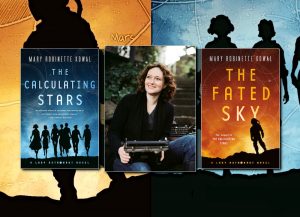

Interview with Mary Robinette Kowal (THE FATED SKY)

Joining us on the Hive today is Hugo Award-winning author Mary Robinette Kowal!

Joining us on the Hive today is Hugo Award-winning author Mary Robinette Kowal!

Mary Robinette Kowal was the 2008 recipient of the Campbell Award for Best New Writer and her short story “For Want of a Nail” won the 2011 Hugo. Her stories have appeared in Strange Horizons, Asimov’s, and several Year’s Best anthologies. She is the author of Shades of Milk and Honey and Glamour in Glass (Tor 2012).

Mary was kind enough to chat to The Fantasy Hive back in August about her Lady Astronaut series.

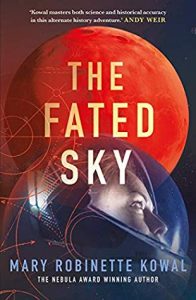

Welcome to the Hive, Mary. Your new novel The Fated Sky is out now with Solaris in the UK and Tor in the US. Would you be able to tell us a bit about it?

Certainly. It’s taking place in the early 1960s; in 1952 in this world a meteor slammed into the Earth, kicking off the space programme early and fast, so this is a mission to Mars, and it is staffed with men and women from all over the world.

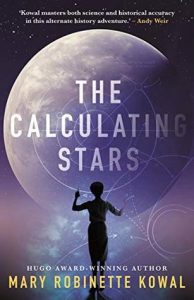

And it’s the follow-up to The Calculating Stars, which is up for a Hugo shortly at WorldCon [EDITOR’S NOTE: It won the Hugo!], so how are you feeling about that?

Yes. I’m feeling good. So it’s just won the Nebula and the Locus Awards, so the nice thing about that is that I’m not worried about am I going to win an award. It’s more that it feels very comfortable knowing that I’ve written something that people think is worthy of winning, even if it doesn’t actually take the trophy home. So mostly I look at the Hugos as a chance to buy a very pretty gown, which is the only thing that I can control, because the work is the work and at this point all of the voting has happened, so I’m in a Schrodinger’s world right now. I have both won and not won simultaneously.

Both novels feature your character Elma Yorke who first appeared in the short story The Lady Astronaut Of Mars. Where did this character come from originally, and when did you realise you didn’t just have a short story but a series of novels?

Both novels feature your character Elma Yorke who first appeared in the short story The Lady Astronaut Of Mars. Where did this character come from originally, and when did you realise you didn’t just have a short story but a series of novels?

The genesis of The Lady Astronaut Of Mars is that I was asked to write a story for an audio anthology called Rip Off. We were supposed to start with the first line of a famous story, and I chose The Wizard Of Oz. But I wanted to write a first person story and I wanted an older protagonist. So Elma in that story is based on my interactions with my grandmother. I wanted an older southern woman who was intelligent and in a committed loving relationship. Then from there when I went to do The Calculating Stars, which happens forty years before, I had to think about what she would look like younger, how she had become known as THE Lady Astronaut of Mars, since clearly there were other astronauts. And so exploring that was what led me to the younger Elma.

You’ve just had a third and fourth book in the series scheduled by Tor. When you started The Calculating Stars, did you realise quite how far it would go?

Oh no, The Calculating Stars was supposed to be a single book, actually. It was supposed to be a single standalone book, and I got about two thirds of the way into it, and my original plan had been that I was going to structure it as three connected novelettes, since the original had been a novelette. And I got through the first two and when I was working on the third, realized that decisions that were fine if it were a standalone novelette were totally unsatisfying as the last third of a novel, because I was having to skip big emotional beats and things like that. So I went to my editor and I was like, structurally I think this needs to be two books. And we talked it through, she agreed, so we split it into The Calculating Stars and The Fated Sky. The first novelette is part one of The Calculating Stars and it’s more or less the same, I was able to unpack some things. The second one is vastly unpacked, and then of course book three is its own thing. But even there I structured it as a duology, and I knew that there were things obviously that happened later because I have The Lady Astronaut Of Mars. So I know that there’s interstitial material. One of the things that I do when I write is that I will jot notes about potential stories in the same universe, but I did structure The Calculating Stars and The Fated Sky to be a duology, and book three, which I finished last week, is a parallel novel to books one and two. So you can read it by itself, or you can read it in conjunction with the other two. You can also read the other two and stop and never read any of the others. Although obviously I hope people will read all of them!

