THE WORD FOR WORLD IS FOREST by Ursula K. Le Guin (Book Review)

This is the latest “SF Masterwork” that I picked off a Waterstones shelf as part of my occasional self-education in the classis of speculative fiction. The advantage of the Masterworks is you get a little bit of an insight into the context of the original novella (a 1973 Hugo Award winner) through the introduction by Ken Macleod in addition to the Author’s introduction for a 1976 reprint.

This is the latest “SF Masterwork” that I picked off a Waterstones shelf as part of my occasional self-education in the classis of speculative fiction. The advantage of the Masterworks is you get a little bit of an insight into the context of the original novella (a 1973 Hugo Award winner) through the introduction by Ken Macleod in addition to the Author’s introduction for a 1976 reprint.

Le Guin wrote this short 128 page story in the late 1960s. No book is born in a vacuum entirely free of context and Le Guin freely admits “I succumbed, in part, to the lure of the pulpit.” At that time the USA was at war in Vietnam and a technologically advanced mighty military machine was being battled to a standstill by a ferocious but inadequately armed force defending their homeland. However, there are parallels and resonances to this book that extend both forwards and backwards from the time in which it was written. Like Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale,” Le Guin’s “The Word for World is Forest” has a message for the 21st Century as worldwide it seems politicians are determined to “Make Dystopia Real At last.”

Le Guin’s sets the plight of colony 41 or New Tahiti several centuries in the future when a spacefaring Earth based human society has met up with other cousin human civilisations. These races share a common genetic heritage and yet are far more diverse than the different ethnicities of Earth.

The heavily forested New Tahiti is a resource of valuable lumber for the now barren concrete wastelands of Earth. The colony has been in operation for four years and there is a plot hole in the economics of lugging lumber across a distance and delay of 27 light years, but – as MacLeod, points out – it is one to forgive as you descend into the depths of an intriguing tale.

New Tahiti is not uninhabited, its natives called it Athshe and they are the people of Athsheans. We must be grateful for Le Guin’s first editor who ensured she dropped the original title of Little Green Men, which would have done a disservice to the poetry of the story. However, the Athsheans are certainly diminutive – about a metre in height – and green-skinned – putting me in mind of a kind of furry Yoda. However, despite this significant difference in physiognomy they are as fundamentally human as the rest of the diverse races that make up Le Guin’s interplanetary colonising co-operative.

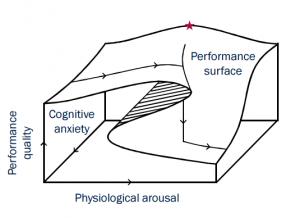

Their humanity is not so clear to many of the military force escorting and supporting the logging and colonising operatio – in particular the story’s antagonist, Captain Davidson, who dismisses natives as ‘creechies,’ to be exploited, tamed, raped and murdered as the mood takes him for in his eyes they are subhuman. The inherent pacifism of the natives’ culture, the gentle subtlety of the matriarchial structure, the diffuse spread of their forest village communities, brings about a submission to enslavement which simply reaffirms Davidson’s views. However, like every catastrophe curve, there is a point at which submission abruptly flips to rebellion, when flight – in body or mind – turns to fight.

The catalyst is a male Athshean called Selver who has been working with a human scientist Raj Lyubov. Lyubov’s job within the colony is a liaison with indigenous peoples, and from Selver he has learned much of the Athsean language and culture. However, an act of cruelty on Davidson’s part tips Selver into open rebellion not just in defiance of the human colonists but of his own people’s entire pacifist history and culture.

Le Guin may have been thinking of the deforestation in Vietnam and the dehumanisation of the enemy to justify attacks aimed at extermination. Certainly, the weapons of fire and destruction that Davidson rains down from hoppers that sound a lot like choppers, resemble the air-born gunships dispensing destruction and agent orange in equal measure.

However, the ill-managed deforestation that turns one of New Tahiti’s islands into an inadvertent desert reminded me of the dangerous deforestation of the Amazon. The casual disregard for the delicate balance of root systems needed to bind the soil and prevent wind erosion, the brutality towards indigenous people defending their home and habitat, the irreversible loss of species diversity, they all sound horribly relevant today.

