In Medias Res and Then Some: Beginning THE LAST ROAD (Guest Post by K.V. Johansen)

“Begin at the beginning,” Holmes (or Lord Ickenham) might say, but storytellers from Homer on have been beginning in the middle of things. That’s often taken to mean starting in the middle of an incident close to the true beginning, and filling in a bit of backstory after to get you there.

The Last Road was a difficult book to do either with, because I could not find the beginning and wasn’t even sure about the middle. It was like a giant ball of yarn that a dog had been at — infinite knots and a bit grubby from too frequent chewing over. I knew quite a lot of what should happen, generally; I knew roughly where particular characters had to arrive in their lives to bring about the conclusion; I could not see where it began.

Groping after the start of the various threads, I wrote and discarded draft after draft of the first third or so of the book, going through phases where Holla-Sayan was spying in the west accompanied by a descendant of one of his brothers, or a girlfriend, or Mikki … I wrote versions where Yeh-Lin and/or Nikeh and/or someone who isn’t in the book any more was undercover in a cult that bore only the faintest resemblance to the form the All-Holy’s religion eventually took. I wrote an episode in which Ahjvar was sent by Ghu south over the sea to the Nalzawan Commonwealth and hung out briefly at a university there among the wizards and scholars and priests …

Nothing worked.

I wrote a hermit on a mountainside in a remote part of Pirakul and that was right, but it was not a beginning, except for the hermit.

I wrote a whole quarter of a book that turned out to be a different book in a different world and nothing really to do with this story at all.

I began to panic, because none of this was getting me anywhere. I tried writing outlines that went dead in my hands. I’m not good at outlines (though lately I’ve worked out a system that uses them as a way of thinking aloud at myself, and so long as I don’t have any commitment to trying to write that outline, it actually helps as a rough map.)

Meanwhile, though, all these chapters around the character of Sarzahn were taking shape in my mind, and pulling everything else into order. Problem was, that was the middle of the book, not the beginning.

Eventually, I gave up and wrote that middle section of the story. Worry about the beginning later, I decided. Once I’d written that ‘middle’, though, it felt right, as though that was where the book should begin. Everything that came before was leading up to that, and had too many scattered starting points in geography and in time for one alone to function as the way into everything else. Having recognized that, I was able to go back and write the stories that brought everyone to the point where the book begins now, with no doubt about what those stories should be.

I still assumed that having finally written both a middle and a beginning, I needed to rearrange them, put the earlier events at the beginning, the middle in the middle. This wasn’t a bit of flashback; it was a huge section of the book, after all. But the pacing felt all wrong when I experimented with that chronological approach.

I realize now that what I was subconsciously understanding was that those episodes earlier in time felt like separate stories. The pieces made a pattern once they were gathered together, but only in relation to what would follow them in time — they were the scattered foundation-stones that didn’t make a satisfying, three-dimensional shape on their own; they needed the context of the building they would support. To feel whole from the beginning, the story really did need to start at the point where the All-Holy was posing an immediate threat to Marakand. To leave the middle phase of the story as Part One, and the earlier events that led up to it as Part Two, worked. That way, the story began with characters in situations that had obvious connections with one another and with the larger crisis unfolding along the caravan road. It created drama and suspense. How did they get there? What had happened to cause this situation? Where did so-and-so come from and what was driving them to do the things they were doing? How were they going to survive long enough for the rest of the book to happen?

And why does Moth no longer have Lakkariss, the sword given her by the Old Great Gods and the only weapon capable of destroying a devil?

In The Last Road, for the significance of the smaller things to be felt, the consequences have to be known. It’s a kind of reverse foreshadowing. When you come to Part Two and see Ahjvar encountering Ailan in Star River Crossing, or Jolanan and Holla-Sayan sharing that first cup of tea in the dark night of a Reyka’s camp, or Moth stirring out of her long stillness in the icy north, you can anticipate what’s coming. There’s the satisfaction of watching these pieces fall into place, revealing the details and emotions of what was only hinted at in Part One — and you still don’t know how it’s all going to work out, but now you care, whereas I found when the multiple beginnings came piecemeal at the beginning, I spent more time, as a reader, wondering what the pattern was going to be, than enjoying it as unfolding story. It’s connections and interweaving that make Story, after all.

And it worked for Homer. You can’t get any more epic than that.

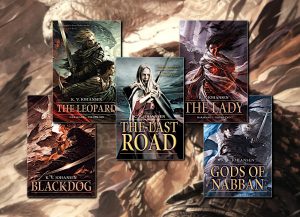

K.V. Johansen is the author of the GODS OF THE CARAVAN ROAD. The fifth and final book in the series, THE LAST ROAD, will be released on October 22nd 2019.

[…] in a wonderfully KV Johansen way – never one to take the direct route, as described in a guest blog on this site. First we see the height of the wave, the panic and flight and steely determination in the face of […]