You started out with the character at the end of her life and move backwards. Is it fun to write towards a known endpoint?

It is. One of the things that having that as a guidepost does for me is that, I know that I’m writing to a hopeful future, because I’m writing towards a future in which Mars is settled by an international group. I’m writing towards a future where this couple are still in a committed loving relationship. And so that informs the decisions that I make, when often when you’re doing something like this you want to make things worse and worse and worse, I have to think carefully about the channels in which I make things worse.

One of the striking things about the novel is that both the historical detail and the science behind the early space travel is very thoroughly researched. Was this something you wanted to include when you were writing these stories?

Oh yes, mostly because I’m a giant geek. This was my opportunity to indulge all of my fascination with NASA, and space travel, and that was completely self-serving and the big challenge was not putting in everything that I learned. That was the hard part. I’m like, but wait, did you know… no one needs to know that. But it’s so cool!

Speaking of particularly unusual fields of knowledge, you recently posted a very interesting thread about how astronauts go to the toilet…

Yes, and that was actually only a portion of what I learned about peeing in space. The Fated Sky has an entire chapter that is nothing but a zero g toilet repair. And so I had to learn a ridiculous amount about how the toilets worked, and the other complications and fluid dynamics, and could not fit it all into the novel, so this was my opportunity to go, but look! One of the things that I regret that I learned after I wrote the book was that because of the disinfectant that they use on the ISS the pee is bright purple and acidic. And this happened, in real life, they had a toilet malfunction on the ISS, and there was a spinning globe of pee and it was bright purple, I’m just like, ah, such a good detail! I just have the spinning orb. If only I’d known it was purple!

The novels show both women and people of colour being involved in the space programme. Was it very important to have this as a balance to our view of the real world space programme and the people it excluded?

The novels show both women and people of colour being involved in the space programme. Was it very important to have this as a balance to our view of the real world space programme and the people it excluded?

Yes but more for me was that women and people of colour were involved in the space programme and they were written out of it, in the real world. So I wanted to make sure that they were represented, and that people were reminded that we have this picture of it being an all-white programme, and certainly it centred white men. But that they went to space with the aid of all of these other people. And I also wanted to really try to get that back in there. One of the things that I do when I write these days is that I assume that women and people of colour, disabled people, LGBTQ, that they were there and that they have been erased. So I always start my research process by going to look for them. And the other thing that I very much wanted was to just not ignore the realities of moving through the world like that, so it’s not so much that I feel I was writing about the civil rights movement, but I just wasn’t ignoring that it existed.

How much research goes into something like The Calculating Stars?

A lot! So, the way I worked, especially with this, the amount of science that I needed to thoroughly understand was greater than I had the time for. So what I do is I do broad stroke research to get kind of a general idea, and from that construct my synopsis. Then I begin to do tighter research based on the synopsis, like ok Elma is a mathematician so I need to understand orbital mechanics. I do not need to understand how rocket ships actually work, because she doesn’t fly one and she doesn’t build one. So there’s a limit to how much I need to know there. I don’t know what’s inside the thing. And then when I’m writing, I do what I call spot research, which is I hit a thing that I don’t know, and then I will look that up specifically. In practice the way that works is that I will often be writing and hit something and just leave a placeholder for myself to go look it up later. Like, the captain fiddled with the jargon, and said, “Jargon!” as he jargoned the jargon. And then I’ll go and look it up. Or in this case, I had astronauts and rocket scientists and flight surgeons, and I would send them the relevant section and say, will you play Madlibs? So technically sections of this are written by actual astronauts. So yeah that was very cool. All of the math, if there are actual numbers on the page it is correct and not my math.

