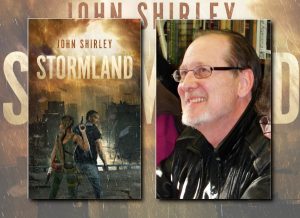

Interview with JOHN SHIRLEY (Stormland)

John Shirley is one of the original cyberpunk authors, and his Eclipse trilogy, comprised of Eclipse (1985), Eclipse Penumbra (1988) and Eclipse Corona (1990), is one of the genre’s foundational texts. His horror novels Dracula In Love (1979), Cellars (1982) and Wetbones (1991) were hugely influential on the splatterpunk genre. His short story collections Heatseaker (1989) and Really, Really, Really, Really Weird Stories (1999) have become cult classics, and the collection Black Butterflies: A Flock on the Dark Side (1998) won the Bram Stoker Award. A passionate musician, Shirley has fronted numerous punk bands, and has contributed lyrics to albums by Blue Oyster Cult. He is also well known for having written the original script for the cult goth film The Crow (1994), as well as writing scripts for various TV shows, including Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. His latest novel, Stormland (2020), is a cyberpunk climate change thriller set in a USA transfigured by extreme weather and heavy storms.

John Shirley was kind enough to talk with the Fantasy Hive over email about his latest novel and his incredible writing career.

Your new novel Stormland is out in April [April 13th 2021] from Blackstone Publishing. Would you be able to tell us a bit about it?

The novel is a futuristic detective tale, a fusion of cyberpunk and “climate-change fiction”, energized by a good deal of action and a perilous setting. “Stormland” is a colloquial term in the novel for a part of the SE USA where it’s constantly storming, bigtime, year after year, day after day, often very extreme hurricanes with only brief lulls between these major storms. The novel is set in what’s left of Charleston, SC, where only a small and highly stressed population remains, many of them people hiding in desperation in this highly dangerous place. Our main protagonist is a disenchanted former US Marshal who’s now a private detective hired to go to Stormland—and getting there is difficult in itself. Once there he finds it difficult to escape the place. He ends up partnered with a very strange man indeed and discovers that the series of murders taking place in the storm-wracked town have a bizarre, repellent origin…A great deal more goes on and we learn about the odd and interesting people in Stormland, the near-apocalyptic state of the USA in a perpetual climate-changed extreme-weather crisis and how it all connects to a predatory elite…

The novel explores a world transformed by climate change, in which the south-eastern coast of the USA is continually ravaged by extreme storms. Is science fiction uniquely equipped to help us imagine the future effects of climate change?

The novel explores a world transformed by climate change, in which the south-eastern coast of the USA is continually ravaged by extreme storms. Is science fiction uniquely equipped to help us imagine the future effects of climate change?

Science-fiction has always tackled possible big changes that could sweep the world—JG Ballard’s novel The Drowned World (1962) [review] seems prescient now, as one example of climate change fiction. Heavy Weather by Bruce Sterling (1994) is another example. Science-fiction writers often take on the challenges of imagining the Big Picture of the future: Transformations from robotics, from some technological “singularity”, from social despotism and druggy brainwashing as in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932). There’s Greg Bear’s Blood Music (1983). Big changes really can sweep over us globally now, because our mindless, inadvertent geo-engineering of the world is having overwhelming effects on the environment.

[Editor note: See our feature The Unseen Academic for more on Climate Change Fiction]

One of the novel’s characters is a former serial killer who has had his brain altered to cure him of being a psychopath. This is contrasted with the characters who have had implants surgically placed in their brains to control them. Where did these ideas come from?

Science. Neurologists and other scientists suspect that many serial killers are in some wise brain damaged, perhaps from birth. Lead poisoning in children has long been observed to cause violent behavior; other kinds of neurological damage, such as widespread exposure to the neurotoxins in pesticides, could be causing ADHD, and other developmental issues. Certainly, fetal alcohol syndrome can lead to criminally-inclined personalities. With all this to work from, scientists seek to develop ways to repair the brain—and because of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease they already have templates of experimental treatments in that direction. There are brain implants right now—certain implants use electrical stimulation to help resolve Parkinson’s symptoms, for example. Others are being experimented with. New bio tech is in the works all around us.

Your work is fiercely political – the Eclipse novels are about fighting against fascism, Everything Is Broken (2011), the Eclipse books and Stormland explore the link between privatization and corruption, the struggle for justice against classism and racism are recurring themes throughout your work. Do you feel art has a duty to reflect the struggles going on in the world around us?

