Interview with Tim Powers (FORCED PERSPECTIVES)

Photo: Matt Gush

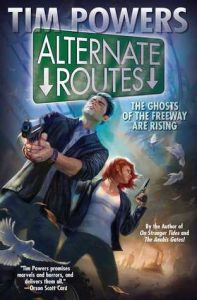

Tim Powers is a unique voice in Fantasy. He specialises in rigorously researched secret histories, in which gaps in the historical record are explained by the fantastical or the supernatural. But this description hardly does justice to his incredible novels, which are among the most inventive and joyous I have ever read. His Philip K. Dick Award winning novel The Anubis Gates (1983) is a delirious time travel tale involving body-hopping werewolves and Egyptian mythology. The Drawing Of The Dark (1979) imagines the Siege of Vienna as a magical battleground involving the reincarnated King Arthur, and The Stress Of Her Regard (1989) imagines Keats, Byron and Shelley fighting lamia. Powers has won the World Fantasy Award twice, once for Declare (2001), which combines spy thriller with Lovecraftian horror, and once for Last Call (1992), the first of the Fault Lines trilogy, which imagines Bugsy Seigel as the Fisher King. Along with K. W. Jeter and James Blaylock, he is a pioneer of steampunk. His latest novels, Alternate Routes (2018) and Forced Perspectives (2020), see Powers bring his strange magic to modern day Los Angeles.

Tim Powers was kind enough to speak to The Fantasy Hive via Zoom.

You had two books come out last year, Forced Perspectives, which was the sequel to Alternate Routes, and also The Properties of Rooftop Air with Subterranean Press, which is in the same world as The Anubis Gates. Would you be able to tell us a little bit about both of them?

You had two books come out last year, Forced Perspectives, which was the sequel to Alternate Routes, and also The Properties of Rooftop Air with Subterranean Press, which is in the same world as The Anubis Gates. Would you be able to tell us a little bit about both of them?

Well, start with the latter. Bill Schaefer at Subterranean Press has twice asked me if I would write a short story set in the world of my 1983 novel The Anubis Gates. And I figured, certainly there are a lot of peripheral characters in that novel who it would be interesting to look at more single mindedly. Sort of the way Jack Vance wrote individual stories set in his world of the Dying Earth. And so in one of these stories for Schaefer at Subterranean called Nobody’s Home, I had a sort of little mini adventure of a character named Jacky Snapp from The Anubis Gates. And in Properties of Rooftop Air, I amplified on a very minor character, whose name I don’t think I remember. But in each case, it was, as I say, a short story in that universe, involving some otherwise fairly peripheral characters. I thought it would be kind of fun to do, like ten of them, and have a book of short story supplements to The Anubis Gates.

How did you find returning to those characters after all that time?

Actually, it was pretty easy to fit mentally back into the Anubis Gates world again. That sort of Regency London. Luckily, there’s a number of research books written by a guy, a sort of historian sociologist, Henry Mayhew, who extensively researched low life in London in the 19th century. Legitimate people like bankers and fishermen and merchants and also thieves and forgers and prostitutes. Henry Mayhew was kind of an upper class, a gentleman who was obsessed with studying the lower orders. With his books, there’s simply no limit to the research available. A hundred writers could write one hundred books, using Mayhew, and really not ever overlap one another.

Oh, and then you mentioned Forced Perspectives. That is a sequel to a previous book called Alternate Routes. And both books and one that is coming out next spring, which is a third in the series, take place in modern Los Angeles and involve a couple of characters, a man and a woman, who have the Secret Service background, though they’re kind of fugitives these days. And they keep running into the supernatural perils that threaten the world. Los Angeles, luckily, is almost like London on an admittedly much smaller scale. It’s a real gold mine of odd developments, weird history, strange fugitive cults… you don’t run out of interesting stuff!

You’ve written a lot of other books set in California, including the Fault Lines trilogy and Three Days To Never. So I’m guessing you find it a very fruitful place to write about.