These books are quite different from your previous series, the Glamourist Histories. How did you find the transition from Fantasy to Science Fiction?

The secret is that I don’t think that there’s a difference. There are many people who will be upset by this, but I think that Fantasy and Science Fiction are set dressings, that you’re still dealing with a story of ideas, and whether it is cloaked in lace, or in rocket suits, it’s an aesthetic. In The Calculating Stars, I am not good with math, so I basically treated math as a magic system. And in Shades Of Milk And Honey, the Glamourist Histories, I treated magic like science. In my head what’s happening in the Glamourist Histories, the way Glamour works is that they’re manipulating the electromagnetic spectrum, and they’re moving wave forms but not particles, so that’s why it creates an illusion but it doesn’t actually warm things. So I’d thought through all of the science of it. And The Calculating Stars I’m like, math is amazing! How is she doing that calculation? I have no idea, but she calculated something!

They do both have the historical elements to them. Is that something you’re particularly drawn to?

I am. In my short fiction I write all over the place. But in my novels, one of the things that I enjoy about using an historical frame is that it allows me to talk about contemporary issues in a way that is more accessible to readers. There are a lot of things that have not changed. I’m dealing with gender issues in the Regency, in the 1950s, I dealt with them in World War I with Ghost Talkers, these are things that don’t change, unfortunately. So that’s one reason. On a more practical reason, I wanted the people that were coming to the Glamourist Histories because they liked historical things to have an easy way to follow me as I transitioned into writing science fiction. And also rockets!

For the Glamourist Histories, you had a period dictionary for words that were period appropriate, which is one of the things that makes them read like a Regency novel…

Yes. So I made what I call my Jane Austen spell check dictionary, where I took the complete works of Jane Austen, used a concordance engine to turn them into a list of unique words, and used that really as my custom spell check dictionary. So it would underline any word that Jane Austen did not use, that then allowed me to go look it up. The OED, it’s a beautiful thing, the thesaurus has synonyms listed in order of when they came into the language. It’s really sexy. So I could look up words to see when they came into the language and if it shifted. It did not save me from words that she used but the meanings shifted, but it caught many things.

As well as writing books you are also a voice actor for audiobooks. Do you find this gives you a feeling for the sound of words read aloud that you take into your fiction?

Absolutely, that’s the reason that The Calculating Stars and The Fated Sky are written in first person. Because the genesis was an audiobook, and first person tends to work better on audio. What it specifically gives me is an understanding of punctuation. Writing developed to convey the spoken language, and punctuation is how we encode the natural pauses and rhythms of speech. So that plays in a great deal in the way I write everything. One of the other things I do as part of my writing process is that after I’ve written a thing I read the entire thing aloud before I narrate it.

On top of that you’re also a puppeteer. This is a day job that is also creative and involved in telling stories. Do you feel that it feeds back into the writing and vice versa?

The interesting thing is that character creation, all of that, world building, these translate directly into the way you approach writing. The problem is, that, because they translate so directly, when I am designing and building a show, my desire to write drops, because it uses the same part of the brain. When I’m writing, my desire to design and create new shows almost vanishes. However, performance is completely compatible because it does not use the same part of my brain. Performance is about audience connection and while that happens with the writing, it’s not triggering all the world building, character creation, problem solving things that writing does, and that design does.

And presumably that aspect of performance comes into reading audiobooks as well.

Yes. I like to joke that audiobooks are like puppetry without the pain. I’m allowed to sit in a comfortable chair, I do not have to lift anything over my head, I’m not in an awkward position. If I mess up, we just record it again. There’s no live audience, nothing is going to fall on me.

What’s next for Mary Robinette Kowal?

Well, having just finished book three, the next thing that I am writing is a standalone which is basically The Thin Man in space. It’s straight up science fiction, it’s a locked room murder mystery on an interplanetary cruise ship going from the moon to Mars, with a happily married couple and their little dog.

Thank you Mary Robinette Kowal for speaking with us!