Writing Codices and Lore in Media

Writing on codices and lore in media, how that lore affects our consumption of said media, and effectively producing that lore.

To begin…

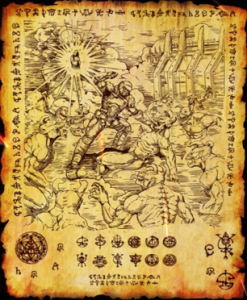

Doom: a 90s first-person shooter about blowing up, chainsawing, microwaving, gibbing and otherwise killing demons in any and every way possible. At first glance, the 2016 reboot/sequel is the same thing – a glorious romp through Mars and hell with updated graphics, blood-pumping intensity and plenty of homage to the original. If you really enjoyed the game, as I and many others did, it actually has a lot more under the surface that serves to enhance every rip and every tear you perform in the game.

I’m going to be talking a lot about Lore, how it changes the way we consume different forms of media, how it can enhance and sometimes detract from what we enjoy, and quite a bit about the actual writing behind a ‘Codex’ or lore book.

So, why Doom? It’s a good example because I know the lore well, and I had two entirely distinct experiences on two separate play-throughs. The first, completely blind, and the second with all the knowledge I could possibly find on the Doom Slayer and his antics; from Reddit theories, to the codex itself and from the three previous games that tie into all of that lore. The Slayer is a character that is portrayed entirely wordlessly, and all from the first-person perspective, leaving only his hands to do the talking, but boy do they talk. To the way he shoves away a monitor spouting useless exposition, to how he destroys the speaker telling him that ‘everything was for the betterment of humanity’, ironically over a human corpse.

As a player, you think: ‘Cool, the Slayer embodies the mindset of the player. I don’t want the exposition and talking, I just want to play the game, it’s quite self-aware!’ and yes, that is somewhat part of it. However, the Slayer’s actions are mediated by aeons of bubbling rage all explored through a deep and rich history of the ‘Doom universe’. Knowing that the slayer has been the bane of hell for untold eternities, that he is literally the only thing hell fears, that a seraphim granted him immortality, swiftness and strength, and the ’wretch’ of hell forged his armour in the hellfire forges, is not only insanely cool – but strictly enhances the feeling of the gameplay. Now it’s not only a cool FPS with some great homages to the past, but one of, if not the greatest power fantasy afforded by a video game. It turns it from a fast and mechanically sound FPS to hell’s slasher horror game where you play as the villain. The fear in the eyes of Imps and Mancubuses as you rip and tear through the hordes of the wicked changes from a cool little touch, to a main proponent of the gameplay – again in service of empowering the player.

As a player, you think: ‘Cool, the Slayer embodies the mindset of the player. I don’t want the exposition and talking, I just want to play the game, it’s quite self-aware!’ and yes, that is somewhat part of it. However, the Slayer’s actions are mediated by aeons of bubbling rage all explored through a deep and rich history of the ‘Doom universe’. Knowing that the slayer has been the bane of hell for untold eternities, that he is literally the only thing hell fears, that a seraphim granted him immortality, swiftness and strength, and the ’wretch’ of hell forged his armour in the hellfire forges, is not only insanely cool – but strictly enhances the feeling of the gameplay. Now it’s not only a cool FPS with some great homages to the past, but one of, if not the greatest power fantasy afforded by a video game. It turns it from a fast and mechanically sound FPS to hell’s slasher horror game where you play as the villain. The fear in the eyes of Imps and Mancubuses as you rip and tear through the hordes of the wicked changes from a cool little touch, to a main proponent of the gameplay – again in service of empowering the player.

Doom’s lore is excellently entwined with the gameplay, and enhances every crevice of the game – but one of the reasons it is so excellent is also because it is unnecessary. Just by playing the game, and ignoring every codex and piece of lore outside of the little that is in the main narrative, you will have fun. The media stands on its own two legs without any of the extra context or cool backstories – and if none of the lore existed it would still be worthy of all the same praise it already received – because that is what lore should be. Icing on the cake.

With great backstory, comes great complexity…

If lore is intrinsic to the enjoyment of a piece of media, then for some people – especially those wanting to jump into a franchise already way into its life cycle – that lore can be rather intimidating. Warhammer 40k is a great example of this. I used to play a lot of the tabletop game, and was very much into the Dawn of War and Space Marine games too, and as much as I did enjoy them I never really got that much into the lore. I know what I need to know of the basics and that’s about it. For playing the tabletop, knowing little to nothing of the lore isn’t too much of a problem, the game itself is fun without knowing why the big blue marines are shooting the weird green Boyz. On the surface Warhammer lore isn’t too hard to understand either, it’s grimdark, everything sucks, everyone is evil in some way or another.