Yeah. For one thing, I live in Southern California, so it’s easy to go physically look at places. Somebody said, at some time, the country was tilted, so everything loose fell down to the west coast. And as I say, it’s got deserts with weird hermits and strange secret societies out living in trackless wastes, and it’s also got dense urban areas, which are so dense that the weirdest sort of businesses, organizations, strange sub-cults can exist unnoticed. And for me, the fact of the freeways has always been intriguing. There’s something about these five fast roads that get you anywhere in implausibly short times that invites a mystical interpretation. The common term for ordinary streets is surface streets. So I think, okay, if ordinary streets are surface streets, then freeways must be deep streets, obviously. So yeah, I’ve always thought that there is a natural connection with freeways and supernatural complications. It’s been fun to extrapolate on that. Also, there’s an advantage in using here and now stuff – freeways, big lighters, cell phones, 711 Mini marts – as an aid to tricking the reader into believing for the duration of a story that these events are really happening to real people in real time. It’s not an alternate world, it’s this world.

The idea of the secret history, that there’s this supernatural world happening underneath the recorded world that we know, is a big thread running through all your work. What first drew you to this idea?

The idea of the secret history, that there’s this supernatural world happening underneath the recorded world that we know, is a big thread running through all your work. What first drew you to this idea?

I think of books like Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 or V, where they’re very aggressively set in this real world, the same world the reader is living in. I’ve found it useful a lot of times to look at a real historical situation involving the siege of Vienna or the spy Kim Philby, or Blackbeard the pirate or Thomas Edison, and read their biographies, books about them with a kind of paranoid squint. Looking for behaviour that makes no ostensible sense. You think, why would Edison or Blackbeard or Bugsy Siegel in Las Vegas have done this? It’s completely irrational! And of course, any person does do a lot of irrational things during their life.

But for the purposes of fiction, I tell myself, what if that was not irrational? What if that apparently crazy behaviour was actually very shrewd, if you know the whole story? And the whole story, of course, involves the supernatural? And so given that basis it’s really very easy to find a lot of strange behaviour, and then you say, in what supernatural context was this behaviour sensible? There’s always something to find. It’s sort of like being a cold case detective, looking at evidence and saying, okay, what was actually going on? And so I come up with, well, it was vampires. Well, it was ghosts, Bugsy Siegel was the Fisher king. Of course, if I believed any of these explanations, I’d be crazy. But I do work to make them as perfectly plausible as I can. So that the reader would think, well, obviously, this isn’t true. But where did Powers fictionalize? And if they look into it, they’ll say, well, this is true, he really did do that. He really did meet so and so. And I want the reader to think maybe, maybe it’s true, at least for the duration of the story.

How much historical research goes into getting all the surrounding details just right?

I try to get it as accurate as possible. I mean, I don’t want it to be possible for a reader to say, Hmm, I wonder if that’s true. To look it up and say, Oh, well, no, Einstein wasn’t there. Einstein was in Germany at that point. I want it to stand up to a fairly rigorous checking. As opposed for example, to Dan Brown’s book, The Da Vinci Code, which, you read it, you think, wow, this is fascinating. All this secret knowledge. Let me check it out. And two minutes with the Britannica contradicts it. I want my fictional backstory’s secret supernatural world to stand up to more checking than that. I want it to be uncontradictable. People can say well, now, firstly, Shelley was not born the secret twin of a vampire. And I say okay, well prove me wrong. Find something in the historical record that contradicts my explanation. Admittedly, my explanation is nonsense. But, If I’ve done my work correctly, you can’t find anything in the historical record that rules out my explanation.

Speaking of Percy Shelley, and the other Romantic poets, they seem to be another recurring element throughout your stories. The Stress Of Her Regard deals most overtly with the Romantics, but Lord Byron shows up again in The Anubis Gates. What keeps drawing you back to them?

Speaking of Percy Shelley, and the other Romantic poets, they seem to be another recurring element throughout your stories. The Stress Of Her Regard deals most overtly with the Romantics, but Lord Byron shows up again in The Anubis Gates. What keeps drawing you back to them?

Good question. I just find something, especially in the case of Lord Byron, absolutely fascinating about them. People often use the term larger than life, but Byron really was. I remember when his doctor Polidori, who had poetical ambitions himself, one time asked Byron, “Well, what is it my Lord that you can do that I can’t?” Byron thought for a second and then said, “Well, I think there’s three things. I can swim the Hellespont. I can put out a candle with a pistol ball at thirty paces. And I can write a poem that sells 30,000 copies in a day.”

