Interview with K.S. Villoso (THE WOLF OF OREN-YARO)

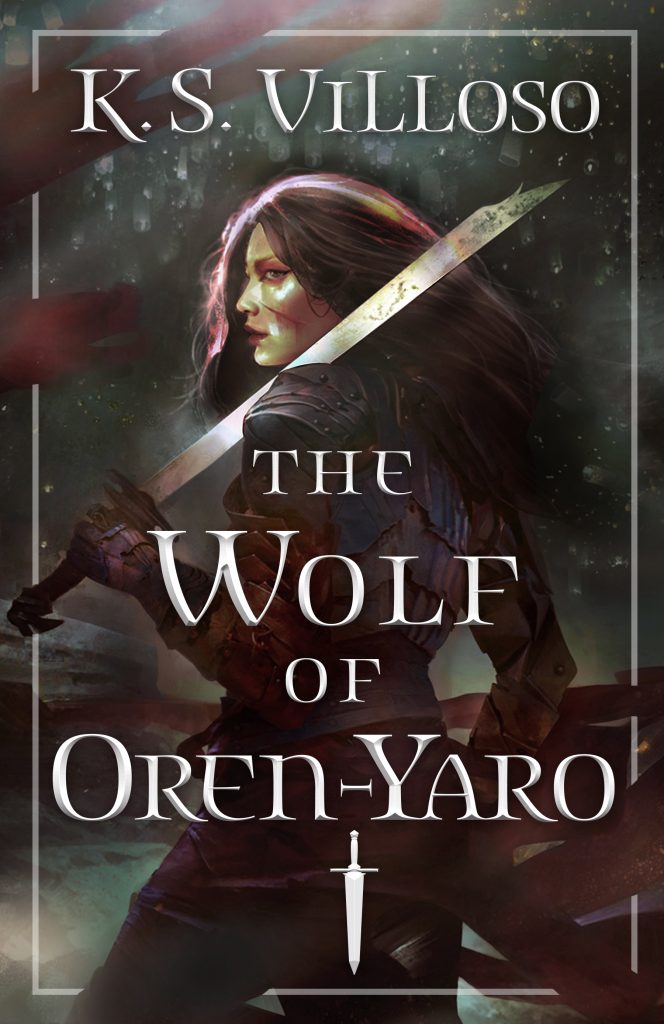

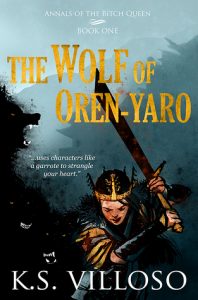

Yesterday, Orbit Books revealed the cover for K.S. Villoso’s THE WOLF OF OREN-YARO. The book (which is awesome, by the way) is already causing quite a stir, and rightly so.

We’re delighted to welcome the author to the Hive today. Now, settle in for an in-depth chat between Kay and self-publishing legend Phil Tucker about the story behind THE WOLF OF OREN-YARO…

Phil Tucker: So, let’s kick things off with your title, The Wolf of Oren-Yaro: Chronicles of the Bitch Queen. It’s clear that you made some very distinct choices when picking it, and were entering right away into conversation with fantasy fandom about women, power, and their portrayals in fiction. Can you share what led you to pick that title and what you were hoping to achieve with the very first impression readers might get of your book?

Kay Villoso: It’s definitely a play on words and perceptions.

I was really interested in dog training for a time, and spent years discussing pedigrees/bloodlines online, so I’ve always had an easier time with the word “bitch,” which we use fairly often. I’ve also been using this word since I was little to mean exactly that: a female dog. It probably also helps that since English isn’t my first language, I didn’t realize this was considered a vulgar term colloquially until later on.

So within the context of the series, people use the title to mean a female wolf, as her family’s crest is the wolf. Why not use “she wolf?” Because “bitch” is the correct term for a female of any member of the dog family. I don’t like to pull my punches when I write; I always go for honesty wherever I can. In a genre that has series titles like “The Gentlemen Bastards,” it technically shouldn’t be a problem.