I try to make any political statement inherent in the story, rather than some preachy fulmination of didactic heaviness. Yes, inherent in my A Song Called Youth trilogy (Eclipse, Eclipse Penumbra, Eclipse Corona), is a warning about disinformation used by white supremacy, but the tale is told as a science-fiction thriller. It’s not a lecture. Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) makes her point in the believable conditions of life faced by the women in the novel, and it’s a very compelling work dramatically. Stormland is carried out as more of a noir adventure…Art itself has no duty but to be art, to express the artist—that is, the artist’s “duty” is to try to be fresh, masterful, illuminating, something lasting…But for me personally, I feel a duty to dramatize injustice and to advocate a response to it, in an entertaining way. The best work of John Steinbeck was an inspiration for me. Also novels like John Brunner’s The Sheep Look Up (1972) develop theme through dramatizing the dilemmas of modern life…Stormland stages the catastrophic convergence of social injustice with environmental collapse. But it does it all in a futuristic noir thriller. I’m no luddite but my concern about the blind development of certain volatile technologies is also integral to the novel.

The A Song Called Youth trilogy, Eclipse: A Song Called Youth, Eclipse Penumbra and Eclipse Corona, is a cyberpunk classic and possibly your most well-known work. Would you be able to tell us a little about how it came into being?

The A Song Called Youth trilogy, Eclipse: A Song Called Youth, Eclipse Penumbra and Eclipse Corona, is a cyberpunk classic and possibly your most well-known work. Would you be able to tell us a little about how it came into being?

You ask how did the Eclipse books come about–I was asked to write a novel for a new line of books, and that big arc of story is what I had in me that wanted to come out. It was percolating in me. I had observed that in times of social chaos, demagoguery is a path to power for opportunists. We’ve seen it recently in our own country. The Big Lie takes root in the fear generated by chaotic conditions. Hence Nazism arose from the wrecked economy of Germany, post World War I. When I lived in France I saw how neo-fascism was recurring as the working-class French struggled to adapt to a wave of new immigrants from Africa and the Middle East. I could see the possibility of a new wave of racist fascism happening again, more prevalently, partly driven by the drive toward theocracy I observed in the USA, the new nationalism in the face of immigrants, and the likelihood of a breakdown of social mores in the wake of a future war…Lies, repeated enough—Qanon’s lies, now, is an example—take on a kind of viral life of their own. Falsehoods multiply in the hothouse wilderness that is the internet, and they mutate to dangerous new forms. I foresaw much of that in my Eclipse books, and the potential for a misuse of global media technology in the service of racist propaganda and disinformation. One thing I predicted that is quite worrisomely coming true now is “deep-fake videos”, as they are currently called. Videos that seem to depict real events in the “real world” that are actually just intricate CGI effects. These fake videos will be used to manipulate masses of people…The Eclipse novels are back in print through Dover Publications, I’m pleased to say.

You are one of the foundational cyberpunk writers. How do you feel about the genre now that we are living in an increasingly cyberpunk world?

The subgenre cyberpunk is still around in various forms—but much of what people think of as cyberpunk now is a mish-mash of manga/anime/cosplay tropes rather than what William Gibson and Bruce Sterling and Pat Cadigan and Rudy Rucker and Lew Shiner and I had in mind. Which is fine, let them enjoy it. It has its own special creativity…I haven’t read Neal Stephenson (I read mostly nonfiction and historical novels) but I take it he does some fine writing in a neo-cyberpunk arena. …It’s hard to keep up with technology enough to write predictively. I knew that 3-D printing was a coming thing, but was surprised to read the other day it has recently been used to print houses that are now going up for sale. Currently, just about the time I can imagine a technology it’s probably being manufactured somewhere! Cyberpunk for real is overtaking us. Still, “the street has its own uses” for technology…

Black Glass: The Lost Cyberpunk Novel (2008) originally started out as a planned collaboration between yourself and William Gibson. You collaborated with Gibson on short stories in the past. What led to the project falling apart and what made you come back to it?

Black Glass, which is still in print with a small press, was originally a screenplay. I wrote a draft, Gibson contributed some ideas and editing and we were going to go farther with it and then someone optioned it for a couple of years. That in effect put it on hold and it often happens that what’s optioned does not find its way into production. Thus, the realities of the that unreal place, Hollywood…Then Bill got very busy with writing demanding major novels. But the Black Glass story was there and I liked it and I asked him if I could develop it as a novel and he just gave it over to me to do with as I pleased. It’s also a noir thriller of the future, but rather more pulp, purposely so, than Stormland or Eclipse.

Dracula In Love and Cellars were a huge influence on the splatterpunk genre. How do you feel about that genre and your relation to it now?

Dracula In Love and Cellars were a huge influence on the splatterpunk genre. How do you feel about that genre and your relation to it now?

