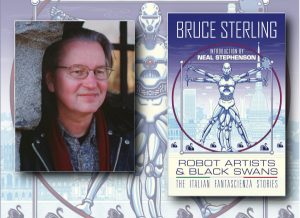

Interview with Bruce Sterling (ROBOT ARTISTS AND BLACK SWANS)

Bruce Sterling helped to define cyberpunk when he edited the anthology Mirrorshades in 1986, and wrote some of the genres defining texts such as Schismatrix (1985) and the Campbell Award winning Islands In The Net (1988). He coined the term ‘slipstream’ in 1989, and in 1990 wrote the iconic steampunk alternate history The Difference Engine with fellow cyberpunk pioneer William Gibson. His novel Distraction (1998) won the Clarke Award, and his novelettes Bicycle Repair Man (1997) and Taklamakan (1999) have won the Hugo Award. He edited the science fiction critical fanzine Cheap Truth and has since written nonfiction for magazines such as Wired, SF Eye and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. Since 2007 he has lived in Turin, Italy. Tachyon Publications is releasing the collection Robot Artists And Black Swans, short stories written by Sterling as by his Italian alter ego Bruno Argento, in early 2021.

Sterling was kind enough to talk to The Fantasy Hive via Skype in November 2020.

Your latest collection, Robot Artists And Black Swans, is coming out with Tachyon [next year] on 27th April 2021, would you be able to tell us a little bit about it?

That’s a kind of an interesting cultural artefact, because I’ve been spending a lot of time here in Italy. I soon realized that I wanted to write about Italy, but it struck me as kind of tedious to write an endless series of Americans in Italy stories. There are a lot of Americans in Italy, but they’re actually the least interesting people. So I thought, what would I write if I was an Italian science fiction writer? That actually seemed a lot more interesting. I’ll just pretend I’m Italian and write what I want to write about. That seemed to help.

So I made up a pen name (but I don’t really use it that much). He’s Bruno Argento, the Turinese science fiction writer. But nobody’s fooled by that pretence except me. When I write Bruno Argento on a story, I know that I’m going to write from an Italian perspective. It’ll be set in Italy, all the characters will be Italian. And it’ll be written in English because I don’t write literary Italian. I’m not good enough to be an actual Italian writer! But luckily, my wife’s a literary translator. So I’ve got in-house Italian on tap. I write nonfiction columns for magazines in the Italian press. I have a column in the local newspaper. I wrote for Wired Italia and design magazines. I was also writing for the Italian science fiction press, which isn’t real big but it does exist. So I have books out in Italian that have sort of no English language equivalent, they’re Bruce Sterling collections that just don’t appear in English.

But this one, Robot Artists And Black Swans, actually is a Bruce Sterling collection, which is appearing in English, but it’s all Italian. People are asking, well, is it sci fi, is it fantasy? It’s both science fiction and fantasy. It has got a lot of historical fantasy, a lot of futuristic stuff. Even things that might be construed as cyberpunk on occasion. But it’s actually about Italy. It’s just about the fantastic aspects of Italy. And I’ve done a bunch of them. They’re some of my better work actually. It’s quite a challenge to write from a foreign perspective, but I find it refreshing and it keeps me from tediously repeating myself.

But this one, Robot Artists And Black Swans, actually is a Bruce Sterling collection, which is appearing in English, but it’s all Italian. People are asking, well, is it sci fi, is it fantasy? It’s both science fiction and fantasy. It has got a lot of historical fantasy, a lot of futuristic stuff. Even things that might be construed as cyberpunk on occasion. But it’s actually about Italy. It’s just about the fantastic aspects of Italy. And I’ve done a bunch of them. They’re some of my better work actually. It’s quite a challenge to write from a foreign perspective, but I find it refreshing and it keeps me from tediously repeating myself.

Then I have the major project of Bruno Argento’s first novel, which is this epic historical fantasy I’ve been working on for years. I work on it by fits and starts. I had a pretty good head of steam before the pandemic started getting hot and heavy. You’d think you’d be able to spend a lot of time on a novel when you can’t leave the house. But in point of fact, that didn’t prove to be true. During the pandemic, I’ve done a lot of occasional writing. I’m very heavy in social media doing a lot of weird stuff. But I’ve kind of had to put that big novel project in abeyance, but I hope to pick it up again. It’s not like it’s under deadline or that anybody’s clamouring to read it. And it is very large and ambitious. It’s kind of a Neal Stephenson sized historical blockbuster book. So yeah, that’s Bruno’s career.