But it is. It is a loaded word, and the world is not fair when it comes to perceptions of women in power. As someone who has worked in a professional setting, and was raised by a mother who has also worked in a professional setting, it’s amazing the fine line women must tread on a day-to-day basis. You always have to watch how other people perceive you, and not just focus on getting the job done. You need to be nice so people will want to work with you, but also, you need to assert yourself! It’s a ‘damned if you do, damned if you don’t’ scenario.

Fiction is no exception to this. Lots of people jumped into the work with pre-conceived notions of Tali even though her struggles, loneliness, and frustration have been made clear since Chapter One. The power of words is amazing. It’s sort of breaking the fourth wall, in a way…

…because this story, this whole series, is about a person trying to break free from her façade, from what she has been led to believe she “is” to what’s really inside. Note my use of the word “person.” This character is written as a whole person, not a statement; at no point did I write this story thinking “How can I make this book more feminist?” Tali is written with as much depth as any of my characters. Her challenges are the same challenges any of us would face in her position—balancing expectations with desires, trying to shake loose from her father’s shadow, learning to stand on her own two feet.

It’s amazing how the title alone can be enough to create this façade from the get-go. My hope is the contrast between this first impression and what really happens between the pages gives readers a pause. To get them to question their own gut instincts, and empathize. Because in the end, it’s really all about the people within.

Phil: That’s fascinating. There’s a history of oppressed groups taking the epithets that those in power have demeaned them with and claiming them for their own. Would you say that on some level you were trying to do the same thing with The Chronicles of the Bitch Queen? Claim the worst a reader could call your protagonist, and by claiming that term, own it, preventing your readers from using it casually in a way to dismiss Tali, and consequently giving her the necessary space in which to be herself?

Kay: You put that into better words than I could. Definitely. Which is a funny way to look at it considering she is a character in power, but I knew coming in here the challenge in portraying a woman (especially a woman of colour) in her position.

Phil: So tell me a little about the decisions behind Tali’s creation. What led you to want to write her as a character? How did Tali come into being?

Kay: I started planning this story a few years back. I was interested in exploring the Strong Female Character archetype, since the demand for “strong women” was already in full steam at the time. But I wanted to take it a step further—I wanted to see how this sort of character would respond to the same challenges that a male Chosen One character would experience. And then…what if this character had to learn weakness in order to learn true strength? So in my mind, she had to start out already in power—already a Queen, a mother, and a wife, daughter of one of the most powerful warlords in the land. But then I also wanted her to be a real person, to have flaws that prevent her from achieving happiness, and to have desires like most of us. This has resulted in probably the most overwhelming, frustrating, and ultimately intense character I’ve ever written.

Phil: That’s interesting that you wanted specifically to put your protagonist through the same challenges that a male Chosen One would experience. How do you think her being a strong woman as opposed to a strong man resulted in a different tale?

Kay: The most interesting part about this is exploring the perspective of a woman who didn’t have to choose between motherhood and marriage in order to be the hero of her story. She has all these things already; now she has to balance her every decision with her son’s wellbeing, her desire to maintain face while keeping her family whole, and her responsibilities. The stakes, I feel, would be different if she had been male; there would be much of the same search for identity (and in fact, later on in the series, this theme will be reflected with several other characters), but the focus would change.

For example, would a king’s ability to rule be doubted if his queen had walked away from him the same way Tali’s husband did in the beginning of the story? Queen Talyien is feared, but also disrespected; would a ruthless king garner the same response? Stripped off his rank and power, would he be taken advantage of almost immediately? Would he have the same hang-ups about pursuing his own happiness as she does? Obviously everything would still be challenging for him, but would he be as exhausted by the pressures? Most importantly, would he have to make the same sacrifices as she did?

