Interview with Lewis Shiner (OUTSIDE THE GATES OF EDEN)

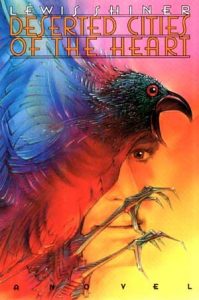

Lewis Shiner was involved in the birth of the cyberpunk scene with his debut novel Frontera (1984), and had two stories included in the genre-defining anthology Mirrorshades (1984) edited by Bruce Sterling. Since then he has refused to be nailed down to a single genre, writing such varied works as the magical realist Deserted Cities Of The Heart (1988), the World Fantasy Award-winning Glimpses (1993) and literary fiction novels like Dark Tangos (2011) and Black And White (2008). His latest novel, Outside The Gates Of Eden, is a lyrical exploration of the idealism of the sixties, how it tied into the popular music and politics of the day, and how it’s since disappeared. Lewis Shiner was kind enough to talk with The Fantasy Hive via Skype, to discuss his new novel and his incredible career.

Lewis Shiner was involved in the birth of the cyberpunk scene with his debut novel Frontera (1984), and had two stories included in the genre-defining anthology Mirrorshades (1984) edited by Bruce Sterling. Since then he has refused to be nailed down to a single genre, writing such varied works as the magical realist Deserted Cities Of The Heart (1988), the World Fantasy Award-winning Glimpses (1993) and literary fiction novels like Dark Tangos (2011) and Black And White (2008). His latest novel, Outside The Gates Of Eden, is a lyrical exploration of the idealism of the sixties, how it tied into the popular music and politics of the day, and how it’s since disappeared. Lewis Shiner was kind enough to talk with The Fantasy Hive via Skype, to discuss his new novel and his incredible career.

Your new novel Outside The Gates Of Eden is coming out with Subterranean Press tomorrow. Would you be able to tell us a bit about it?

Sure. It’s about the 1960s, is the simplest way to talk about it. About the idealism of the sixties and how we got from that luminous point to the dark days that we’re living in now. It uses the music business as a way to focus on all that. There’s really two main characters, who start off in a garage band in 1965, and then kind of go in and out of each other’s lives for the next 50-odd years. One of them becomes a professional musician, and the other one comes from a wealthy family, and he’s constantly struggling between the ties of loyalty to his father and going in to the family business, and his own sixties-inspired need to be artistic and counter-cultural.

You follow the two lead characters through fifty years of history between now and the sixties. What are the challenges of writing and developing characters over that period of time in their lives?

You follow the two lead characters through fifty years of history between now and the sixties. What are the challenges of writing and developing characters over that period of time in their lives?

Well, one thing for sure: I had to take copious notes on birthdays and when various things in their lives happened to keep all that stuff straight. I always have a notebook that I keep when I’m working on a novel, and this one got pretty full just trying to keep the continuity straight. You know, when does this character have a beard and so on. So that’s a lot of it. And also there’s something like seven or eight different viewpoint characters, plus there’s literally dozens of other major supporting characters, and you want each of those characters to have a story arc, so that you know where each character is starting and then they end up somewhere different, and you have an idea of how they got there and why. And juggling that many characters was, well, to tell the truth it was easier than I thought it was going to be! I really thought this was going to be hellacious and I would go off on tangents that I would have to get rid of, but somehow it was like all 880 pages were there in my head and I just had to kind of find them.

Part of the point of the book is how our outlook on the world and politics has changed since the sixties. Was that something you particularly wanted to grapple with in this book?

Yeah, one of the characters is an academic, and her crusade in academia is that somewhere around the 1980s the idea of the hippy became a figure of fun. And everybody was mocking them and the headbands and the peace symbols. And I think her struggle in the book is to reclaim the real value that that period brought: that it’s not in fact morally superior to be ironic than to be idealistic. And that we need that right now.

You’ve written about the sixties and the link between the popular music of the time and the idealism in books before like Glimpses. What is it about the connection?

I think they were mutually reinforcing. I think that the idealism led people to write songs, and then the songs reinforced that idealism, and told other people that it was OK to feel that way, and I think it kind of built up in – an appropriate metaphor here – a feedback loop.

