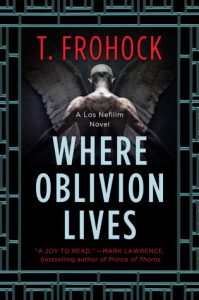

Where Oblivion Lives by T. Frohock (Book Review)

Where Oblivion Lives takes us once more into Frohock’s world of Los Nefilim – a fantasy creation overlaid on historical reality as intrinsically and indivisibly as the hologram in a modern banknote.

Where Oblivion Lives takes us once more into Frohock’s world of Los Nefilim – a fantasy creation overlaid on historical reality as intrinsically and indivisibly as the hologram in a modern banknote.

This volume in the tale of Diago, Miquel and their son Rafael is written as a standalone; there is no need to have read the previous trilogy of Los Nefilim novellas in order to decipher the plot. However, those of us already familiar with the nuclear family and their community of like-minded souls have something of a head start in acclimatising to the world Frohock has insinuated between the pages of history.

This is fantasy, so there is magic. Frohock’s magic is triggered by music, sigils of power traced in the air and then armed with a song or a note, an inspiration drawn from the resonances of Gregorian chants. When the story opens, Diago is being tortured at a distance by the music of a stradivarius he once owned, but must also work on a musical key that is key to so much more for the Nefilim leader he serves.

Diago has come to work for Guillermo and the Spanish branch of Los Nefilim as the Iberian peninsular teeters on the brink of Civil War. The Nefilim live and work in the world of mortals, but are servants of higher powers: the angels, powerful by the standards of men, but mere foot soldiers – an Inner Guard – in the service of the Thrones and their wars with Daimons and even each other. The Nefilim live long lives free from disease and blessed with swift healing, but immortality does not protect their physical bodies from death or deformity. Diago has lived lives before the one in which we meet him and he has known his Nefilim compatriots before fighting with and even against them in previous incarnations.

As Diago reflects, “It’s our memories that make us old,” but the memories of a Nefilim are a tapestry of many threads, with the recollections of previous lives lying dormant until rekindled by some present association. So Frohock manages to give us two stories: the past medieval encounter where Diago last died and the present 1930s travails in which he faces death again.

Having spent much of his current life as a rogue Nefilim – unaffiliated, a freelancer – Diago feels compelled to prove his worth. He has a need to earn the trust of his husband Miquel’s colleagues within the Spanish Inner Guard, and to establish a safe home in the closed Los Nefilim community of Santuari where his young son Rafael can live and grow and enjoy his futbol. That drive, and circumstances, conspire to split the family halfway across Europe and to put Diago, his family and his fellow Nefilim all in great peril. The story builds momentum like a piece of music as the various threads converge on a Gotterdammerung crescendo.

At times the story reminded me of John le Carre’s Smiley’s People, with Diago embroiled in clandestine operations across a landscape of safe houses and entwined intelligence communities. But Diago’s path leads him towards a great country house which echoes with resonances from the doomed House of Usher or even Thornfield Hall where mystery and danger from the past stalked the lives of Jane Eyre and Mr Rochester.

For all their power and magic and immortality, Frohock’s heroes are propelled by ordinary human drives of love and family. Diago and Guillermo are both fiercely protective of their respective children Rafael and Ysabel, aged just 6 and 8. Frohock conveys both the innocent curiosity of youth along with the fact that these are no ordinary children. They are immortals in their own firstborn lives taking their first steps towards their fathers’ battles.

Those who have followed Frohock on social media will know the store she sets by research that is not simply careful, but utterly meticulous. This is an author whose first query on the recently released “Mary Queen of Scots” was – “Why does she speak with a Scottish accent?” as the film failed its first test to accurately depict the speech of a young woman who had spent her entire childhood in France.

So, when I read within Where oblivion Lives of a person named Ernst Issberner-Haldane a member of the Ordo Novi Templi, I made myself a note: “What’s the betting this is a real person?” Google soon confirmed my suspicion, albeit with an entry in a language I could not read. Later, again, a brand of pistol – the Beholla – turns out to be authentic both to the period and to the provenance that brings it into one character’s hand. There is something reassuring in that depth of research, in knowing that the story is not just overlaid but totally embedded in the real history of the period. It is a care for the work that also supports the reader, much as Peter Jackson’s attention to detail meant the hobbits always had furry feet, even when their feet were not in shot, and even at the cost of hours in makeup.

Frohock allies her detailed research with a lyrical turn of phrase:

“In the morning,” George murmurs. He has no desire to leave the bed to go wandering through a night made brittle with cold.

Or a delightfully sharp exchange which again shows Diago’s commitment to his husband, the deep family thread that binds the story and its characters together.

“Pity. I’ve never had the occasion to seduce one of the daimon-born.”

“You don’t have one now.” He picked up his glass with his left hand so she would see his wedding band.

“I thought that was for show.”

“It is. It shows you I’m married.”

The Holocaust still lies ahead of Diago; Hitler is not even Chancellor yet, but ripples of that dark future can still be felt as Diago picks his way through south west Germany. Frohock’s observation on the nature of monsters – the ordinariness in which total inhumanity cloaks itself – seems apt to all ages.

Nothing sinister marked his features, but then again monsters generally moved through the world unobtrusively, camouflaged by banality until the deeds manifested in the form of dead bodies or broken souls.

Frohock’s stories challenge normal categorisation – you might think Where Oblivion Lives a kind of urban fantasy perhaps, but set firmly in a historic context. But this is no piping Spanish Twilight. Frohock depicts a richly imagined world, diverse in every way, where fallen angels and rising daimons haunt a world half ruined by one great war and trembling on the threshold of another.