OF CATS AND ELFINS by Sylvia Townsend Warner (BOOK REVIEW)

“What is the prevailing mood of these stories we call folk stories? Is it heated and sentimental like the undoubted products of the human imagination – or is it cool and dispassionate – what you like to call objective – and catlike? What are the qualities these stories praise – whenever they unbend sufficiently to praise anything – chivalry and daring, or sensibility and reserve?”

“What is the prevailing mood of these stories we call folk stories? Is it heated and sentimental like the undoubted products of the human imagination – or is it cool and dispassionate – what you like to call objective – and catlike? What are the qualities these stories praise – whenever they unbend sufficiently to praise anything – chivalry and daring, or sensibility and reserve?”

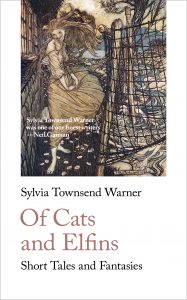

Following on from their welcome reissue of Sylvia Townsend Warner’s The Kingdoms of Elfin (1977), Handheld Press have released Of Cats and Elfins, a short story collection that collects the remainder of Warner’s short fantasy fiction in one attractive package. The collection contains the four remaining Elfin stories not collected in The Kingdoms of Elfin (1976-84), her essay on the nature of fairies (1927), Warner’s take on Metamorphosis with ‘Stay, Corydon, Thou Swain’ (1932), and the entire contents of The Cat’s Cradle Book (1940), a collection of fables that mother cats tell to their kittens. Together, the stories offer a welcome return to the fantastic side of Warner’s imagination for new readers captivated by The Kingdoms of Elfin and hoping for more material, as well as illustrating that rather than just bracketing her career as a writer, there was a subtle strain of fantasy running throughout Warner’s life as an artist.

The collection opens with Warner’s essay ‘The Kingdom of Elfin’, which shows her depth and appreciation of the folklore that informs her Elfin stories. The four extra Elfin stories are all worth reading, and for anyone who loved The Kingdoms of Elfin it is a pleasure to find these extra stories waiting for you after you’ve finished the book. Although most of the stronger stories are included in the original collection, ‘Narrative of Events Preceding the Death of Queen Ermine’, ‘Queen Mousie’ and ‘An Improbable Story’ all contain enough of Warner’s mordant wit and the glacial cruel beauty of fairyland to make them worth visiting. ‘The Duke of Orkney’s Leonardo’ is a more substantial piece, a story of an ill-fated child’s gruesome transformation, with undercurrents of queerness and sly undermining of gender norms. It could sit happily with the best stories in The Kingdoms of Elfin, and makes the collection worth the asking price alone.

‘Stay, Corydon, Thou Swain’ is distinct from Warner’s fairy stories in style and content, but retains Warner’s gorgeous language, her appreciation for mythology and her stark cruelty to her characters. Following the level-headed Mr Mulready as he is swept out of his humdrum life and into peril and mystery against his better judgement by a nymph, it has echoes of Greek mythology and the sexual undertones of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, but transfigured to Somerset of Warner’s time. For Warner, the mythic and all it stands for hide in plain sight in the everyday, just waiting for foolhardy mortals to unearth them.

‘Stay, Corydon, Thou Swain’ is distinct from Warner’s fairy stories in style and content, but retains Warner’s gorgeous language, her appreciation for mythology and her stark cruelty to her characters. Following the level-headed Mr Mulready as he is swept out of his humdrum life and into peril and mystery against his better judgement by a nymph, it has echoes of Greek mythology and the sexual undertones of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, but transfigured to Somerset of Warner’s time. For Warner, the mythic and all it stands for hide in plain sight in the everyday, just waiting for foolhardy mortals to unearth them.

The bulk of the collection is given over to The Cat’s Cradle Book. Warner, like most right-thinking people, loved cats and she and her partner Valentine Ackland looked after many. The Cat’s Cradle Book brilliantly captures the character and sensibility of cats. Much like Warner’s fairies, they are sleek, beautiful, charming yet capricious, and self-reliant; existing parallel but aside to mere human concerns. Warner brilliantly draws the line between the stark coolness of folktales and the attitude of cats by attributing her folktale-inflected stories to cats, reminding us that theearlier versions of fairy tales and legends are from an older time in human history, and are much concerned with darkness and death. Many of the Cat’s Cradle stories feature cats and humanity’s relationship with them, sometimes affectionate, sometimes antagonistic, sometimes as a chaotic trickster figure. Frequently the stories take an outside view of humanity, from the point of view of animals or other aspects of nature. And frequently nature comes out on top. ‘Odin’s Ravens’ retells the morbid Chid Ballad ‘Twa Corbies’, with the ravens feasting on the metaphorical corpse of the old gods as much as the man fought over by two lovers. ‘Virtue and the Tiger’ asks what possible use human values could be to animals, whilst ‘Apollo and the Mice’ sees the sun god taking the side of mice in their conflict with a farmer. Like the Elfin tales, they are delightfully subversive. ‘Bluebeard’s Daughter’ is a sequel to the grisly tale of Bluebeard, with his offspring able to learn the lessons neither of her parents were able to.

As with all Handheld Press books, Of Cats and Elfins is a masterclass in presentation. The book has a glorious cover, with a complementary Arthur Rackham fairy painting to complement the one on The Kingdoms of Elfin, and likewise has a useful introduction by Greer Gilman and extensive footnotes.