I still write other science fiction that’s just my own English language style stuff. But this is a particular cultural experiment of mine. Because I can actually hang out with fantascienza people and publish in fantascienza magazines, and be accepted as a contributor in the Italian science fiction world. Which is not huge, but it’s a good size, because Italy’s a G7 country. And there aren’t a lot of people here who are full time science fiction writers, but there are people here who are science fiction people and celebrities. Like Licia Troisi is a fantasy novelist. And she’s also a television personality and an astrophysicist. So, you hang out with Licia, you’re kind of into an interesting cultural scene. And I know a lot of Italian technology and technology art people. People with Arduino are there in the tech art scene and they’re writing for Wired. Like Dario Tonani, who wrote the afterword to my book. He’s a millennial novelist, but he’s also a pop science writer.

When you’re hanging out with them, you’re actually kind of engaged to the world of Italian tech development. And tech speculation. And then there’s also big events like Lucca Comics and Games, which is just your basic European fandom event, but really big and super Italian. They’re into comics and costume play, they like design a lot. Italian sci fi fans are really into pretty clothes! Then there’s a big fantasy cinema contingent like Triesta’s Science+Fiction. I tend to go there every year, and I’m even a judge for this. So I’m really not much of a cinema guy, but I am kind of an Italian cinema guy. I find that expands my horizons a little. It really kind of breaks the tedium. I would say quite frankly that as an Italian science fiction writer, I’m not really a very important Italian science fiction writer. I’m a mid range Italian science fiction writer. I write like, maybe one story a year, and they’re kind of eccentric.

This split between Bruce Sterling and Bruno Argento really interests me. When you start to write a story, is it a very conscious decision to choose which one you’re going to be?

Yeah, it is. I know that when I’m doing Argento, I’m doing something from an Italian national perspective. There’s also a lot of in-jokes. Most of them are deliberately written for an Italian fantasy audience. So there’s a lot of insider name dropping. There’s a group of Roman fantasy fans who are called the Connectivists, they’ve been known to commission me to write stuff for their Connectivist group. I consider Bruno to be a kind of Turinese Connectivist. We’re following the Connectivistd on social media, so when I write Connectivist stories, they’re very into issues like artificial intelligence, networking, cyberspace and virtual realities. And Rome, because they’re mostly Roman. So I’m actually imitating them. And I was like, I’m part of a movement, the Italian equivalents of cyber punks. It’s interesting to be in Italian science fiction and following a particular line of development.

Then there’s a lot of other stuff I do, which is kind of based on other forms of Italian fantasy writing, like Calvino. I’m writing Calvino pastiches, or things in which Calvino’s ideas are referenced. I know Italians know that because they worship the guy. He is a big deal for them. And he also spent a lot of time here in Turin. So he kind of casts a big shadow. The Italo Calvino library is like 500 meters over that way. I’ve been known to go over there with a laptop and do a little bit of composition work. I enjoy this opportunity to really take on the local flavor. And play up to a local audience.

Then there’s a lot of other stuff I do, which is kind of based on other forms of Italian fantasy writing, like Calvino. I’m writing Calvino pastiches, or things in which Calvino’s ideas are referenced. I know Italians know that because they worship the guy. He is a big deal for them. And he also spent a lot of time here in Turin. So he kind of casts a big shadow. The Italo Calvino library is like 500 meters over that way. I’ve been known to go over there with a laptop and do a little bit of composition work. I enjoy this opportunity to really take on the local flavor. And play up to a local audience.

I’m not writing Italian science fiction in order to make Americans understand what Italy is. I’m actually writing Italian science fiction that’s trying to do what I think Italian science fiction ought to be doing. I’m trying to contribute to the discourse. But not by saying, I’m the American sci fi guy here to tell you how to do it. On the contrary, it’s like I’m American sci fi guy here to learn what you’re doing and extend it. It’s not like this splits me in half in any way. Because in point of fact it’s more like I’m split in four because I am from Austin, but I spent a lot of time in Belgrade. And lately, I’ve been spending a lot of time in Spain, but I’ve been in Turin long enough. I have enough friends here and I’m into the scene enough that I can do Bruno Argento in Belgrade, no problem. Sometimes I’m better at being Bruno Argento when I’m not in Turin!