There was just something so bravura about Byron’s life – handsomest man in Europe, but lame, with a clubfoot. This horrible marriage. He had a child by his half-sister, fled in disgrace to Switzerland and Italy, and never went back to England. He didn’t participate in any duels but challenged people to several. And then of course, died in Greece at the age of 36, fighting for Greek independence from Turkey.

You just think that is the stuff of romance more than a plain literal biography. And then his poetry, the later cantos of Child Harold and Don Juan lives up to his life. It also is extravagant and full of bravura. Keats and Shelley kind of pick up glamour from their associations, especially Shelley with Byron. Poor Keats had kind of a shabby and short and tragic life, which lends itself to the full Romantic style. And Shelley was kind of a bastard really. But drowned at age 30, going off sailing on a day when everybody told him there was a big storm coming, and he didn’t even know how to swim. Shelley and Byron certainly had active interest in supernatural stuff. So they just sort of were begging for this kind of fictional handling it seemed to me.

And with Hide Me Among The Graves (2012) which comes later, you have that link through Polidori which, once you have The Stress Of Her Regard in place, presumably that just naturally links you through to the Rossettis as well?

I didn’t intend to write a sequel to The Stress of Regard. But I was idly reading a biography of Christina Rossetti just through fun, and I discovered that John Polidori, who had been a pretty significant character in The Stress Of Her Regard, was her maternal uncle. Then I discovered that she had a lot of dealings with Edward John Trelawny, who also had been a character in The Stress Of Her Regard.

Then I discovered that her brother Dante Gabriel Rosetti, when his wife killed herself, he was feeling guilty about it, so he took his notebook of all his poetry and laid it in her coffin, at the funeral, and his poetry was buried with her. And then a couple of years later, a publisher told him if you had a collection of poetry, we could publish it. He said, Give me a couple of days. And he dug her up and retrieved the book. And it instantly seemed obvious to me that retrieving the poetry was the excuse for digging her up. I mean, it’s obvious. Obviously, he needed to put something else in or take something else out. And so given Dante Gabriel Rosetti’s adventures with his wife’s grave, and the fact of Polidori and Trelawny being involved in the picture, a sequel to The Stress Of Her Regard was inevitable.

It was fun to take the kind of paranoid squint that I had used to look at Byron and Keats and Shelley, and use it on the pre-Raphaelite crowd. Swinburne and the Rossettis in the setting of Victorian, rather than Regency London. So there was the Victorian embankment now instead of the river edge being where it had been, and so it was fun to deal with a slightly more modern London.

As well as writing about poets, you have your own fictional poet, William Ashbless, from The Anubis Gates. You and James Blaylock have written poetry as Ashbless. How did that come about?

Well, that goes all the way back to 1972. Blaylock and I were in college, and the college paper published poetry. 1972 was close enough to 1968 that the poetry was all nonsense about rainbows and children playing naked on the beach and things like that. We decided that we could write poetry that would sound very pretentous, but be, in fact, nonsense.

And so one of us would write a line on a piece of paper and pass it to the other, who would write a following line and pass it back. We would pass the paper back and forth, until we had got to the bottom of the page and then we’d bring it to an ending. We sent five or six of these to the school paper, and they published them. But we needed a name for our poet. And I said, it should be one of those two word names like Longfellow, or Wordsworth. And so one of us came up with the syllable “ash” and the other came up with the syllable “bless”. Ashbless seems better than Blessash. So we said some more poetry and they published that too, and Ashbless kind of got to be a thing we played with.

So when I sold The Anubis Gates to Ace books, and I needed the name for a kind of crazy poet, I of course used William Ashbless. Blaylock meanwhile, had written a book called The Digging Leviathan, in which he also needed the name for a crazy poet. And of course he used William Ashbless. And he sent that to Ace books, and the editor wrote to him and said, Do you know Powers? Do you know each other? Why do you both talk about this William Ashbless? And why does Powers have Ashbless in 1810, and you have Ashbless in 1960? And Blaylock said, I’m sorry, I didn’t realise that Powers used the name too, I’ll use a different one. And the editor said no, no, no, make it the same character. Figure out why he is still alive in 1960.