You’ve written about music a lot…

You’ve written about music a lot…

Music has always been really important to me. Like the character Cole in my novel, I was kind of late coming to it. When I was much younger I had the traditional kind of transistor radio. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen one of those objects, but they were about the size of a pack of cigarettes, and would run on a AA battery, and you had the ancestor of the earbud, which was the little earpiece. And everything was mono back then, of course, so you had this one little earplug that you would stick in your ear, and plug into this little cigarette pack-size radio that you carried in your shirt. So I had one of those in the 50s and I was into the Everly Brothers, some of the doo-wop bands of the time, the Tokens, Buddy Holly and all that stuff. Then I kind of drifted off for a while.

Back around age 14 in ’65 I started getting back into rock and roll in a big way. Again, as with Cole in my novel, the thing that really galvanised me was a Bob Dylan concert, which is a big pivotal scene in the early part of the novel. He did his national tour with the Band backing him up, started in ’65, went through ’66. The first half of the show was acoustic, then they had an intermission and he came back with the Band. And in the later stages of the tour this is where everybody was booing and calling him Judas. But when I saw him, the concert that I saw was only the second stop on this tour. He had played Austin the night before and Dallas was literally the second stop with the Band. We all loved it. If there was any booing I don’t remember hearing it at all. And in his book, Levon Helm – who was, of course, the drummer of the Band and was backing him at this point – talked about how the people in Texas were the only people who got what Bob was trying to do. So that was really an amazing experience. And literally the day after I got back from the concert I started pushing my parents that I wanted a guitar for Christmas. I ended up as a drummer, but I had a real conflict inside, whether I wanted to be a writer or a musician. Starting from the Dylan concert and lasting for about ten or fifteen years thereafter. I guess all the way till about 1980 I was still not sure which way I wanted to go. Whether for better or worse, I had even less success as a musician than as a writer! And also by the time I turned 30 it was starting to take a real toll on me, to be up until 3 am playing in grungy biker bars. So I decided if nothing else it would be more comfortable writing rather than to be a musician. And I still clung to that. I have a guitar that I still get down and plunk every once in a while, and I’m certainly a very active listener to music.

Writing about music is one of those things that’s famously hard to do – Zappa likens it to “dancing about architecture”. Do you feel that your experience as a musician informs the way you write about it?

Oh, absolutely. I think that’s really the secret to good music writing – assuming that what I’m doing is good music writing! I think part of the problem with writing about music is that a lot of people who don’t have a lot of technical knowledge about it are just going to go off into rhapsodic poetry, trying to somehow recapture what music feels like to listen to, and I think that’s really dangerous. Whereas if you can write about it with a little bit of technical expertise, then you can talk about key changes and arpeggios and stuff like that. I don’t think that necessarily makes it inaccessible to people who aren’t super knowledgeable about music, but it helps present it more from the way a musician sees it rather than how a fan sees it. And I think that’s what I look for in good music writing: something that gives me a real insight as to what’s going on with the musicians that are playing.

I’m guessing a lot of research went into the book?

If I was searching for a single word to describe the research, I would describe it as constant. It was one of those things where I read dozens of books, if not in their entirety then certainly in large parts. And, you know, thank God for the internet! I could not have written this book without the internet. It seemed like once or twice a page I’d have to look something up. And I was trying to be really scrupulous about not using any slang that was inappropriate, so I was constantly turning to slang dictionaries and a few websites I found. There was this one that was a surfing website that talked about surfing vocabulary in the 1960s, stuff like that; looking up where various artists were at a particular time; going back to the liner notes in my CD collection; just constant, constant research. And for me, that was part of the attraction. When I first conceived of the book, one of the things that made me want to write it was, well, this will give me an excuse to do a lot of research. And it certainly did! But I love research, and I think that, in the books I admire, it’s the ones where you can really tell somebody’s done their research that have impressed me. And I think the way to tell that is how often it surprises you. Because if you’re not doing your research, you’re relying generally on hand-me-down clichés, but when you’ve really done your research, you find all this surprising stuff that gives it a real impact.

Thinking about some of your other books, Glimpses won the World Fantasy Award in 1994….

Thinking about some of your other books, Glimpses won the World Fantasy Award in 1994….

I would say that the main difference between Outside The Gates Of Eden and Glimpses is that Glimpses is really a fan’s book. It’s the ultimate incarnation of fandom where this guy has the ability to recreate lost record albums. I think one of the definitions of fantasy, and science fiction too, is taking the metaphor and actually literalising it. And you see that in Glimpses, where people who are rabid fans of the Beach Boys for example, feel this closeness to the musicians, as if they actually knew the musician personally. And I think what Glimpses does is to make that literal. Ray is trying to conjure up these albums in his head; eventually, he not only conjures up the music, but he time travels to become friends with – or at least have a personal relationship with – these musicians that he cares so much about. So that’s really the fan’s experience rather than the musician’s experience.