It sounds like you’ve really absorbed the Italian culture and history, which really comes through in the stories. Does that involve a lot of research?

Yeah, but I am a journalist. So that kind of comes naturally to me. And also, I really enjoy reading old texts. I’m something of an antiquarian! I like to read stuff that’s 300 or 400 years old. Stuff like The Decameron has a lot of interest for me. I read it from a science fiction perspective, or kind of a media studies perspective. Because if you look at The Decameron, it’s basically a whole bunch of horror stories, but it’s like ten people talking to each other. They’re all trading yarns. So it’s kind of very meme-like. The way the way it’s put together is pre-novelistic. It doesn’t really have a plot yet, but it has a very network connected social media thing going on. Because the stories are very short, and they’re like set in different places. They’ll have kind of punch lines, and they’re thematically related, and a lot of them are really old because they’re basically folk tales. I find that of huge interest. It’s like, Okay, how did he assemble this? What was he trying to do? This is like something that you could do in the modern day, maybe do it on a network or something?

So, there are a lot of things in Italy that I find of intense interest. But there’s also strange gaps. I would never want to write a modern Italian realistic novel or story, because I just don’t understand them well enough. But I can write about them 100 years ago, or 200 years in the future! I actually think that my distance from the society produces a better work, because I don’t get bogged down in the tall weeds. Nobody in Italy mistakes me for an Italian writer. And the stuff that I do, they understand that it’s fantascienza, in that it’s very fantascienza influenced. But Bruno Argento by Italian standards is really a pretty strange guy. He’s like he’s the only science fiction working sci fi writer in modern Turin for one thing. But also, he just writes from a really strange perspective. He’s just writing about Italy, but he’s writing about aspects of Italian society that most Italians don’t write about. It doesn’t have the clichés of Americans writing about Italy, but it also doesn’t have the clichés of Italians writing about Italy. It’s sort of like Italy is somehow talking to itself. But they read it, God bless them. They’re commissioning it even when I’m a modestly successful Italian science fiction writer. If I if I ever get my book done, maybe I’ll be worthy of more notice.

Bruce Sterling was actually rather well regarded by Italians. This is one of my big overseas markets as an American writer. I have a lot of books in Italy that people still read. But this is like a new experiment. The stuff that I write in Italy just doesn’t sound much like the other stuff. It’s really, really about Italy. It’s like really kind of struggling to make it come alive on the page. Whereas these other cyberpunk things are all stuff like virtual reality or heavy weather or cyber war skulduggery or whatever us cyberpunks are into this week! So I’m kind of wondering if there’s an exit strategy – is there a day when I’m going to leave Italy and stop being Bruno Argento? But I don’t really have many reasons to leave. I’ve got an apartment here in Turin, and I’m not acculturated, but pretty cosy here. It’s not such a bad place.

Bruce Sterling was actually rather well regarded by Italians. This is one of my big overseas markets as an American writer. I have a lot of books in Italy that people still read. But this is like a new experiment. The stuff that I write in Italy just doesn’t sound much like the other stuff. It’s really, really about Italy. It’s like really kind of struggling to make it come alive on the page. Whereas these other cyberpunk things are all stuff like virtual reality or heavy weather or cyber war skulduggery or whatever us cyberpunks are into this week! So I’m kind of wondering if there’s an exit strategy – is there a day when I’m going to leave Italy and stop being Bruno Argento? But I don’t really have many reasons to leave. I’ve got an apartment here in Turin, and I’m not acculturated, but pretty cosy here. It’s not such a bad place.

I wander a little less than I did, but I have very globalist tendencies. I don’t have much trouble living out of a suitcase. I was able to do that for years on end, both as a teenager and as an adult. I always felt like my position on the planet surface was arbitrary. I learned a lot from Brian Aldiss, who was one of my mentors. He told me early on that there were too many science fiction writers who could write about Mars, but they have nothing useful to say about Indonesia. I really took that advice of his to heart. And of course, he was a world traveller. He was in World War Two. And he was in uniform in Indonesia. But he also travelled a lot in Europe. He did a lot of travel, writing about Yugoslavia and these other kinds of things. He spent a lot of time in Italy. He’s kind of a globetrotter guy, and he’s one of the founders of world SF, the early global science fiction writer group.

