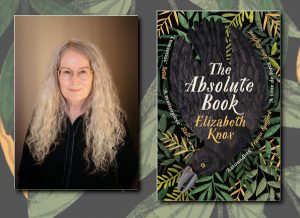

Interview with Elizabeth Knox (THE ABSOLUTE BOOK)

Elizabeth Knox is a Fantasy writer from New Zealand. Her marvellous novel The Absolute Book (2019) is a lyrical work of the Fantastic, involving hidden knowledge, Fairlyand, demons and talking crows, as well as being a powerful exploration of grief. The novel was published originally in New Zealand, and was hailed as an instant classic of the genre. It is published this year in the UK by Michael Joseph and in the US by Viking. She has also written The Vintner’s Luck (1988), a multi-award winning novel about the relationship between a French winemaker and a fallen angel, as well as horror novel Wake (2013), YA series, and novels drawing on her childhood growing up in New Zealand.

Elizabeth lives in Wellington with her husband, Fergus Barrowman, and their son, Jack.

Elizabeth Knox was kind enough to speak to The Fantasy Hive over email.

Your latest novel The Absolute Book came out in New Zealand last year and is out in the US and the UK this year. Would you be able to tell a bit about it?

I was looking for story in which to store—or reproduce—certain kinds of feelings. I’d had some very bad years where my mother had motor neurone disease, and my husband’s brother was killed, deliberately, leaving behind four children and a wife. Me and my husband Fergus were looking after people. We were sad and worn out. Once that responsibility eased off some I remember having this wonderful feeling of coming back to life. I wanted to write a book that did something with that feeling.

I wanted to capture the sense of freedom that comes with walking away at the end of a vigil. Of lifting your eyes, and seeing again how big the world is. A feeling of enchantment or maybe re-enchantment.

But I didn’t have a way in. And then I started thinking about the kind of books that I really like, bookish books, with scholarly heroes. Which is how I came up with Taryn Cornick.

Taryn is a woman who isn’t satisfied with the fact that her sister’s murderer was tried for manslaughter because of the unlikelihood of getting a conviction, because of the difficulty of proving intent—which is the story of the trial of the man who killed my brother-in-law. When we were at the trial on Rarotonga we drove inland to look at the outside of the island’s little prison—the shutters of its small windows propped open on squares of black air. You can’t look at the outside of a prison without feeling pity for everybody who ends up there. But when I invented Taryn I thought ‘what if this grief stricken young woman doesn’t have that moment of pity?’ So, Taryn seeks revenge.

My way into a book usually starts with a scene. That scene was of Taryn, the matron of honour at her friend’s wedding, who is unable to enter the church—someone whose actions in the past have opened her up to possession. But the demon inside Taryn doesn’t want to do what possessing demons normally do—generally be appalling—but wants to find out what Taryn knows by lurking inside her and slyly questioning people around her. Its questions are about an ancient scroll box known to have survived several historical library fires, the latest being one in Taryn’s grandfather’s library.

So that’s why the novel formed inside me, and how I found a way into the story.

The novel plays with the tropes of arcane thrillers, which in the acknowledgements at the end you say you find both fascinating and frustrating. What is it about the genre that made you want to play with it?

The novel plays with the tropes of arcane thrillers, which in the acknowledgements at the end you say you find both fascinating and frustrating. What is it about the genre that made you want to play with it?

It’s the scholarly heroes of the genre that I love. The protagonists whose heroic qualities aren’t martial or moral—they just understand things, can sort the evidence and see the big picture. But I was determined to write an arcane thriller that didn’t just hint at the magical and mystical. My preference is for the ones that go there, like Kate Mosse’s Labyrinth or Milorad Pavić’s The Dictionary of the Khazars.

The novel draws heavily on mythology, particularly the sidhe from Irish and Scottish mythology and the tylwyth teg from Welsh mythology. You really capture the uncanniness of them in the book. What drew you to them?

I’ve always liked stories about the tithe that Fairyland is said to pay to Hell. I wanted to explore the implications of that, to write about a beautiful society founded on theft. My decision was to have the stolen humans exchanged for the Sidh’s continued sovereignty, not for their immortality. The Sidhe stole territory from Hell, went to war with Hell, fought to a standstill, and made a treaty that requires them to periodically pay human souls to Hell. They have this enviable existence which requires them to treat others as instrumental.

The Absolute Book spans rural England, Auckland, fairyland and Purgatory. How do you go about capturing such vivid settings both real and unreal?

Here’s where I confess that I’m more or less describing what I see, because what I imagine plays itself out in in my head in the right light, with the best actors, the best setting. My imagination provides the set and cast and is the crew and director. I do as many takes as it takes, and even make the sun stand still in the sky, which lots of directors would love to be able to do. But it isn’t just transcription, of course. Even when you’ve got the dream of a scene running in your head, you never stop being the audience as well, a literate audience, who keeps going, “I see what you’re doing there”, so that you can tweak it as you go.