However, the ill-managed deforestation that turns one of New Tahiti’s islands into an inadvertent desert reminded me of the dangerous deforestation of the Amazon. The casual disregard for the delicate balance of root systems needed to bind the soil and prevent wind erosion, the brutality towards indigenous people defending their home and habitat, the irreversible loss of species diversity, they all sound horribly relevant today.

There is another parallel too – with tales I read in “Bury my Heart at Wounded Knee,” Dee Brown’s history of the conquest of the American west told from the Native American perspective. A viewpoint I also saw depicted in “Soldier Blue” with its haunting theme song by Buffy Saint-Marie. McGregor is as evil a creature as any of those leaders of massacres at Bear River and Sandy Creek – such as Colonel Chivington, who said, “Damn any man who sympathizes with Indians! … I have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God’s heaven to kill Indians. … Kill and scalp all, big and little; nits make lice.”

When Colonel Dhong argues with a scientist against the fact that the Athsheans are as human as him, descended from the same Hainish stock, he dismisses it with a disrespect for science that would warm the prejudices of any modern-day creationist, anti-vaxxer, climate-change denier or flat earther.

“That is a scientific theory, I am aware-“

“Colonel, it is the historic fact.”

“I am not forced to accept it as fact,” the old Colonel said, getting hot, “And I don’t like opinions stuffed into my own mouth. The fact is these creechies are a metre tall, they’re covered with green for, they don’t sleep and they’re not human beings in my frame of reference.”

A cry of “my ignorant prejudice is of equal (or greater) value with your evidenced science” is one that we see too often these days. It is not just in social media but now the mainstream media bend over backwards in search for balance, oblivious to the fact that they do so on the edge of a precipice between right and wrong.

There is also of course, the element of slavery, a theme that has haunted all of human history up to the present day. For the Athsheans, whose passivity is interpreted by the colonists as effectively volunteering, there are pens to hold a workforce that the vastly outnumbered colony builders need. This fearsome human tendency to dehumanise its fellows in order to justify their mistreatment is a failing of morality that can never be called out enough. As I read this week of a prime minister insisting that “EU citizens have too long treated this country like their own” I am dismayed – though not surprised – that yet again a human leader should seek to define and weaponise the “otherness” of a target group of scapegoats, all for his own advantage.

So let Ursula le Guin have her moment in the pulpit, and let others in speculative fiction join her there, for there is little in our imagined futures that – for better or worse – is not an extrapolation from our human pasts.

So let Ursula le Guin have her moment in the pulpit, and let others in speculative fiction join her there, for there is little in our imagined futures that – for better or worse – is not an extrapolation from our human pasts.

Politicking aside, The Word for World is Forest is a decent story, well told with some inventive worldbuilding. I was struck by the centrality of dreams to the world of the Athsheans. Athshean men experience waking dreams that give them insights into the solutions to their problems. They flit between dream-time and world-time and the women act on the information revealed in dreams. Lybov describes the Athshean dream state as “a condition which related to Terran dreaming-sleep as the Parthenon to a mud hut; The same thing basically, but with the addition of complexity, quality and control.”

The prose is fluid and economical, a potentially epic tale delivered in just eight short chapters shared between three points of view. “Rain pouring down onto ploughed dirt, churning it to mud, thinning the mud to a red broth that ran down the rocks into the rain-beaten sea.”

The Athsheans are different yet easy to empathise with in their curious idioms of speech and culture, such as when Selver is roused from a long sleep. “Help me get up, Greda. I have eels for bones…”

One poignant aspect arises when Selver is acclaimed by his people as a god, which in the Athshean way is more a matter of semantics than deification. Just as Forest is the word for world, god is the word for translator, a bringer of new words. Selver has brought the meaning of death and destruction into the lexicon of Athshean understanding. “Selver, the translator, frail, disfigured, holding all their destinies in his empty hands.”

I had not realised until I came to look this up on Goodreads, that this standalone book is Hainish cycle #5, that is it draws on an interstellar network of peoples and planets that Le Guin had already devised. That may explain some of the Wildcard effects I felt, fully realised people making a guest or cameo appearance. Certainly, having that readymade universe enabled Le Guin to focus on the story and its very sharp points. The Word for World is Forest is an entertaining and thought-provoking story that has not outgrown its relevance because, sadly, humanity hasn’t outgrown its prejudices, only found new ways to enact them.