I really learned a lot from Brian’s attitude. It’s like, I could be like an Austin Regional writer, and write a lot of sci fi about Texas, because that’s pretty entertaining. Joe Lansdale, for instance, as a Texas writer, he’s extremely popular in Italy. Joe Lansdale has a very high literary reputation here. They really, really like his regional Texan writing in Italy. But I was kind of taking Brian’s point. And you know what he’s really saying, is your head big enough? If you can imagine a Martian, you ought to be able to imagine an Indonesian. And in fact, imagining an Indonesian will enable you to imagine a much better Martian. So yeah, I just did a lot of road work. And ideally, I would like to write a regional novel about the planet Earth. That’s kind of a big topic. But I think I proved that I can actually write regional fiction about somebody else’s region. And that’s kind of a step toward this very cosmopolitan science fiction. Instead of just going into the past or into the future, it goes cross culturally.

Your earlier stuff is still very much associated with cyberpunk because of your huge involvement with setting up the boundaries of the genre originally. It’s sort of become a cliché to say that we live in the cyberpunk present, but we live in a world with the internet and social media. And you can see very clearly the effect that the internet has on the real world, right?

Yeah. We’re even into the Post internet now.

So how do you feel about your legacy as a cyberpunk all these years later, now that we’re almost living in that reality?

It’s an interesting question, because Punk is a very old fashioned idea. It was a useful method, and it was a big deal in 1977. Which was quite a long time ago. And cyber is also kind of long in the tooth. It’s not an exotic minority activity. I mean, these are the biggest companies; Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, are the industrial titans of the day. So you know, it’s like being a guy hanging out in the Old West and writing about the railroads coming. And now the railroads have become a really big industry. So it’s like, so you know, Mr. Electronic Cowboy of the Electronic Frontier, how do you feel about it now that it’s covered with the big town? And sure, if you’re a pioneer, and you don’t get an arrow in your back, eventually everybody’s gonna pat you on the head and call you old timer. And that’s a legitimate thing to call you. Because it really is old fashioned, right?

So things like Cyberpunk 2077 are very retro in tone. They’re literally remaking an arthouse Korean game from the 80s. And ramping it up with better interior design. It’s these Eastern European game developers who have adopted this stuff, and in a very knowing way. They don’t consider it new in any way. On the contrary, they’re anxious to play to the nostalgia market. I don’t really have a problem with that, because I don’t have much trouble playing to the nostalgia market. I understand that game. But it’s also a relief to have this Bruno Argento figure, and it really just isn’t a cyberpunk. I’m using a lot of the techniques of extrapolation, and the stories are constructed as Bruce Sterling stories. But they don’t really come across as something you would have read and Asimov’s in 1987. Being old has drawbacks. But actually knowing how to construct it is quite interesting.

Your problem as a writer of mature years is that you’re very skilful at writing, but you don’t feel much urgency. You don’t really have much that’s new to say. When you’re not anxious to be the voice of your generation, because your generation is fading. You’re not trying to break your way out of obscurity. And you can notice a lot of weird stuff, because you’ve been around a lot. You know what’s weird and what’s not weird. But you don’t really want to dance on the table. It’s not really dignified. So I’m aware of this. And I was always aware of it. What I didn’t want to do is become my own nostalgia writer. I don’t want to write sequels to hits that I had in the 1980s.

Yeah, there’s something just a bit depressing about that!

It’s like a guy being driven down into the coal mine when he’s old and weak. That’s sad. Also, I don’t want to pretend that cyberpunk is a modern development, because it isn’t. I mean Connectivism is more modern than cyberpunk but even Connectivism is 20 years old. So, I watch what young science fiction writers are doing. I tend to look at the trends and so forth. But I don’t go out and argue at them. I’m not an ideologue within the genre. Although I very much was at one point. I was really delivering a lot of sermons about stop doing this and doing that, this is boring, that part’s over. This is the cool new part.