The book I wrote after Glimpses [Say Goodbye: The Laurie Moss Story, 1999] was also a musician’s book. In some ways, I suppose it covers a little bit of the same ground as Outside The Gates Of Eden, but it’s about a young woman trying to make it in LA in the nineties, which is kind of a different thing than the sixties. But several of the characters from Say Goodbye also show up in Outside The Gates Of Eden.

For writing Say Goodbye, did that involve similar amounts of research but into the music of the nineties?

Somewhat, yeah. There was College Music Journal, CMJ, which was this magazine aimed at the university DJs who were working, like student radio. And every month they’d have a CD with selections of the hip new music, and they’d have articles about the venues where people played. That was really useful to me. So when I got this band on tour across the US, I was able to get some club names and descriptions from these CMJ magazines. However, I will say at one point I couldn’t find anything. I was having them play I think outside of Baltimore, and so I said ‘what the heck’ and I instead used a club that I knew of in Houston. So I just sort of plugged that in there, and made it up, and then I got a fan letter saying, “I’ve been to that club in Baltimore, that was so cool the way you described it.” That was a piece of luck! And again, yeah, lots of research on the apartment Laurie is staying in in LA, on Sunshine Terrace – George R. R. Martin of Game Of Thrones fame was actually living in that apartment for a long time, when he was doing various Hollywood projects. And he actually loaned me the apartment for a couple of weeks when I was out there doing research on Glimpses. So I was able to describe that apartment and the neighbourhood. You work in as much of your own experience as you can.

One of the lost records that Ray goes back and rescues in Glimpses is The Beach Boys’ Smile, but of course since the book was written we have the version of Smile that Brian Wilson finally recorded and released as an official album.

Yep, and a great record it is. I was, first of all, very very pleased to actually see the record, and I was pleased at how good it was. And a little surprised; it was a little more intellectual than I had thought it would be. I thought it would be much more of an emotional record, but it’s actually kind of a left brain record. It’s still great, I was really glad to see it, and I was happy for Brian – he’d been carrying the weight of that album around with him for his entire life, and he was actually able to complete that. On the other hand, I thought, well, there goes the movie of Glimpses! You know I still get fans asking me, isn’t anybody going to film Glimpses? But history has made that redundant at this point. It would be a tough sell in Hollywood.

You were talking about George R. R. Martin, you wrote in his Wild Card series…

I did indeed. That was back in the eighties, and I was involved in the very early days of that project. And it’s not something I’ve kept up with, I have to say. It was fun at the time, and I enjoyed it, and of course as George’s career has exploded, it’s been a great source of steady income. And George is just a terrific guy. And I need to go on record here as saying that, because he comes from a working class background, he’s very much a labour union type guy, and all his wealth and fame has not changed that at all. And he’s really supportive of his friends, and he uses his current popularity to help friends of his, including me. I’ve got to be giving him credit for that.

In the eighties you were also involved in the cyberpunk scene with your debut novel Frontera and the stories you have in Mirrorshades…

In the eighties you were also involved in the cyberpunk scene with your debut novel Frontera and the stories you have in Mirrorshades…

Yeah, and by the way, I really appreciate the review you did of Frontera. You showed me some stuff in there that I was not all that conscious of, and made me feel better about the book actually than I had in some time. Yeah, I kind of fell into that. At the time, I was living in Austin but I was very much into the whole private eye scene. I was reading a lot of private eye novels, and had written one, was working, and I had a series of short stories featuring a recurring character. And I was not having any real success with that, but that was where my energy was. I was part of the Turkey City writers group down there, but I wasn’t turning in science fiction stories. I would turn in mysteries, and I was also getting a little interested in the horror genre which was kind of taking off then, Stephen King and people like that. And then Bruce Sterling had gotten to know Bill Gibson, I guess they were penpals, and we had a Turkey City workshop that was at my apartment. And he brought along a manuscript of Gibson’s Burning Chrome (1982). And I read that and just went, wow. Suddenly science fiction is interesting again! So I got kinda wrapped up in that for a couple of years. But I can’t ever seem to commit myself to a particular genre or a particular way of writing or anything like that. And after a while, I guess really after Frontera, I just felt like I wanted to do something different. I really don’t have the desire to write the same novel over and over again. Bill has changed considerably over the years, but he’s still got a kind of territory that he’s staked out for himself that he does really really well.

