride the wave of what’s currently cresting rather than reacting to the trend after the fact. Hence the sudden rise of subgenres like military sci-fi or dragon-shifter paranormal romances.

In effect, if you have a particular audience itch, there’s some self-published author who’s willing to scratch it. Usually for under $5.00.

Despite the tone of this article (and mention of lumbering dinosaurs and agile mammals), it is not meant as another trad vs self-published rant. Instead, it is meant to highlight the inherent differences in what each type of publisher wants. As a business made up of dozens to hundreds of individuals, traditional publishers seek books with the largest possible audiences. They need massive hits to support their infrastructure, so they seek out the broadest group possible. Self-published, on the other hand, consists of individual authors seeking out others with similar specific interests. This is not to say that self-publishers don’t want that universal, break-out hit; rather that they can survive off a much smaller, niche in-group.

And with the current ease of self-publishing and influx of new authors, you can expect the fantasy genre to swell with new subgenres by the day.