It’s like a guy being driven down into the coal mine when he’s old and weak. That’s sad. Also, I don’t want to pretend that cyberpunk is a modern development, because it isn’t. I mean Connectivism is more modern than cyberpunk but even Connectivism is 20 years old. So, I watch what young science fiction writers are doing. I tend to look at the trends and so forth. But I don’t go out and argue at them. I’m not an ideologue within the genre. Although I very much was at one point. I was really delivering a lot of sermons about stop doing this and doing that, this is boring, that part’s over. This is the cool new part.

I’m not really doing particularly cool new stuff, as an Italian writer, but I am doing stuff that is of cultural interest. And we cyberpunks really wanted to be very global. We were kind of thinly scattered around the world. A lot of us have multinational backgrounds. Cyberpunks tend to marry foreigners for some weird reason! But we hadn’t really lived that life. We were pretending to know all about Istanbul and claiming that we’d been in Chiba city, but we hadn’t really gone there, and like, put on the clothes, eaten the food. So this is a long experiment, but kind of to prove if this is possible. I wouldn’t say that it’s even without risk or problems. Because if you just start to write as if you’re French, the French are gonna take offense. It’s like you’re stealing their marbles. So you kind of have to do it with some tact. But there are guys who do it like this.

There’s an American writer named Jonathan Littell, who’s one of the most important novelists in France right now. And he writes blockbuster French language bestsellers. A lifelong immigrant who just went to France, he thought, well, this is great. I’m going to figure out how to do it. And he did. Like Joseph Conrad. Polish guy in Britain. What’s he going to write about? He’s going to write about British guys from his Polish sea captain perspective. And it turns out to be super interesting. He’s not British, but he’s actually got something to say. He’s a great British writer, who is not British. But what I’ve tried to do is a little subtler, because I’m trying to do it from a genre perspective. And try to encourage other people to do it. These Italians are reading this stuff. And I’m trying to open up things that they themselves could do. Maybe you could describe this topic here or try to follow some of this. I don’t know if it’s successful, but I can say that it’s motivating. When I’m sitting down and writing a Bruno Argento story, I actually feel that I’ve escaped a lot of the difficulties that you’re pointing out there. And they are real difficulties, they could have put an end to my career. I don’t want to be typecast. And I don’t want to repeat myself. But I am also not as energetic and not as ambitious. So I have to find some kind of geographic area there, where I can actually be productive.

You also famously wrote the Slipstream essay. Some of that feels a bit more relevant to the Bruno Argento stories, because you do have a mixture of the fantastic and the everyday, or different genre elements come into play in ways that are unexpected.

Yes, exactly. Or you’re just doing things that are kind of mind boggling. And they have a genre-like sensibility, but they don’t have any of the genre’s tropes. Calvino is very much a core slipstream writer – to the extent that slipstream ever had a core – because he’s somebody who science fiction writers noticed, but he was never one of us. Even though his brother was a scientist, and he was writing stuff like Cosmicomics. Which is all about like the beginning of the universe. It’s almost like a space opera.

Yes, it’s all about science.

Yeah. And he belonged to this group, the Workshop for Potential Literature in Paris. His efforts interest me really a lot like that. I’ve been known to use a lot of Oulipo techniques in my science fiction writing. Without being a big Showboat about it – I don’t write science fiction without the letter ‘e’! But writing as Bruno Argento is kind of an Oulipo game. Because you’re introducing a lot of artificial constraints into the text. I’m writing a sentence, and I go, would Bruno say that? And if the answer is no, then out it goes. It does end up with this kind of strange freshness, or this kind of alienating quality to the prose, which is unusual.

Yeah. And he belonged to this group, the Workshop for Potential Literature in Paris. His efforts interest me really a lot like that. I’ve been known to use a lot of Oulipo techniques in my science fiction writing. Without being a big Showboat about it – I don’t write science fiction without the letter ‘e’! But writing as Bruno Argento is kind of an Oulipo game. Because you’re introducing a lot of artificial constraints into the text. I’m writing a sentence, and I go, would Bruno say that? And if the answer is no, then out it goes. It does end up with this kind of strange freshness, or this kind of alienating quality to the prose, which is unusual.

