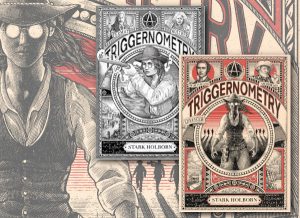

TRIGGERNOMETRY and ADVANCED TRIGGERNOMETRY by Stark Holborn (BOOK REVIEW)

The novella/short novel format seems to have a natural affinity for tales of the wild west from my early school experience reading Shane (38,000 words) by Jack Shaefer to True Grit (55,000 words) by Charles Portis. In combination Stark Holborn’s two Triggernometry stories of mad Malago Browne the renegade frontier mathematician might still fall short of Shaefer’s word count, but that doesn’t in anyway stop them from packing a very satisfying double-barrelled narrative punch. The fact that each one could be consumed in just a couple of hours is a positive advantage in a world where time is in perennially short supply.

The Wild West of late nineteenth century America has been an inspiration for films and novels since the birth of the dime novels and the early motion pictures. Their prevalence is perhaps the result of the navel gazing cultural fascination that American society had with this aspect of their history, combined with the global economic might of the Hollywood film industry. Nonetheless, authors and film makers have played in many different ways with the form, for the conventions of genre are as much a temptation as a rulebook to the creatively minded.

The Wild West of late nineteenth century America has been an inspiration for films and novels since the birth of the dime novels and the early motion pictures. Their prevalence is perhaps the result of the navel gazing cultural fascination that American society had with this aspect of their history, combined with the global economic might of the Hollywood film industry. Nonetheless, authors and film makers have played in many different ways with the form, for the conventions of genre are as much a temptation as a rulebook to the creatively minded.

Where The Wild Wild West mixed gunslingers and technology, and Dave Atwell’s The Rotting Frontier mixed gunslingers and zombies, Holborn boldly combines gun-(and other object)-slingers with mathematicians.

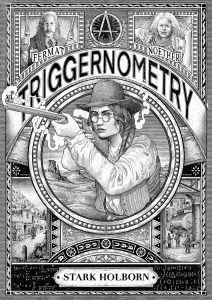

Holborn’s speculative novum doesn’t quite fit the genres of steam-punk magic or zombie horror. Instead it feels like a merging of Attwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Jemsin’s The Fifth Season. In Triggernometry though, it is neither women nor plate tectonic wizards who are marginalised, exploited and hunted but mathematicians. At some point before the story’s opening but within recent memory – a bit like the dawning of Attwood’s Gilead – a new power the Capitol has taken over America. Teaching or practice of mathematics has been made illegal (along with the use of Latin!). In an anti-intellectualism that has echoes of the Khymer Rouge in Cambodia, the simple wearing of spectacles is such a confession of academic pretensions as to prompt instant arrest. This is a problem for Holborn’s myopic first-person protagonist Malago Browne, previously a learned professor of trigonometry, who needs her glasses.

Of course, the Capitol’s mistake is totally underestimating just how badass a set of mathematicians can be. I mean it was the sums of mathematicians that landed men on the moon and Perseverance on Mars; the calculation of trajectories, projectile velocities and angles makes Browne a master of trick shots, while her companion Ferm (Pierre Fermat) navigates the world of chance and probability such that odds of ten to one are as nothing to our intrepid pair. Of course, a world that has abandoned maths and made arithmetic a crime will encounter – shall we say – some accounting difficulties. Browne and Fermat get by on an alternating strategy of offering a black-market calculations service and just – dammit – robbing people.

Of course, the Capitol’s mistake is totally underestimating just how badass a set of mathematicians can be. I mean it was the sums of mathematicians that landed men on the moon and Perseverance on Mars; the calculation of trajectories, projectile velocities and angles makes Browne a master of trick shots, while her companion Ferm (Pierre Fermat) navigates the world of chance and probability such that odds of ten to one are as nothing to our intrepid pair. Of course, a world that has abandoned maths and made arithmetic a crime will encounter – shall we say – some accounting difficulties. Browne and Fermat get by on an alternating strategy of offering a black-market calculations service and just – dammit – robbing people.

Holborn embraces her mathematical aesthetic as fulsomely as Will Self embraced the London cabbie culture in The Book of Dave. The kind of oxford set of compass and set squares so beloved of school children for the first day of term (and yet dispersed into the ether by the end of the first week) in Triggernometry become venerated artefacts. However, these are not simply instruments of maths instruction, but weapons of mass destruction. In the hands of Browne and her allies, pointed set squares, scything protractors and sharp-edged rulers become lethal instruments wielded in hand to hand combat with as much disarming and impaling skill as any Klingon ever swung a bat’leth.

The chapter headings and the prose make frequent punning riffs on mathematical notation and concepts. While most of the references flew higher than my A-Level maths could reach – they did not need to be understood to be appreciated. For example, when Browne meets an old friend.

The most dangerous mathematician in all of the Western States bared her teeth in a smile, lifting her hands to signal a message. (5,4),(11,5),(71,7).

I smiled bleakly. No tears, no embraces, no recriminations. Just a series of Brown numbers. I wouldn’t have expected anything less.

‘Good to see you too,’ I said.