I can’t say for sure. Every character is different. In my Agartes series, I have a mercenary leader whose primary motivation is his daughter, whereas the mother, who had a difficult time accepting her pregnancy and role as a mother, is more absent in her daughter’s life. But I think the narrative has to reflect why these characters make these sort of decisions, how they think and react. Their gender is part of their character makeup, and so it provides more nuance to their decisions and how the world responds to these decisions.

I can’t say for sure. Every character is different. In my Agartes series, I have a mercenary leader whose primary motivation is his daughter, whereas the mother, who had a difficult time accepting her pregnancy and role as a mother, is more absent in her daughter’s life. But I think the narrative has to reflect why these characters make these sort of decisions, how they think and react. Their gender is part of their character makeup, and so it provides more nuance to their decisions and how the world responds to these decisions.

Phil: Did your understanding of what ‘strength’ meant for Tali change over the course of the series? Did she surprise you in how she tackled her challenges, in the decisions she made, and how that reflected her character and her ‘strength’ as it were?

Kay: One of the most surprising things for me over the course of three books is seeing her own voice and perception to events change, even when she remained this strong-willed, force of nature-type woman. Tali from Book One is rigid, abrasive, refusing to bend to outside forces—this is the armour she’s had to wear to survive, what “strength” used to mean for her. But as she sheds her naivete, her rigidity gives way. The story is framed to allow simpler moments of courage and sacrifice to shine through, which Tali begins to notice more as the series progresses.

To be able to support a story like this is one of the things I’ve always appreciated about the epic fantasy genre. Deep inside, we all want to know how we can survive the darkest night before the dawn; this is just one woman’s journey to reach that.

Phil: That’s motivation to read the next two books right there. Book 1 features another wife and royal figure in the mad prince’s wife. Can you talk about her, what her perception of strength might have been, and whether you were purposefully setting her up as a foil for Tali?

Kay: Ah, yes, Zhu. She is definitely a parallel character, and a bit of foreshadowing. “There but for the grace of God, go I,” as a dear friend and reader once phrased it. Throughout the series, we see a number of characters deal with the same situation in surprisingly different ways; Zhu is someone whose strength lies in acceptance, in maintaining her dignity even while knowing she is probably doomed.

Phil: Let’s talk different cultures. Would you say that there is any significant difference between Philippine and American definitions of ‘strength’ or what a ‘strong’ woman should be like? Given that you drew heavily on your home culture for this series, how did those differences (if any) play into your writing?

Kay: There is, definitely. The Philippines, at its core, is a matriarchal society (although several hundreds of years of colonialism under two very patriarchal cultures did its part to muddy that). In our ancient past, women shamans were seen as some of the most respected members in society. Many of our ancestors would get tattoos to celebrate their accomplishments, but women automatically “earn” tattoos by virtue of being born. It doesn’t mean men don’t have power, either, but it’s a society with established roles for both genders and where women hold great influence.

There is a lot—arguably more—pressure put on daughters, especially eldest daughters, for instance. Not only are you expected to be able to compete academically and professionally, you’re also expected to be a “rock” for your family, to be the primary caregiver for your children, to take care of the household, and to keep the peace. You have on one hand this society with established gender roles, but is also comfortable balancing these roles with power.

There is a lot—arguably more—pressure put on daughters, especially eldest daughters, for instance. Not only are you expected to be able to compete academically and professionally, you’re also expected to be a “rock” for your family, to be the primary caregiver for your children, to take care of the household, and to keep the peace. You have on one hand this society with established gender roles, but is also comfortable balancing these roles with power.

So while in some cultures, a woman is often pressured to shed traditional gender roles in order to be seen as competent in a position of power, that is normally not the case in a society where grandma is easily the voice of authority in a family. The Philippines is a country that elected a “housewife” for a president some 30-odd years back, for example—a woman who used her femininity as the core of her campaign. A woman so respected that when she died, her son, who wasn’t running for president, somehow made it to the race…and won. In comparison, America has yet to elect a woman president. Being a woman, being a mother, being a wife, being a daughter… I’ve never gotten the impression that these things stand in the way of accomplishing my dreams. They can make them challenging, of course, especially with the way society is set up to make things harder for a woman, but Filipino culture in particular has taught us to take some hard punches. Being a woman is hard, our elders tell us, but you bear it. You bear it, and therein lies your power.