There’s a story in Robot Artists, which is actually the last one, and it’s about a robot artist. It’s a Connectivist story, and it’s called ‘Robot In Roses’. It’s mostly dialogue between a scientist and an art critic in the 22nd century. But the way that dialogue is put together is really not human. I’ve never written dialogue like that. They spend a lot of their time talking about artificial intelligence, and is it or is it not human, and what does it have to do with human intelligence and so forth? They also kind of talk past each other. It really reads like an Oulipo text. It just doesn’t read like people talking to each other. And now we’ve got these entities like GPT-3, this artificial intelligence that can generate infinite amounts of text. If you train it on a William Gibson training set, it will make William Gibson text. I’ve seen that done and I was sending Gibson versions of this. We wrote The Difference Engine together, which is famously narrated by a computer. So we’re finally into an era here where computers are becoming literary players. And I’m like, Okay, what does this mean?

There’s something going on that the ‘Robot In Roses’ story captures because it’s not confusing or surreal, but it’s like the prose is lubricated. The dialogue has kind of come loose from reality in this case. I’m pretty happy with it because I really feel like it’s very slipstream, and then it’s like super weird. But not in any kind of predictably genre-version of weirdness. It’s weird in a new way. I don’t know where to go with that exactly, except that I am following the compositional experiments in artificial intelligence really a lot.

I’m an art critic here, and I’m a curator and share festival of Electronic Arts. We’re getting a lot of artificial intelligence electronic art now. Some of it is verbal, like bots talking, and some of it’s prose, but a lot of it is visual, or some sonic. There’s a lot of artificial intelligence techno music. So we’re trying to figure out how to be better art critics about work produced with the aid of artificial intelligence. What’s the easy part and what’s the hard part? What’s good and what’s not good? That struggle is starting to inform my fiction in a big way. And especially the Italian stuff, because the Italians take this very seriously indeed. There’s really a lot of art robotics in Italy, oddly enough.

It’s really interesting.

I like to think so yeah, it’s become a career really. I’m here in Turino, and we’re trying to assemble our next SHARE Festival here. And I was like, who’s gonna be the judges? When do we put out our call for entries? This is the 15th or 16th of these festivals we’ve done, and we’re really starting to get on top of our game here. I really like that we’re becoming the regional avant garde in some ways. We really got a veteran set of people. We don’t have a huge budget, but we’ve really been at it quite a lot. Plus Arduino is here, and we get a lot of electronic production stuff.

In Turin, we’re having our P&L of technology tomorrow, and I’ve got to address them. Of course, it’s not a real meeting because of the epidemic. But I’ve got a Zoom. There’s a futurist seed here. These are guys from the local Polytechnic, but they’re really doing this kind of cultural outreach stuff. And I know them and I’m like a keynote speaker for their event. So I’m actually giving them public policy suggestions of like, what should Turino be building now? They’re very keen on smart cities stuff, because they’re actually a high-tech metropolis. They pride themselves on their high tech shops. They’ve got an i3 Artificial Intelligence Centre here, just setting it up. And they’ve got a lot of drone action here because they have an aerospace business. The city council has passed a lot of drone-friendly regulations. They’ll offer venture capital to people and so forth. And I’ve been in Turin long enough that I kind of actually understand what they’re doing. I want to help.

The feedback between the nonfiction work you do and your fiction is a line that’s run throughout your career…

I was trained as a journalist. I knew I had a journalism degree and I thought I would go work for magazines and newspapers, but then I just started writing science fiction novels in college. So I ended up becoming a novelist. Around age 30, I actually started doing rather a lot of nonfiction. And now I do more like consulting. I’m actually kind of in the smoke filled room. It’s like, let’s bring Bruce by here and see what he has to offer! I’m doing that in Beijing and Berlin. And sometimes I used to just go there, but now I just Zoom there. I do travel, and I go to a lot of tech events. And I do a lot of events and meetings that involve non-disclosure agreements. If I think I’m going to learn something, I’ll likely go volunteer. Plus, we do projects here. The wife and I made a house of the future here in Turino and it got funding. Nobody in Belgrade or Austin would ask us to build a house of the future. But the Turanese would. And this was like a project that lasted for five years. And that’s not like a novel, it is a cultural intervention. It’s actually a little hospitality house. It was like an inn almost.

What’s next for Bruce Sterling?

