THE GIRL AND THE STARS by Mark Lawrence (Book Review)

And so I finish 2019 as I started it: with a review of a Mark Lawrence ARC, my fifth of the year and my 50th book overall, so a suitable point at which to take a seasonal break.

The Girl and the Stars is Mark’s thirteenth traditionally published novel and the second time he has returned to a world built and explored in a previous complete trilogy. Six years ago Prince Jalen Kendeth first walked the same broken earth that Jorg Ancrath had bestrode (bestrodden?) with such brooding magnificence. We followed both these male protagonists through the intimacy of a first-person point of view and found neither of them to be the archetypal hero; one drawing inspiration from the sociopath Alex in A Clockwork Orange, the other a womanising fantasy Flashman.

The Girl and the Stars is Mark’s thirteenth traditionally published novel and the second time he has returned to a world built and explored in a previous complete trilogy. Six years ago Prince Jalen Kendeth first walked the same broken earth that Jorg Ancrath had bestrode (bestrodden?) with such brooding magnificence. We followed both these male protagonists through the intimacy of a first-person point of view and found neither of them to be the archetypal hero; one drawing inspiration from the sociopath Alex in A Clockwork Orange, the other a womanising fantasy Flashman.

In The Girl and the Stars, Lawrence gives us another tale set on the ice-bound world of Abeth, a planet barely warmed by a dying star in the endgame of the universe’s inevitable submission to the rise of entropy. Like Nona before her, Yaz is an adolescent under duress, tested almost to destruction by a harsh environment and harsher company. Nona lived in the thin habitable greenbelt around Abeth’s equator – or rather, Nona will live there, for Yaz’s tale predates hers, and by such a margin they are unlikely to have that path-crossing moment we saw in The Wheel of Osheim, where Jorg and Jal compared scars and swapped advice.

Yaz is of the Ictha tribe, the most northern of the ice tribes, in a region so cold that not just water but carbon dioxide mists on the breath. (That means -40 degrees by the way, and no need to convert the units for American readers; -40 is the same in Fahrenheit and Celsius. In short, it’s bloody cold.)

Each of us sees a book through the lens of our own past, and so each reader-author pairing fashions its own unique experience, with different emphases placed on different elements. It’s like the height of 1980s hi-fidelity – the graphic equaliser where each of ten frequency ranges had an adjustable volume setting to tune the listening experience to your own ear. For me, as you may have guessed, science is one frequency that my reading ear responds to, and Lawrence, with his own background in research science, seasons his story with moments of scientific magic – not least when Yaz encounters a mysterious elder perched by a pool of water supercooled to a temperature well below that where ice should have formed. The elder anthropomorphises the phenomenon: “It wants to change but every change must start somewhere and in this pool the change has nowhere to start.” But then when Yaz drops a tiny piece of grit in the pool, crystals of ice at last have a purchase on which to form and the whole pool is instantly tipped from one (liquid) state to another (solid) state. That breath of physics had me murmur a silent yee-hah at seeing a representation of my favourite subject in fiction, but Lawrence also makes it the allegory for his entire story. Yaz is the grit dropped – literally – into a system pregnant with the potential for change, for transformation.

(Here’s an example of supercooled liquid crystallising)

But I race ahead of myself. We meet Yaz and her tribe heading to a ceremony at the Black Rock in which the children are to be tested in a brutal rite that makes the Spartans’ abandoning of babies on the hillside seem positively civilised. It is not too much of a spoiler to say that Yaz ends up in a maze of tunnels and caverns beneath the glaciers on a quest to save her brother Zeen in that liminal space where the ice grinds over the bedrock. This is the central plot strand upon which all that follows is hung. However, Yaz’s arrival in this subglacial world of grinding ice and fractured communities is the catalyst, the piece of grit in the supercooled pool, that precipitates a whole world of change.

I suppose this could have been Zole’s story, the enigmatic and laconic Ictha – the chosen one – from the Book of the Ancestor whose quest carried her on a parallel course with Nona’s. Save that that quest was over, so maybe Zole was merely the inspiration that had Lawrence wanting to tell the tale of a hardy and determined young woman of and in the ice. To explore the backstory of the people who made Zole.

The glaciers of Antarctica are several kilometres thick, a hulking hide of ice pressing a whole continent deep into the earth’s mantle, so much so that the lowest land on earth is not the Dead Sea but in fact the bottom of an ice-filled crevasse three and a half kilometres below sea level – as reported here. This is the kind of world Yaz finds herself in, lit by its own stars – tiny fragments of broken magic from the lost civilisation of “The Missing,” swept up within the ice by the remorseless grind of the glaciers as they scoured the great lost cities from existence. Yaz has an affinity for those stars, an ability to draw on their magic, which makes her different and valuable to the subglacial communities.