The theme of the series isn’t then about a woman trying to prove herself as good as a man. That’s already established—when you already hold that power, when you already know your strength, you don’t have to prove anything. Tali’s father never wished she was a son. But this opens up other challenges for her. Exploring strength in this case revolves around this resilience, in weathering the storm, in sacrifice, which are all lessons abound in Filipino culture both in men and women. But the challenges of womanhood are still there, which lends the different angle this series chooses to explore.

Phil: Do you think your readers picked up on this subtle but important change due to cultural context? Or have they rather ascribed any different expectations on the part of Tali’s society to her being an ‘exceptional’ character? In fact, what has reader response been to your protagonist? Has it surprised you, or proven to be what you’d hoped?

Kay: I feel like for the most part, this went by unnoticed, particularly since The Wolf of Oren-yaro involves Tali running around in a strange country with her authority diminished. I think this lack of cultural context also resulted in some people becoming frustrated with her attempt to hold her family together despite coming off as a relatively “bad ass” female character. Why did Tali keep quiet, instead of declaring war on her husband from the get-go? It’s because where Western ideals value the individual, Filipino ideals value family, blood, and togetherness. There is a term called amor propio, for instance, which translates to a sense of “self-worth” or “self-respect” or maybe even “pride”… and not only must you be watching this in yourself, it is required that you take care of another person’s. So Tali refusing to talk about certain issues, despite the power she holds, is her maintaining amor propio in her husband, her family, and her husband’s family. This doesn’t make her a “weaker” character—she is simply holding true to her cultural values. She’ll still bust your face open if you piss her off…

So for the most part, I’m pleased with the response, particularly because I am getting both sides—I am getting people who empathize with her and understand her challenges, and I see others who don’t, who write her off as irritating, even dumb, thinking that this depiction of a ‘queen’ is unrealistic (which it could be, depending on what other queen you’re comparing her to). It’s occasionally disheartening to see this lack of empathy with struggles that many women face in real life, every day.

Phil: Have you noticed a gendered character to these reactions? Do people who identify as female sympathize with Tali more than those who identify as male?

Kay: I think so. It’s always interesting to see the women chime in—the nuances in the conversations have been enlightening, particularly when people draw from their own experiences to fuel these discussions. For example, when the topic of Tali’s husband comes up, there are people who empathize deeply with him, and others who just want to kill him. I’ve had people tell me they feel her challenges strongly, that it mirrors theirs.

That’s not to say men haven’t sympathized with her at all—far from it. I don’t write “for” a certain gender of an audience, but of course the nature of the beast simply means that people who have gone through similar circumstances would see more, and understand more, than those who haven’t. I think I’m particularly pleased that there are others who do feel her situation, who go out of their way to experience and even enjoy the story of a character with circumstances vastly different from their own.

So the response generally has been amazing, and I’m hoping more people see there is a demand in the genre for stories like this: stories with real, breathing women as main characters, flaws and all.

K.S. Villoso grew up in the slums of Manila before moving to Canada in her teens. She now writes fantasy with themes shaped by her childhood–stories of struggle, hope, and resilience amidst grim and grit. Her debut, THE WOLF OF OREN-YARO, will be released by Orbit in early 2020. Click here to find out more.

Phil Tucker is a Brazilian/Brit that currently resides in Asheville, NC, where he resists the siren call of the forests and mountains to sit inside and hammer away at his laptop. He is the author of the epic fantasy series Chronicles of the Black Gate, as well as the Godsblood trilogy and the LitRPG series Euphoria Online. Click here to check out Phil’s books.

THE WOLF OF OREN-YARO is available in ebook format now, and will be released in paperback in February 2020.