And so ever since Blaylock and I have used that name. We wrote a cookbook, the William Ashbless Memorial Cookbook which Subterranean Press published. Ostensibly, we were writing it because Ashbless had disappeared and apparently died. And in his memory, we had gathered these favourite recipes of his. And in an afterword Ashbless explains that he’s not dead, and he denounces us for having kept the royalties for the book! So I’ve come to think of it as kind of a good luck gesture to mention Ashbless in every one of my books. I don’t want readers to say, oh, look, Powers is mentioning Ashbless again, it’s like Alfred Hitchcock always having a cameo in his own movies. So I’ve, I’ve translated it. It’ll be Guillermo Cenere Bendiga, maybe Wilheim Asche Segne. So ideally, readers won’t notice. But for my own reassurance, I can tell myself, yes, you did put the name in there. Your little good luck charm is included. In fact, when The Anubis Gates was first published, in that book, I say that Ashbless was a minor 19th century British poet. That was in the days before the internet. So a lot of people assumed that he actually had been a real existing poet. They’d never heard of him because he was a very minor poet. But a lot of people did go to libraries and try to look him up, which was fun. In fact, I think even now, William Ashbless, has a bigger Wikipedia page than either Blaylock or I do!

Speaking of Blaylock. I was going to ask you about the label steampunk, which I think it was K. W. Jeter who came up with it as a sort of joking way to talk about the books that the three of you were writing at the time, and it’s sort of taken on its own weird life of its own since then?

Speaking of Blaylock. I was going to ask you about the label steampunk, which I think it was K. W. Jeter who came up with it as a sort of joking way to talk about the books that the three of you were writing at the time, and it’s sort of taken on its own weird life of its own since then?

Right. Jeter has wished sometimes that he had trademarked that term, steampunk! But yeah, in fact, it goes back to Henry Mayhew. It was Jeter who discovered Henry Mayhew’s books and told Blaylock and I about them. As I say, those books are such rich, gold mine material that Blaylock and I both wrote books set in 19th century England. And so, in the space of only a few years, Jeter published, Morlock Night, a sort of sequel to HG Wells’ The Time Machine. And I published The Anubis Gates, which took place in London in 1810. And Blaylock published Homunculus which took place in Victorian England. All three were science fiction or fantasy, because that’s the stuff we write. If it had been young mystery writers who had found Mayhew it would have probably resulted in some neo-Sherlock Holmes type work.

Jeter wrote a letter to Locus Magazine in ’87. Saying, we’ve already had cyberpunk. There should be a word for the stuff me and Blaylock and Powers are writing. How about steampunk? And it turned out to be a tremendously attractive idea. Of course, we didn’t invent it. There were a lot of books and stories before us that anybody could recognize as steampunk. You know, science fiction and fantasy set in Victorian London. But because Jeter coined the word and pointed to himself, and Blaylock and I, we’ve been sort of unjustly identified as the inventors of it. And it’s fascinating the way it has progressed. Cherie Priest with Boneshaker, any number of movies now.

The concept of steampunk seems to have moved from books to costume. At a lot of conventions you see people with outlandish mechanical rifles and goggles and artificial arms and always with that Victorian style machinery. Very pretty brass and the kind of superfluous decoration that they used to put on gears and levers. It’s fascinating stuff. I love all the costumes, auxiliary stuff, all the little extra lenses on the glasses. It’s been fun to watch it as it has certainly moved away from anything I had in The Anubis Gates. I think probably the most perfect steampunk novels, in the sense of Victorian era science, with kind of a crazy Gonzo tilt, but still with plausibly Victorian sensibility, are Blaylock’s Homunculus, and Lord Kelvin’s Machine. It’s been a fascinating development. God knows what a sociologist would make of it.

Another element that’s popped up multiple times in your writing is King Arthur – the reincarnation of Arthur turns up in Drawing Of The Dark, but also you have the thing with the Fisher King in Last Call. I think I read somewhere that the three of you had a plan with Jeter to both do a King Arthur Returns book, but at different points in history?