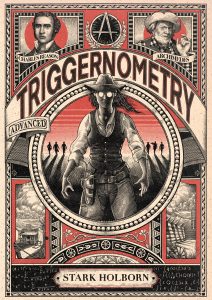

Then there are the mathematicians. Holbrook populates her story with names plucked from the halls of mathematical fame, their particular combat skill sets aligned with the research specialty of their namesakes. Thus Pierre Fermat – a name most famous for the mislaid* proof of his enigmatic last theorem – is the custodian of statistics and probability. Browne herself is named for Marjorie Lee Browne a pioneer of maths education for whom the authoritarian suppression of the Capitol would have been an anathema. I had a personal reason for appreciating the mention of Ada Lovelace, though I was disappointed she only appeared on wanted posters rather than in person. As a senior school leader I once suggested we named one of the “Houses” in our Maths & Sports specialist college after Lovelace in her honour. However, my boss thought the parents and pupils more likely to associate the house name with Linda Lovelace, a famous 1970s adult film star, and I had to bow to his superior experience in such matters.

(Ada Lovelace – source Ada Lovelace Day 2019 (spartaglobal.com))

Both books are sprinkled with appearances by different eminent mathematicians, translating their numerical, statistical or topological genius into explosive combat potential. However, persecution has left its mark. When Browne arrives in the mathematicians’ version of a prohibition era speakeasy, sequestered away behind a backroom door, she finds the mathmos drowning their sorrows in distractions more euclidean than epicurean.

Some turned immediately back to scrawling theroems on the walls, others to vicious games of chance, their pupils as small as multiplication dots.

The two stories are short but still pack a decent narrative punch, full of twists and turns as different solutions are presented and then proven to be imaginary, until the plot function eventually collapses to a singularity.

Triggernometry

In their opening outing Fermat and Browne reminded me of Alias Smith and Jones, a TV show from my youth. This had two western outlaws Hannibal Heyes and Kid Curry trying to abandon their life of crime and seek rehabilitation by securing an amnesty from the Governor. However, they had to carry out favours along the way and each episode was a different mission requiring tact, diplomacy and sheer gunslinging skill, as they inched their way in the course of three series towards civilian rehabilitation and sanctuary.

(Alias Smith and Jones – source westernfictioneers.blogspot.com)

In Triggernometry, tired of their dangerous double life and with few friends to count on, Fermat and Browne are lured into doing a favour for a shady politician that could guarantee them enough money to fund a safe retirement over the border.

Advanced Triggernometry

Some five years after the conclusion to Triggernometry, Browne and Fermat have parted ways, but Browne is tempted out of scholarly retirement by a deputation from a village under threat from a vindictive Capitol favoured robber baron. The plot unashamedly pulls on the mantle of The Magnificent Seven, as Browne assembles a disparate desperate band of talented mathmos – including one particularly eminent Greek – as they aim to face down odds of – well about 100:7 now you come to mention it. However, as the band quickly discuss

“We’ve faced worse odds.”

“Seven is a gaussian prime.”

“And a lucky one.”

“And a double Mersenne!”

“Can’t think of a better number.”

Now you didn’t get that kind of insight from Yul Brynner did you!

(The Magnificent Seven – source gonewiththetwins.com)

However, in these two books Holborn does more than take the genre off on an engaging tangent through the reworking of some classical western plots. There is a terse elegance to the prose that had me reaching for the highlight function of my kindle more often than I have in many much longer books. The cumulative frequency of “lols” and “nice lines” was very impressive, of which the following are only a subset.

“A beam of light broke the dark open, an oil lantern, smeared with tar to make it secret. It showed us half an inch of face, skin like greasepaper used too many times and a thread of colourless hair.”

“All I had to do was follow the railroad as it cut its way across the empty plain; two rusted rails and crumbling cottonwood sleepers, the corroded artery that kept these towns alive.”

“Beside them stood what looked like a jumble of derelict buildings, tethered to the sky by a thin thread of smoke.”

“Clang. Across the plain a lonely, lead-tongued church bell began to call out noon.”

“A cobbled-together printing press dominated the space, like some huge, raw-boned beast. It smelled like pencil shavings and wet ink and clean paper; scents that dragged a pang of longing from my chest.”

“We rode into Summerville under a bad sky, bloody as a nail cut to the quick.”

There is too this line that put me in mind of the inexorable and apparently irreversible shift in contemporary society’s Overton window when Browne contemplated how her world has changed enough to make her a hunted outlaw.

“I looked down at my hands, remembering the headlines, the creeping awful way in which the things we had laughed at and dismissed as lunacy became reality.”

The last time I saw a left-field idea work so brilliantly was Daniel Polansky’s The Builders, another team of mismatched egos on a mission of vengeance, only Polanksy had animals rather than mathematicians delivering what amounted to a Quentin Tarantino version of Wind in the Willows. In Triggernometry and Advanced Triggernometry, Holborn has taken another inspired concept forward, with fast paced plotting, compelling characters and dazzling prose.

*The proof of Fermat’s last theorem was mislaid, but briefly retrieved by Lisbeth Salander in The Girl Who Played with Fire – second of Stieg Larsson’s Millenium Series about The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.