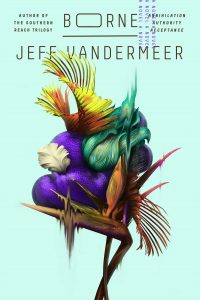

Borne by Jeff VanderMeer – Book Review

Today, Mord had tried to kill us by crushing us under his tread. Today, he was several stories tall and a monster. Wick was grappling with this, with the shock as much as I was, the wrenching dislocation of trying to make two separate worlds match up, the one that was normal and the one that was grotesque, the old and the new – the struggle to make the mundane and the impossible coexist just as it seemed impossible I had ever trailed my fingers through the water of a pond to let the little fish nibble or watched mudskippers through a school-yard fence or eaten at a fancy restaurant.

Following the success of his Southern Reach Trilogy (2014), Jeff VanderMeer changed tack again. Rather than repeating his previous efforts, Borne (2017) breaks new ground, as a bizarre, frightening and wonderful mixture of biotech, post apocalypse, the Weird and the surreal. Borne draws on much of the same concerns as the Southern Reach novels, particularly the Anthropocene, humanity’s destructive relationship with our environment, attempts at communication between the human and the nonhuman. However, Borne lets the nonhuman talk back to us.

Following the success of his Southern Reach Trilogy (2014), Jeff VanderMeer changed tack again. Rather than repeating his previous efforts, Borne (2017) breaks new ground, as a bizarre, frightening and wonderful mixture of biotech, post apocalypse, the Weird and the surreal. Borne draws on much of the same concerns as the Southern Reach novels, particularly the Anthropocene, humanity’s destructive relationship with our environment, attempts at communication between the human and the nonhuman. However, Borne lets the nonhuman talk back to us.

Borne is set in a ruined, postapocalyptic city, known only as the City, which has been bled dry and destroyed by the Company and their out-of-control biotech experiments. The City lives under the shadow of Mord, a giant flying bear with an insatiable bloodlust who is only the worst of the Company’s many experiments gone wrong. Rachel, a refugee from an island destroyed by climate change, ekes out an existence as a scavenger in this polluted, transfigured landscape, living in the deserted Balcony Cliffs with her partner Wick, a dealer in psychotropic biotech. One day whilst out scavenging she finds a strange creature embedded in Mord’s fur, which she takes home and names Borne. At first, Rachel and Wick are unsure whether Borne is a plant, animal or another piece of rogue biotech. However it quickly becomes apparent as Borne grows and becomes able to communicate that he is much more than any of those.

Borne himself is a wonderful creation at the centre of this novel, an original, intriguing and charismatic being destined for the pantheon of SF’s great depictions of the posthuman Other. Originally shaped like a vase with tentacles coming out the top and a variable number of eyes, his bizarreness is compounded by his ability to change shape, expand, and to absorb other beings. Borne is instantly charming. VanderMeer manages to imbue him with personality from the start, and his relationship with Rachel, a particularly fraught parent/child dynamic, forms much of the heart of the book. Rachel and Borne’s attempts to communicate across their wildly divergent life experiences and worldviews form a strand throughout the whole story. The games Borne plays with language, punning and experimenting with linguistics and words, are delightful and fun but also push the English language to its limits – how can we communicate when we are stuck trying to nail down our subjective experiences with words and hope those words convey the same meaning to the listener? Because Borne is charming and talks back to us, Rachel and the audience are lulled into a false sense of security – Borne’s anxieties that he has been created as a weapon prove to be well founded, and his and Rachel’s failure to communicate has consequences far direr than the strain it puts on their relationship.

VanderMeer excels at creating landscapes full of the strange and uncanny that nevertheless he renders as thoroughly believable and lived-in. The incredible sense of place that makes the Southern Reach trilogy so striking is also present here. VanderMeer deftly avoids many of the cliches of the post-apocalyptic, in favour of his own uncanny vision. Hence we get an unforgettable landscape, a toxic, polluted and ravaged wreck at the end of the world that achieves its own kind of shattered beauty. VanderMeer’s wasteland is populated with discarded biotech that has gained sentience and merged with the surviving wildlife, feral children who have been bioengineered into monsters, apocalyptic death cults who worship the giant flying bear, and outlandish characters like the Magician, who used to work for the Company but has gone rogue and is trying to wrestle power away from Mord. VanderMeer’s incredible talent is making this all work, not just in the context of the story itself, but in terms of the book’s wider context of anxiety about the Anthropocene, climate change and the destruction of the planet. For VanderMeer, the Weird and the uncanny stem from the disconnect between the world as we currently understand it, and the nightmare of destruction and annihilation we are creating for ourselves and the living beings we share the planet with but refuse to acknowledge. The transition across this gap is a source of existential horror that throws the entire way we understand and perceive reality into question, a feeling everyone living through the Covid epidemic of 2020 will no doubt recognise.

Borne is an impressively complex novel with a complicated relationship to genre. In its use of archetypes it draws from Fantasy as much as SF, yet its fascination with humanity, the posthuman, and what it means to be a person, places it firmly in the tradition of science fiction all the way back to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. The character of Borne is so strange and alien that he manages to direct the reader’s attention away from the assumptions that Rachel has made about others in her life and the way she relates to them simply because they appear more human. Underneath the bland facelessness of the Company hides something much darker and more disturbing, a colonialist hunger to exploit the world, use it up and spit it out. Even the foxes who follow Borne around out of curiosity wind up having more agency than Rachel expects, something expanded on more in Borne’s wonderful and confounding sequel Dead Astronauts (2019). Jonathan reviews Jeff VanderMeer’s Borne: “Ultimately, Borne is a book both fascinating and disturbing, one whose questions about humanity and the way we interact with the nonhuman will resonate in the reader’s brain for years to come.”