Well, I’d like to finish this Bruno Argento novel. Because that’s kind of a big issue. There are areas that I’m researching that I’ll probably write about. I’m very interested in artificial intelligence, not the old kind, but the post-2014 deep learning. I think I’m starting to get a handle on the limits of what it can do. And that’s actually more interesting than something that has no limits. Now that it’s starting to get some practical applications. I did use SALT, because I know guys who were developing it. And I actually liked it. I can remember what it was like to first use word processing. The Difference Engine is basically a book about word processing in a lot of ways. And I like the idea of doing some AI word processing. I might do some formal science fiction experiments attempting to use AI to like, generate new forms of text.

That’s one of the things that struck me reading ‘Robot In Roses’ is that it’s very much a story informed by how we understand artificial intelligence now, rather than the sort of old traditional conception of artificial intelligence as the huge godlike beings.

Yeah. Well, you know, that’s kind of dated, because that’s the artificial intelligence argument that people were having two years ago. But you know, nevertheless, it interests me a lot to write science fiction about actual technical arguments. I’m also very interested in soft robotics and kinetic art. Because I think they have some deep connection. It’s sort of about giving things autonomy and letting them move, but also controlling how they move. So I’d like to write some kind of critical thing about that, maybe a nonfiction art criticism book. There’s a ton of kinetic art around because it’s really cheap and easy to do. Now, you just buy the actuators and go get your Raspberry Pi. And you can make machines jump through all kinds of hoops. But there’s not a good critical formulation about what’s actually interesting to do. Like, Okay, this is the hard part, and this is the easy part. There’s a place that has a lot of potentiality, and these are just basically desk toys. So I actually spent enough time with that. I’m tempted to do it.

That sounds really interesting.

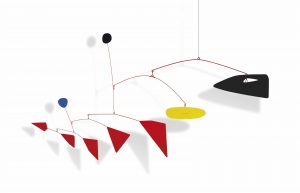

Yeah. It would be a lot of work. I’ve written a lot of nonfiction. I wrote about computer crime and that sort of stuff. But I haven’t really written my master work as an art critic. I read a lot of them. They’re big in Europe, and I spent a lot of time in Europe and I have friends in the art critic world, but I haven’t really made a big contribution there. But I really like kinetic art. And I especially like Calder mobiles. Alexander Calder’s balanced devices made of wire and graphic elements and mechanical elements, and they move around in the breeze.

I’m not familiar with those…

Alexander Calder (1898-1976)

Well, you know you’re in for a treat; you should look up Alexander Calder’s mobiles because they are some of the greatest works of the 20th century, in my opinion, and in the opinion of many others. His prices have held up very well. There’s stuff he banged together in an afternoon that’s selling for a quarter of a million dollars. All the mobiles are very conceptually important. And he’s also like me, he’s an American who spent a lot of time in Europe. He’s an American engineer who got involved in the European art scene. I’ve read his biography, I’m familiar with what he was up to. I think a general assessment of what’s going on in that particular form of art might actually cause an explosion of art development in that area. If you had it all down in a book, and it had more of an O’Reilly book feeling. You could do this, and you could put this on that. And then this part works over here.

It’s like the birth of photography, where at first it’s just a weird curio. Eventually people realize it can be cinema. And then there’s an entirely new artform there, which is now pretty old. Cinema is actually dead right now. I didn’t expect that to happen. But to have the kinetic art thing is kind of easy to do, because robotics is so cheap now. But there’s not really a good sort of cinema critic thing for it, I suppose. There’s not a theory. For like, what’s the part that matters? And what’s the part that’s just a gimmick? So I’m collecting notes for that. I don’t know if I’ll do anything about it or not. But it does keep me awake. And you’re asking me it’s like, what am I doing here? Okay, maybe I’m spinning my wheels. But I’m also just learning a lot of stuff I didn’t know before. I’m trying to arrange it. Not necessarily as a movement, like the cyberpunk movement. But I’m talking to find a creative sensibility for it. Maybe I will, or if I don’t, maybe I’ll know the guy who does. And I can point my finger at him, just say, okay, just go read Cory Doctorow! And that could be very helpful. That’s a good job for a critic. You think you like this – you really like this thing over here!

Thank you for talking with us, Bruce Sterling!