TOWER by Bae Myung-hoon, translated by Sung Ryu (BOOK REVIEW)

“A little bit of civilization and barbarism go hand in hand in any society. When the power of the civilized world drives an individual to desperation, they resist by resorting to barbaric violence more often than you might expect.”

Bae Myung-hoon is a South Korean science fiction writer, and Tower (written in 2009 but translated into English by Sung Ryu and published by Honford Star in 2021) is his first novel to be translated into English. Bae is hugely popular in South Korea, where he has won both literary and science fiction awards, and on the basis of Tower I very much hope we see more of his work published in English soon. Tower is a mosaic novel set in Beanstalk, a 674-story, 500,000 resident population, 65-year-old skyscraper that is its own sovereign nation. Across six linked short stories, plus three in the Appendix which take the form of stories, interviews or documents written by characters in the previous stories, we get a picture of life in Beanstalk, and how the lives of the tower’s residents are shaped by the forces of power that shape modern life. SF readers may be put in mind of J. G. Ballard’s masterful dystopia High Rise (1975) from the concept of the book alone, and Bae does have a sharp eye for satire, particularly at the expense of the government, the military and those who would try to keep order. However Bae is a far less nihilistic writer than Ballard, favouring instead a witty absurdism reminiscent of Stanisław Lem, Kurt Vonnegut or Robert Sheckley. Thus, while these stories tell us something amusing and cynical and frequently sad about modern life, they do so with admirable warmth and heart.

Bae Myung-hoon is a South Korean science fiction writer, and Tower (written in 2009 but translated into English by Sung Ryu and published by Honford Star in 2021) is his first novel to be translated into English. Bae is hugely popular in South Korea, where he has won both literary and science fiction awards, and on the basis of Tower I very much hope we see more of his work published in English soon. Tower is a mosaic novel set in Beanstalk, a 674-story, 500,000 resident population, 65-year-old skyscraper that is its own sovereign nation. Across six linked short stories, plus three in the Appendix which take the form of stories, interviews or documents written by characters in the previous stories, we get a picture of life in Beanstalk, and how the lives of the tower’s residents are shaped by the forces of power that shape modern life. SF readers may be put in mind of J. G. Ballard’s masterful dystopia High Rise (1975) from the concept of the book alone, and Bae does have a sharp eye for satire, particularly at the expense of the government, the military and those who would try to keep order. However Bae is a far less nihilistic writer than Ballard, favouring instead a witty absurdism reminiscent of Stanisław Lem, Kurt Vonnegut or Robert Sheckley. Thus, while these stories tell us something amusing and cynical and frequently sad about modern life, they do so with admirable warmth and heart.

Tower shows us a picture of the larger-than-life Beanstalk, a massive high rise building likened to the Tower of Babel by its detractors and named after a fairy-tale. Bae engages in exactly the kind of world-building that is my favourite – we get details of how Beanstalk works slowly leaked out across the stories, and we come to understand it as a physical place, a neighbourhood and a political entity through the lives of its residents. We come to learn how Beanstalk’s national border is situated on Level 22, about Beanstalk’s citizen-run free mail delivery service and labyrinthine elevator system, about Beanstalk’s rivalry with Cosmomafia, a militant group with links to the former Soviet Union who threaten all out war on the tower. But all of this is in the backdrop. The stories themselves focus on everyday people living their lives within the madness that is Beanstalk.

‘Three Wise Recruits’ focuses on three postdocs who are hired by Beanstalk Tacit Power Research to map out the webs of power and influence within the building, who discover that a major power broker in Beanstalk’s social and political economy is a dog. ‘In Praise of Nature’ tells the story of Writer K, an author with terraphobia – a common condition in Beanstalk residents, where a fear of being on the ground prevents them from ever leaving the building – who gives up the political, polemical work of his youth to become a nature writer. ‘Taklamakan Misdelivery’ features a woman harnessing community power and the internet to help rescue a downed fighter pilot she used to date. ‘The Elevator Manoeuvre Exercise’ is a government transport official’s account of how Beanstalk’s elevator network is disrupted by the rivalry between the working-class horizontalists and the elitist verticalists. In ‘The Buddha of the Square’, an immigrant to Beanstalk joins the Beanstalk Security Guardhouse and finds himself put in charge of a gentle elephant brought in to quell protests. And in ‘Fully-Compliant’, Choi Sinhak, a long-suffering officer in the Intelligence Bureau, tries to stop a Cosmomafian plot to destroy Beanstalk with little to no help from his superiors.

These descriptions should give some idea of the absurdism of Bae’s off-beat humour. It doesn’t convey quite how cleverly constructed these tales are, or the depth of their social and political impact. ‘In Praise of Nature’ grapples with the problem of artistic expression under power. Writer K is faced with the difficulty of criticising the current regime when he knows the personal consequences will be disastrous for himself, but what point does his art have if it refuses to engage with the social reality K finds himself in? ‘The Buddha of the Square’ satirises all police forces that would attack the people they are sworn to protect, whilst ‘Fully-Compliant’ criticises government bodies’ unwillingness to act even when it may save lives. Throughout, Bae critiques the bureaucratic ridiculousness of government and exposes the pompousness of self-important, self-serving politicians. It is appropriate that we are introduced to the tower through Beanstalk Tacit Power Research, as Bae is largely concerned with the unexpected ways in which governmental and bureaucratic power shapes everyday people’s lives. At times, one is reminded of Franz Kafka’s The Trial (1925) or Terry Gilliam’s film Brazil (1985) in the way people’s lives and concerns are swept aside by the impersonal machineries of bureaucracy.

However, Bae is possessed of a warmth, humanity and optimism lacking from the likes of Kafka’s grim vision. Underlying all these stories is the implication that, for all its faults, for all that Beanstalk epitomizes the excesses and alienation of late-period capitalism, people still find a way to build communities. This is a major theme in ‘Taklamakan Misdelivery’, not just in the postal service which runs entirely on people’s goodwill, but in the attempt to recover the missing pilot, which is achieved thanks to everyone in the tower chipping in and helping with the search, thus providing the staggering manhours necessary to search a satellite photo of a desert. Similarly, in ‘Fully-Compliant’, the Cosmomafian plot depends on the detonation of bombs which have been planted in Beanstalk during its construction, but the people who live in the houses that hide the bombs all individually make the choice to disarm the bomb because they cannot bare the thought of destroying their own neighbourhood. However dehumanising and deranged their surroundings, the citizens of Beanstalk can’t help but form communities as part of the natural process of living with other human beings.

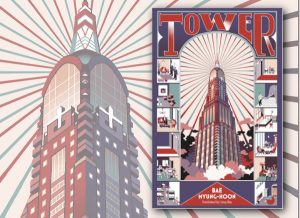

Tower is both a sharp and incisive satire on modern life and a reflection on the things that keep us human even in the most dehumanising settings. Bae’s writing, expertly translated by Sung Ryu, is perfectly able to convey both the most absurd humour and the real human pathos, frequently in the same situation and in the same paragraph. The end result is a novel that is funny and thought-provoking in equal measure. Honford Star have done a wonderful job with this book, extending to the cover art, where Jisu Choi’s gorgeous illustration shows subtle details from each story. I can only hope that this will lead to more of Bae’s work being published in English, and more South Korean science fiction in general finding its ways to our shores.