The deeper lore, the interesting tidbits, alliances and wars that all take place in the universe are actually rather intimidating if you gain an interesting in the 40k universe. Before you even begin looking into stories that take place in the universe you must understand the Adeptus Astartes, Mechanicus, the warp, the Emperor, and oh dear there are already words I don’t understand. This isn’t an inherent critique of Warhammer, or of having deep and complex lore, rather this is just one way that lore can deter someone before they have even made their way to the narrative. You cannot pick up a Warhammer novel without having some knowledge of the lore surrounding it, as a lot of the stories require an understanding of how the factions function and engage with one another.

The deeper lore, the interesting tidbits, alliances and wars that all take place in the universe are actually rather intimidating if you gain an interesting in the 40k universe. Before you even begin looking into stories that take place in the universe you must understand the Adeptus Astartes, Mechanicus, the warp, the Emperor, and oh dear there are already words I don’t understand. This isn’t an inherent critique of Warhammer, or of having deep and complex lore, rather this is just one way that lore can deter someone before they have even made their way to the narrative. You cannot pick up a Warhammer novel without having some knowledge of the lore surrounding it, as a lot of the stories require an understanding of how the factions function and engage with one another.

True Neutral…

Halo and Star Wars are two examples of the above not applying. The lore surrounding them, in my opinion, does not greatly affect the viewing experience of the films and the engagement of the games – and I believe this is mostly due to how far removed the lore is from the present timeline of the story at hand. This does not mean that the lore from either is boring or uninteresting, quite the opposite – I am a fan of both – but knowing of the precursors in Halo or of the first Sith in Star Wars does not in any significant way affect the narratives. This leaves lore as an ‘extra’, information that fills out the rest of a world that one is excited to know everything they can about. One does not have to know about the extra information in order to gain everything out of those experiences – because the lore is built as exactly that – more canon information without intruding into the present narrative.

There are a few exceptions within those two franchises of course – knowing how the spartan IIs came to be, the fall of reach, and ‘Operation Torpedo’ add to the depressive war story of Halo Reach but or the most part knowing about Halo’s pre-history is unnecessary. The same goes for knowing about Kit Fisto’s operations in the clone wars, and Plo Koon’s upmost respect for his clones. They may add to the emotion of seeing them die onscreen, but their part is so small that the added emotion is quickly wiped away by what is at the forefront of the narrative.

All of this makes Lore as an idea so much more fascinating to write. When writing a codex for a game, or extra stories on the side for franchises like Star Wars, you are engaging with an entirely different audience as when you are writing for an original idea. This audience is vastly hungrier for details about the world, as much as they are an interesting story set within it. It is like official fanfiction – where every new power and cool new thing added are more morsels to taste before the next big canon meal. So, then it becomes a balance of story vs detail. Do I want to spend two chapters talking about the intricacies of Mjolnir Mk V armour, or do I need to move on with my actual plot? The same rules for writing apply – you don’t want to bore your reader with walls of description – but you also want to give the people who came here for that information what they want. With this in mind, many books that add to the lore of these franchises are always in a fabulous balancing act of ‘Franchise information’ vs ‘New story’.

I wrote a piece recently called ‘The Badland’. It is an original story with no bearing on any existing media – but it is heavily inspired by a polish artist called Zdzislaw Beksinski. I bring this up because, upon completion, I found the piece read far more closely to a codex scripture you would find in a video game than a piece that stands on its own. The front story is poor the character more of an excuse to move the reader through the world than an agent herself – and yet I found it fascinating and immensely fun to write. When a piece of writing is tucked away in a menu, found only by those willing and wanting to know more about the world they’re playing through, I believe adherences to certain writing rules float away – not that they aren’t important, but somewhat forgiven if they are broken. I know that on its own this piece of writing is relatively poor and could be heavily critiqued, but under the guise of a codex entry, a description of the world the player is journeying their way through, I believe it is elevated beyond the sum of its parts. It is this context that can completely change one’s perception of a story. To come back to Doom as an example, ‘The Slayer’s Testament’ on its own isn’t too well written of a story. It has too much mystery and vague language that would lose the reader – if the reader did not gain the context s/he needed from actually playing as the character so vaguely referred to in the testament.