And there are communities down there. The broken, those cruelly discarded by the priests of the ice, tested and found filled with some imperfection that will make them a burden on their kith and kin. Better to cast them away beneath the ice. This is another of those themes that resonate as the Yaz’s story unfolds, the hierarchy of value that society places on human lives, the assumption that there is some threshold beneath which a human might be discarded. Lawrence’s first trilogy plays with the word both in setting Jorg’s story in The Broken Empire, and in the dedication at the front of Prince of Thorns.

There are also the tainted, caught and infested by demons, black shadows from within the ice that slip beneath the skin to possess the body and torment the soul. I find it curious to contrast Lawrence’s conception of demons with Peter Newman’s. In The Red Queen’s War, Lawrence had Jal and Snorri infected by demons, and another subcutaneous sliver of demonic essence rode inside Nona for a fair portion of the Book of the Ancestor. Newman’s demons are – in both The Vagrant and The Deathless trilogies – more bizarre external constructions, strange corporeal creations of mis-formed or appropriated flesh that defy biology and yet ultimately attract a kind of pity. I find it curious how each writer’s demonic DNA emerges in slightly different forms in different trilogies.

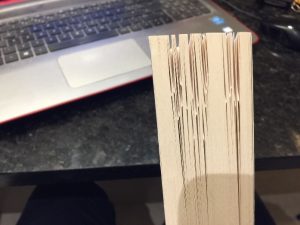

There is, as ever with Lawrence’s writing, a multitude of lines at which to smile and catch a breath. The downside of a hard copy is that I can’t make notes and bookmarks as easily as I would on a kindle. I am forced into the ultimate vandalism of dog-eared pages and pencil marks:

You can see here how often I had to stop and bookmark by hand. The blocks of unmarked pages are not a matter of any drop in quality so much as a reader’s restricted opportunities. It’s hard to scribble pencil annotations when you are reading in the small hours of the morning by the light of a phone filtered through a duvet cover as you try not to disturb the sleeping partner beside you who has to get up for her 8.00 am shift.

But here are just a few of the lines – among so many – illustrating either the economical elegance of Lawrence’s prose or the icicle sharpness of his insight:

The star’s stark illumination, slanting upwards, threw his face into a confusion of shadow and light.

We are the victims of our first friendships. They are the foundations of us. Each anchors us to our past.

Your life will run that much smoother if there are no untruths between your heart and your head.

(He is) the sort who would rather break something and own the pieces than see another hold it whole.

They tasted better cooked but her stomach was too hungry to care about her mouth’s opinions.

The new star burned a deep crimson … and filled the chamber with bloody light, making red and dripping spears of the icicles about him.

Normally only the warriors were allowed swords and spears but normal had made itself scarce of late.

In keeping with the pantser or gardener style of writing that Lawrence espouses, the plot is an organic one. Yaz follows the twisting turns of Lawrence’s quicksilver imagination, a writer who surprises himself as much as the reader with what happens between the top and the bottom of any given page. There is at times an echo of Alice in Wonderland, for Yaz has more than one fall that is deeper by far than any rabbit hole, and – like Alice – finds strange surreal places at the end of them.

The Missing – people gone from the face of the planet long before the Ancestors arrived in four ark ships to colonise Abeth – haunt Yaz’s story. The Broken subsist by raiding the ice-warped ruins of one of the Missing’s cities in search of precious iron, but the Missing themselves are a mystery. Like the aliens in the sci-fi classic “The Forbidden Planet,” they have vanished without trace as the cataclysmic consequence of some search for perfection, leaving behind a veritable Marie Celeste of abandoned technology and creeping malevolence.

Lately I seem to find myself thinking quite a bit about the different representations of cities in speculative fiction. With The Girl and the Stars, Lawrence creates a new entry in that catalogue with an almost sentient city, not quite as mobile as the Mortal Engines of Philip Reeve’s imagination, but just as dangerous to those that cross its path.

As ever, Lawrence plows a furrow between science fiction and fantasy, abiding by Arthur C. Clarke’s third law: that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Or as one of Lawrence’s characters puts it:

There is no such thing as magic. If a thing is part of the world, part of how it works, then it’s real and obeys laws just like gravity and electricity do.

Lawrence’s worldbuilding also shines in the portrayal of the hardy Ictha – the tribe that in time will spawn the formidable Zole. The harshness of their lives and the stoicism of their culture is summed up in the saying, “These things too the wind shall take.”

The Girl and the Stars drops the reader into a fresh new adventure full of all the poetic brilliance of Lawrencian prose. It’s the first in a brand-new trilogy, The Book of the Ice, and will be published on April 30th 2020.

What kind of person dog ears their books, intentionally??