Your work has moved between genres, and by the time you were writing works like Black And White and Dark Tangos, you’d moved quite far away from genre fiction.

Yeah, both Black And White and Dark Tangos owe some of their DNA to suspense fiction. And there’s a whodunnit element to both of those books. But I think what happened was instead of switching from one genre to another, I just started blending them. Black And White is a historical novel, it’s a romance, it’s a suspense novel, it’s a novel of ideas dealing with racism – it’s probably too many genres rather than too specific a genre!

Do you see genre more as a series of toolkits that have useful elements?

Do you see genre more as a series of toolkits that have useful elements?

I think that’s a good way of putting it. Each genre has a certain amount of colours that you can bring to the palette. I’m very good friends with Lisa Tuttle, the brilliant fantasy writer, and she read Outside The Gates Of Eden in manuscript, and she had a really interesting comment on it. She said that had it been a purely mainstream novel, that basically the people would have sat around at the end of it feeling sorry for themselves. Whereas because of my experience writing science fiction, the people are actually tackling the problems and trying to solve them. She felt that was a kind of bleedthrough from the SF genre into the mainstream novel. And I really like that idea. I like the thought that my dabbling in these various areas was not just a waste of time and not frivolous but that I maybe gained a little something from working with the various other genres. And it was completely unconscious, I wasn’t consciously saying, I wonder how an SF writer would approach this theme. But I guess it was owning up to the fact that there is a part of me that is a science fiction writer that I do bring to the various projects I work on.

One of the things that follows through from the early cyberpunk stuff through to Outside The Gates Of Eden is that you’re a very politically engaged writer.

Yeah, I consider myself a very political writer. There was a dialogue on Facebook a few years ago, where one of the people was saying, “I’m not sure where Shiner is politically,” and I thought, well, man, I’m not sure you’ve been paying much attention! That’s fine, I don’t want to be categorised and dismissed, but yeah, that’s a very important component of the writing to me. I feel like there’s political stuff that I definitely want to talk about. I am not a fan of capitalism, and I think Outside The Gates Of Eden is in some ways a sustained attack on capitalism. And I know my politics aren’t easily categorizable on the scale of capitalist to socialist, but I’m a ‘small s’ socialist, and I have bits and pieces of various sort of left leaning ideologies that are important to me. But on the whole I think it’s a political statement these days to even say ‘do unto others as you would have them do unto you.’ That’s no longer in fashion, it’s political to even say that. And I’ve always been willing to be pretty blatant about my political feelings in my work, it’s an important component of it to me.

You’re involved in the Fiction Liberation Front, whereby you’ve put up your short stories and novels on your website so that people can download and read them.

Yes. That was kind of capitulation to the inevitable I think. And part of it was just not having become a household name, not having my work in every library in the country so people can read it. When it came down to it I just wanted people to be able to read my stories. And it seemed like the most obvious way to tackle that was just to get them up on the web and give them away. I will not be giving away Outside The Gates Of Eden. Maybe that’s not consistent with socialistic beliefs, but until they start giving away food and shelter I don’t feel like I can give everything away. But I am happy to have my backlist up there, and certainly the short stories, cause all my short stories are up and available. Part of the situation is when I first decided to do this and was talking about it with friends and family, the accessibility of digital reading devices was not what it is right now, so if I had a novel up there on the web, people would probably not want to just sit on their chair in front of their computer and work their way through an entire novel. So, it was really kind of a come on to get them to buy the books. And these days, when it’s so easy to read on an iPad or something, that has become less of a revenue engine for me. So it’s just a question really of finding the balance between giving away the stuff that I just want to make sure that people are seeing and trying to get at least a trickle of income.

Having written short stories as well as novels, do you find yourself drawn to one particular form more than the other?

Having written short stories as well as novels, do you find yourself drawn to one particular form more than the other?