What to do with all these codices?

So, what about writing from lore? The best example of this would be any Lovecraftian story. The Cthulhu mythos has bred stories of all kinds that have an inherent link. Lovecraft’s ideas of madness, the unknown and unknowable cosmic horror is so open and so vast that any addition to it could feasibly exist within the same world. ‘An Inhabitant of Carcosa’ by Ambrose Bierce is a wonderfully Lovecraftian piece of worldbuilding and horror that, if the author’s name were changed, would be indistinguishable from the world Lovecraft had already set in place. Why couldn’t they’re be a hell, led by the yellow king whose name must not be spoken of and – oh dear. I’ve already gone deeper into the lore myself, because The King in Yellow, and the ideas about Carcosa were not created by one author, but several over many decades. Ambrose Bierce first named Carcosa, and later went on to elaborate on the King in Yellow. Hastur was then built upon by Robert W. Chambers in multiple short stories. Lovecraft himself mentioned Hastur (The King in Yellow, same entity) after he read Bierce’s work and referenced him in ‘The Whisper in the Darkness’.

Hastur is a character that no one person has created. It is an entity that has been elusively present for decades of horror writing – which only adds to the authenticity of the mythos itself. Lovecraftian stories built nowadays are all connected by this collaboration between authors, a mythos that is attached to and built on by author after author with ideas about what these entities are and how these creatures are manifested and what they can do to us – puny, tiny, insignificant humans.

Hastur is a character that no one person has created. It is an entity that has been elusively present for decades of horror writing – which only adds to the authenticity of the mythos itself. Lovecraftian stories built nowadays are all connected by this collaboration between authors, a mythos that is attached to and built on by author after author with ideas about what these entities are and how these creatures are manifested and what they can do to us – puny, tiny, insignificant humans.

As such, before the first word has been written on a page, these stories are elevated by the context they are placed in. Writing a story with Lovecraftian elements and no references at all to the Cthulhu mythos is still connected to those stories through feeling and the years upon years of worldbuilding done to them. These eldritch gods exist in the background of the most minor Lovecraftian stories that affect only one person or a small town, even when the creature focused upon in the story is not too scary or isn’t that interesting, the story itself is lifted up by the works of previous authors hanging over the world’s head. A weird item making people go insane and crazy in a village – vs an item in a village making people go crazy whilst Hastur, the king in yellow, torturer of man and unfeeling cosmic entity is watching over is far more terrifying – all without typing a word about him/it/indescribable/₼₻₽₸₵₹.

To conclude…

Mass Effect, Alien (by Ridley Scott), Assassin’s creed and the Witcher all have this type of connected Lore too, though to a far lesser extent. They have connected worlds that practically breed stories out of the lore itself. Any historical story could have an Assassin insert – adding it to the lore of the world with little effort. There are an infinite number of Assassins, times and places you could set an Assassin’s Creed story. Mass Effect has an entire galaxy full of different aliens with histories and futures all of their own, in addition to the galactic community ran by the citadel, and the outer rim ran by pirates, outlaws and mercenaries. Alien’s history is currently being played with by big-screen movies, but a lot of its lore mixes with James Cameron’s predator, creating a whole Aliens vs Predator world to play with. The Witcher books are all short stories themselves, that focus as much on world building as they do character and narrative progression. All of these examples show how codex writing can be implemented into building whole new stories – or using worldbuilding as your story in the case of The Witcher and some of Mass effect, by utilising small but interesting short stories that feed tidbits of information to your audience.

So, if you started this article with just a minor interest in Lore of your favourite franchise, go dive in. I promise, when you come back to rewatch your favourite film, reread your favourite book or replay you favourite game, knowledge of the lore will change that experience, like you are experiencing it for the first time once more. Or – if you’re struggling for something to write – create some lore for an entirely new world no matter how stupid or over the top, and see what you can pull out of the fictional haven. Hey, maybe you’ll be the next person to add a new monstrosity to the Lovecraftian mythos, or the next person to be working on Jedi history; or maybe you’ll be part of the lore community next time there’s a huge discovery on Destiny or a big reveal from CD Projekt Red.

Ok so I’ve read most of this but obviously I don’t really understand a lot as I don’t play these games