Which leads me to something that I’d like to say. I do like description in novels. The current school of thought is that it’s a virtue to strip novels of description. Or, the reader might want to know what the principal characters are wearing to a party, but not how the light looked on the water. My problem with this aesthetic imperative is that it’s anthropocentric. The world of this kind of novel is only going to be the people of the novel, their thoughts and actions, and never a flight of birds overhead, or the wind on the lake, or a flooded gutter, or a sleeping cat. It is as if it’s saying there is nothing in the world worth calling people’s attention to but people, the doings of people. I like the world to be there in my books. Allowing the non-human world into a book—particularly now when we urgently need to see it as just as central as ourselves—feels to me like a moral decision.

In January last year, The Absolute Book was the subject of a Slate article that went viral. What was that experience like? Why has the book struck such a strong chord with readers this past year?

In January last year, The Absolute Book was the subject of a Slate article that went viral. What was that experience like? Why has the book struck such a strong chord with readers this past year?

It was a blast. My New Zealand publisher would be getting a call from Disney while I was answering an email from Bad Robot. It was just nuts. One thing I loved is that my English editor actually got in touch with me about the novel the day before the madness started! So I get to feel there was some ordinary inevitability about the novel’s fortunes so far, as well as the miracle of Dan Kois’s Slate review. And I have to say it wasn’t just that Dan went to bat for the book—he also did a really winning job of describing the experience of reading it, and I think that made a huge difference.

Your novel The Vintner’s Luck (1998), about a peasant winemaker’s relationship with a fallen angel in Burgundy, won numerous awards. Would you be able to tell us a bit about it?

The Vintners Luck is a novel that proceeds year by year, chapter by chapter, following the life of a winemaker, Sobran Jodeau, from 18 to his death at 63. Sometimes a chapter will only cover the night of Sobran’s agreed on yearly meeting with the angel, Xas. Other chapters have more of Sobran’s year. And there are summaries of the whole years the two don’t meet, and of those few that they’re together the whole time.

Sobran is a peasant but has an enormous sense of entitlement. He is a self-loving man with a huge appetite for life and a powerful personality. He is sure the angel is for him. His guide, patron, friend, a gift he’s been given, a secret he hugs to himself. After twenty years Sobran discovers that Xas is a fallen angel, and the rest his story is him getting some chastened wisdom, a true sense of the world and his place in it, and what he owes his family, his neighbors, and the angel. Xas’s own story is strange, maddening to him – and we only get it very gradually. But his life has big implications for heaven and hell, just for a start. Sobran’s egotism and appetite for life are helpful when it comes to Xas because the man isn’t daunted by the size and scope of the angel’s existence. Running through the novel are all the great changes of the nineteenth century – playing off in the wings, as it were, because most of the novel is set in the Chalonnaise. And there’s a lot about wine—though it’s not a book about winemaking. It’s a love story.

You’ve also written the Dreamhunter Duet (2005-2007) and Mortal Fire (2013) for young adults. How do you find writing for a younger audience?

The adult and young adult books are both very much my own. I do dial back the language a bit for the YA – but I do so in the editing. Mostly I’m mindful of the fact I cannot do anything that deprives young readers of hope.

Your novel Wake (2013) is closer to horror than fantasy. The Absolute Book also features intense and frightening sequences. What draws you to these aspects of horror?

Your novel Wake (2013) is closer to horror than fantasy. The Absolute Book also features intense and frightening sequences. What draws you to these aspects of horror?

I want to move my readers – to make them laugh, cry, feel wonder. And I like sometimes to make them too frightened to turn out the light. I love reading horror – though I’m fussy about what I read. There are things horror can do better than other genres. It can do moments of crushing grief – I think here of the Spanish horror film The Orphanage. And it’s very good at the difficulty of looking after others – impossible to do, impossible not to try to do. Lots of horror has people trying to take care of others in the face of implacable forces – and the world does have its real implacable forces, like disease and natural disasters. In horror monsters often stand in for those things. Horror can deal with the big dark stuff of life by moving it into a story, concentrating and mitigating it.

Your novellas Paremata (1989), Pomare (1994) and Tawa (1998) are based on your experiences of growing up in Wellington. How does writing from your lived experience differ from writing fantasy?

My real experience makes it into the fantasy of course. But the autobiographical fiction and non-fiction are a totally different task. Firstly, they depend on memory – remembering, understanding my memories, shaping them as story – but not too much, only as much as they are story, which is probably less than they can be. I like to write anything autobiographical in small doses – so, essays – though I am writing a book about some crazy-making and difficult events in my life. It’s tough going, and I’ll admit I ran off with The Absolute Book to avoid it!

What’s next for Elizabeth Knox?

I’m finishing a YA novel. It’s science fiction and a school story. It’s called Kings Of This World.

Thank you Elizabeth Knox for speaking with us!