Oh, well, I don’t keep up on splatterpunk, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t good fiction of that kind being written or filmed. Both those books are still in print. Also my novel Wetbones influenced the genre, I think. I was just trying to bring a bit of hard-rock’n’roll vibe to the thing, bring some real creative wildness to it. I did grow up reading a good deal of horror, especially the elder writers like Machen and Lovecraft and Algernon Blackwood and Fritz Lieber and, a bit later, people like Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont and Shirley Jackson. I was influenced by certain works of Harlan Ellison, too. There are horrific elements in most of my science-fiction works, and in my dark crime fiction (as in the story collection Black Butterflies). I rather dislike “torture porn” films, like Saw, but I do like a good horror film. . .I have a lot of nostalgia and also rootedness in the elder horror and dark fantasy writers—I have a new fantasy novel from Hippocampus Press called A Sorcerer of Atlantis that is a sort of celebration of the Robert E. Howard, L Sprague De Camp, Fritz Lieber and Michael Moorcock Sword and Sorcery subgenre of fantasy. I do it my way—I always try to bring something original to any genre I work in—but it’s still a classic fusion of horror and fantasy and heroic adventure. It’s something I always wanted to do so I just went ahead and did it.

You are as famous for your short stories as for your novels. Do you approach the intensity of the short story differently from the long haul of the novel?

In the nature of things, one approaches short stories differently. But I try for a potent resonance going in a short story so we get a sense of almost a novel’s worth of character or situation or theme. A lot of my stories are idea-based and often the ideas could’ve generated whole novels. Once in a while they do: Stormland started out as a story for Interzone (and another part of it was in Analog Magazine). . .Novels, Stephen King said, are like marathon runs. A lot of writers run out of breath before they quite finish and come limping in. So I try to really keep the pace up and win the marathon, in a novel. A novel is more exploration of plot intricacies than short stories are, and of course they’re a much bigger canvas. Short stories are a more lapidary form. Novels too must have concision, and shouldn’t waste words, but short stories, ideally, are paragons of precision. I am drawn to them a lot, as evidenced by my having…let’s see…I think it’s nine story collections now. I am looking to re-edit and re-release my story collection Really Really Really Really Weird Stories late this year, and I have a brand new story collection of recent, previously uncollected stories coming shortly from Independent Legions: The Feverish Stars. I think it’s my best story collection since Black Butterflies—and that book won the Bram Stoker Award.

As well as novels and short stories, you have written for film and TV, most famously on the original script for The Crow. How does writing for TV and film differ from writing on the page?

Unless one is an “auteur” empowered by a megalomaniacal determination and, perhaps, excellent funding, one has to write scripts as a collaboration. Even if you have an original script—I have a number of original scripts right now I would like to get in front of people—once it’s picked up to be produced it’s filtered through producers, who plague the writer with notes. Sometimes they’re good notes, but sometimes they’re draining all the life out of it. Television writing is inevitably even more collaborative, as you have to filter it through producers, story editors, staff writers, and so on. Not that good things aren’t done that way, they often are. I like how my Deep Space Nine script came out under the aegis of Ira Behr, the showrunner. But still, you have to be a very social sort of personality to really thrive in that atmosphere. I’m not sure I’m that guy. When I’m on stage, I’m “social”—I snap into a special state of mind up there. But sitting across a table in a conference room, I’m uncomfortable… There is interest in Stormland in the film world. We’ll see. I doubt I get to write the script, if one is written…

Your passion for music shines through your work, and you have played in punk bands and written lyrics for Blue Oyster Cult. How do you feel your music influences your writing?

I played in several kinds of bands. Progressive funk bands—a bit like the Talking Heads I suppose—and simply hard-edged modern rock bands. But certainly punk is “root rock” for me…I’m influenced by progenitors like Iggy Pop, the Rolling Stones, Blue Oyster Cult, and Lou Reed…I hear music in prose—“You have to hear the music”, Harlan Ellison said—and I write, usually, while listening to music. I don’t find it distracting. I pick something that’s rather like the “soundtrack” for what I’m writing. It gives me energy, and helps keep me in the right state of mind. But of course I’ve been in rock bands or associated with them, for most of my adult life. I’m the lead singer and lyricist for my band The Screaming Geezers (https://www.screaminggeezers.com ) and we recently released an album and opened for the Blue Oyster Cult in a big venue in Portland. Which went great. But then the pandemic hit and that’s on hold. I also work in a different style of rock, more progressive, with guitar master Jerry King, eg on our album Spaceship Landing in a Cemetery. I’m pretty excited about the new Blue Oyster Cult lp, The Symbol Remains—their first studio album in nineteen years—as it’s one of the top-twenty albums for sales on Billboard. I wrote the lyrics for five of the songs on The Symbol Remains including the two singles, That Was Me and Box in my Head. The videos for those singles are having major success on youtube. So that’s all very thrilling for me. Now if this pandemic would just end. I’ve just gotten my covid vaccine, and hope to be back in rehearsal in a couple months…

What’s next for John Shirley?

If Stormland does well when it’s released—so far it’s got a great review from Publisher’s Weekly, and some wonderful blurbs—I hope to write a sequel to it. It stands alone, but I had hopes of it becoming the first book of a trilogy. I also have a novel called Axle Bust Creek coming later this year. I’m developing a new album with Jerry King—we’ve gotten good reviews in Prog Magazine for earlier material—and I am planning to submit stories to Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine and Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. I am haunted by visions of dark crime…

Thank you John Shirley for speaking with us!