The Migration by Helen Marshall (Book Review)

There are aspects of Helen Marshall’s debut that feel like a young adult work – a young female protagonist in a collapsing contemporary society haunted by family woes and with an ephemeral promise of romance. However, in the skilled yet accessible writing and the poetic themes the author explores, The Migration reads more like literary fiction. Helen Marshall is an accomplished writer who has cut her teeth on award-winning short stories. It is no surprise then that this thought-provoking and enjoyable story does not feel like a first novel.

There are aspects of Helen Marshall’s debut that feel like a young adult work – a young female protagonist in a collapsing contemporary society haunted by family woes and with an ephemeral promise of romance. However, in the skilled yet accessible writing and the poetic themes the author explores, The Migration reads more like literary fiction. Helen Marshall is an accomplished writer who has cut her teeth on award-winning short stories. It is no surprise then that this thought-provoking and enjoyable story does not feel like a first novel.

I didn’t read the blurb before I started this book, and I am glad that I didn’t. There are a few small spoilers within it that I am glad I didn’t know before I came across them in the text. It is perhaps significant that one of the back cover comments is from M.R. Carey, author of The Girl With All the Gifts, for there is another story best read from totally cold to allow its plot reveals every bit of freshness they deserve.

In the same way, this is a difficult review to write because some of the images from nature that The Migration conjured in my mind are themselves too big a giveaway to mention here. Suffice to say the setting spans crises on a global and an individual scale.

The long-heralded fruits of climate change are being felt the world over, while a strange disease has arisen that afflicts only the young. These disasters are brought into sharp relief through the eyes of Sophie Perella. Not just threatened with flood inundation in the riverside cottage she now calls home, and not merely fearful for her sister Kira, one of the first to be diagnosed, but also afflicted by the transatlantic displacement from her native Canada to her aunt’s house in Oxford.

Having dragged two daughters across a narrower span of sea from Kent to Belfast, I have seen at close hand the challenges that sets for adolescent social integration. Sophie experiences that same disconnection from the support networks of her friends, the difficulties of finding a way to study in an entirely different education system, of finding a way to pick up the threads of her own future.

These dilemmas are given added urgency with the challenge of Kira’s sickness. Marshall gives her invented plague a certain strangeness of symptoms. Sufferers are afflicted by sleepiness and loss of focus – occasional absences of attention – the petit mal, yet with some aspects of haemophilia. It presents as a subtle illness that defies diagnosis except by a formal test and whose progression is at first unknown, unfathomable. This is not the plague of other apocalyptic stories, with sweats and fevers, buboes and messy death.

Marshall herself spent time as an Oxford-based post-doctoral researcher into the literature around the time of the Black Death. This experience informs the character of Sophie’s aunt, whose research into old plagues puts her in demand as scientists battle to understand this new pandemic. As she and Sophie work together, it seems the past may have something to tell them and that there may be a link between an illness that impairs the judgement of the young, and the inundation threatening to flood the world.

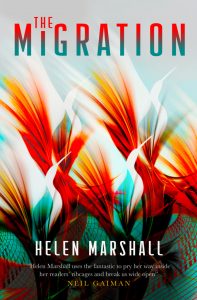

I have to say that I love Julia Lloyd’s cover for the UK version of the book. It captures the strangeness of the story to my eye, hints of shapes, glimpses of patterns, a touch of science, that become easier to appreciate as you read on and the story develops. To say more would probably be too spoilerish, but I have rarely found a cover so seemingly abstract, yet which resonated so well with the unfolding story it introduced.

Despite the global crises, Marshall’s story remains tightly focussed on its first-person protagonist Sophie and her response to the various challenges and traumas she encounters. Sophie finds allies in strange places, from dark hospital corridors to college greens beneath the shadow of dreaming spires. There are the familiar teenage themes of parties and staying out late and alarming the adults, but all against the backdrop of a strange unquantifiable danger that haunts the young people of The Migration.

The adults, however, are the ones who struggle more with how climate and disease are changing the realities of their world. Scientists seek not so much to understand as to control the development of the disease, their medical intervention as unsubtle and ultimately ineffective as the sand bags that are dumped in cottage doorways to stave off the rising floods. Without ever quite tipping over into the mayhem of a zombie apocalypse story, Marshall still conveys a sense of a society that is fragmenting under pressure and in the process badly losing its moral compass.

Sophie is let down by both her parents – each retreating in different ways from facing the mysterious illness that has gripped Kira. Sophie is the one left sharing a room, secrets, fears with Kira, and ultimately Sophie is the one seeking to preserve some kind of future for her sister in a moment of impulsiveness that fundamentally changes the story’s direction.

Death stalks the story, from its opening line to its closing page. Throughout, Sophie struggles to come to terms with the way the horizons of her family and her generation are being brutally curtailed by illness and government, striving for meaning and purpose in the seemingly senseless.

Marshall’s prose is fresh, simple, yet also powerful.

“I tie knots in my memories, make a rope out of them to keep me sane. When I wake up there are those precious pockets of time when I forget what happened.”

Sophie is a protagonist for whom we quickly care and fear, a heroine for whom we want the best – but it is in the nature of Marshall’s inventive story that we are surprised by the final outcome that we end up hoping for, for Sophie.