Yeah, I think I’m a long form writer. I’ve certainly written a number of short stories, but I’m not a short story reader. I would much rather read novels. And I’m perfectly happy to dig into a 900 page novel myself. And that’s what I like to read, and I think that’s going to be a big influence on what I like to write. I never felt that the short fiction was as good as the long fiction. What really interests me is stuff that can be written on a large canvas. I like to have flashbacks into people’s histories, and a number of different characters and viewpoints that are confronting each other, and so I just feel like a novelistic form is more suited to my taste. And when I get ideas it’s like they come with a word count. So I pretty much know from the moment I get an idea how many pages it’s going to take up to write about it. And I prefer to get the big ideas, because that’s probably going to take more research. It also means that, since I don’t get a lot of ideas, if I get a novel sized idea, that will keep me busy over several years.

So as soon as you had the idea for Outside The Gates Of Eden you knew it was going to be a massive undertaking?

Yeah, immediately. What happened was, I had just read Anna Karenina for the first time, this was about 2010. And I’d read War And Peace three times, but I hadn’t read Anna Karenina. And I thought wow, this is a great book, and he has just captured all the different facets of this particular time in Russia. And I thought, what would Tolstoy write about if he were writing now? Not trying to compare myself here to Tolstoy or anything! But just wondering what would be a Tolstoyian epic theme. And I thought well, the idea of what happened to the sixties, where did that idealism go? And it was like this click in my head. And I grabbed a notebook and started writing stuff down, and within an hour I think I had the basic outline of what the book was going to be. And I had kind of gone back and forth, not consciously, but I had gone back and forth in my books between longer and shorter novels. Frontera was fairly short, and Deserted Cities Of The Heart was a much longer and more complex book. I wrote Slam (1990) which was very quick, then Glimpses which was longer. Say Goodbye was fairly short, Black And White was the longest book thus far, then Dark Tangos was fairly short and compact. I was due to write another big book.

Having become conscious of this pattern and surrendering to it, I said, well, let’s not just write a big book, let’s write a really huge book. And it felt good, it felt right, and I took very few of what I saw as missteps. Readers may feel there’s some missteps in there, but from my point of view I was just really amazed at how everything fell into place for me as I was writing. I always knew the next few pages ahead of me. And I had a couple of temporal land marks that I had laid out, probably about a dozen or so events that I was pretty sure needed to be in there – not all of which in fact ended up in there, but most of those events, those landmarks that I visualised, were there. And so it was just a question of getting from one to the other. There would be times when I was not entirely sure what to do, and I would just go back to that original impetus and say, OK, here’s what we’re talking about, the theme is idealism in the sixties and all that, how do I further that theme with this next scene I’m going to write? That would pretty much show me the way.

So it was a pleasure to write the book in many ways. My day job was not giving me any satisfaction, and this was a great escape for me. I’d come home at night and I had this other world that I could slip in to, and the fact that it took like eight years meant that it was a very comfortable world by the time I was done.

So it was a pleasure to write the book in many ways. My day job was not giving me any satisfaction, and this was a great escape for me. I’d come home at night and I had this other world that I could slip in to, and the fact that it took like eight years meant that it was a very comfortable world by the time I was done.

I suppose one of the things about writing a book that size is that it becomes a significant time commitment.

Yeah, but I like that feeling. One of my best friends is Joe Lansdale, whose work I believe you know. And Joe is not a real patient kind of guy. Joe dives into a book, he writes that book and he moves on. And most of his books are between like 70 and 90,000 words, he doesn’t write the big long epics. And he’s an idea man, he gets five or six a day. He can crank out short stories and novellas on top of the novels like that. He’s like a travelling man. He’s rambling around from place to place. Whereas I like to settle in to one spot and dig in.

What’s next for Lewis Shiner?

Well, that’s a good question. I really put a lot of my heart and soul and everything I had into Outside The Gates Of Eden and I have not written any fiction since then. I finished the book in September of 2017 and have not had the impetus to write any fiction since. I got involved in a blog with a couple of record collector-type guys, and I have been doing some short music articles. There’s a platform called Medium.com, where various people can set up their own online magazines within that platform. We’ve got an online magazine called Tell It Like It Was, and I’ve written a couple of pieces for that, and we’ve published some of my older pieces there. And right now that’s very satisfying to me. I’ve been writing just musical non-fiction. Doing research about the groups, artists from mostly in the sixties, and it lets me do that research that I want to do, and gives me an outlet for some ideas without taking that kind of real major commitment that a novel does.

Thank you very much Lewis Shiner for speaking with us!

OUTSIDE THE GATES OF EDEN, a lyrical exploration of the idealism of the sixties, will be published on May 4th 2019 (US) and August 8th 2019 (UK).