Yeah, that was a deal that the Laser Books editor Roger Elwood came up with in about 1976. He said, there’s a British publisher who would like to have ten novels involving King Arthur reincarnated throughout history. So you’d have King Arthur chopping open Nazi tanks with Excalibur, for example, or sinking the Spanish Armada. And Jeter and I agreed to participate. We were very young. We got together with Ray Nelson, a science fiction writer, and we divvied up history. I got the siege of Vienna in 1529, Jeter got Victorian London. I think I had highwayman in the 18th century. And so we all began writing books about King Arthur reincarnated. And luckily, the project fell through. The British publisher decided they didn’t want it after all. Because I think if they had, I think the ten books would have been published under a house name. And they had a strict 60,000 word limit.

When it fell through, the three of us looked at each other and realized, very shortly, publishers are going to be flooded with our books about reincarnated King Arthur – I’m going to get mine printed before you get yours printed! And so Jeter did manage fairly quickly to sell Morlock Night. My contribution, Drawing Of The Dark, in which King Arthur was reincarnated to repel the Turks at the siege of Vienna in 1529, was rejected a number of places, but then very fortunately, landed with Lester Del Rey at Balentine Books. He said, Okay, I might buy this, if you double the length, get rid of this year gap in the chronology, don’t have the hero die at the end, and a number of other things. I thought, well, nobody else is buying anything of mine. Okay. And so I rewrote it. And I would say I improved it, but it’s more accurate to say I made it a whole different book and Del Rey published it.

It involved the Fisher King, which is a fascinating figure in mythology. As far as the British Isles go, it seems to show up earliest in Welsh mythology [Editor note: Peredur from Y Mabinogi]. Then there’s people like Chrétien de Troyes, who wrote Percival about the Fisher King, and I believe Percival is incomplete. De Troyes died before he finished writing it. But the Fisher King is a fascinating character in mythology, because he’s unexplained, it’s mysterious. A knight visits him and sees a chalice and a lance, which have to do with Christ, of course. And if he asks about the chalice all will be well, but if he asks about the lance, things are gonna go badly. The Fisher King himself is injured in some way that makes him sterile or impotent. Sometimes he’s injured in the groin, sometimes he’s partially paralyzed. His incapacity is reflected in sterility of the land, or else the sterility of the land causes his incapacity, there’s a link there either way. And it’s never explained. Reading the Fisher King myth, you keep thinking, where’s the missing chapter that explains this?

He’s a figure that shows up in other mythologies. In the oldest of the Arabian 1001 Nights. There are fish, that for one thing they’ll stand up and sing if you put them in a frying pan. But they’re from a lake that used to exist in the desert when this one area of the Arabian Desert was green and verdant, but it has now become sterile and desert. And there’s a king in a ruined castle. They’re in the middle of this Ozymandias desolation. And he’s sitting in a doorway, and he is stone from the waist down, which obviously effectively makes him impotent and sterile. And I thought, okay, that’s the Fisher King. I’m not making this up. That’s recognizably an Arabian Fisher King. I doubt that the original writer of that Arabian story, had talked to a pilgrim from Wales, and heard the story.

He’s a figure that shows up in other mythologies. In the oldest of the Arabian 1001 Nights. There are fish, that for one thing they’ll stand up and sing if you put them in a frying pan. But they’re from a lake that used to exist in the desert when this one area of the Arabian Desert was green and verdant, but it has now become sterile and desert. And there’s a king in a ruined castle. They’re in the middle of this Ozymandias desolation. And he’s sitting in a doorway, and he is stone from the waist down, which obviously effectively makes him impotent and sterile. And I thought, okay, that’s the Fisher King. I’m not making this up. That’s recognizably an Arabian Fisher King. I doubt that the original writer of that Arabian story, had talked to a pilgrim from Wales, and heard the story.

It seems to me that that story must be, or at least ought to be, part of the Jungian subconscious. That story must be hardwired at the very bottom of everybody’s mind. And therefore, if you use that figure in fiction, that bottom wiring of everybody’s mind will recognize it was subconsciously will say, Oh, yeah, that guy, right. And so it was a lot of fun to translate it to Las Vegas in the 1940s. Because Bugsy Siegel decided to build a palatial casino at the insane cost, at a sort of little desert crossroads, a little place where you would get a hamburger and fill your gas tank on the way from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles. It was just a crossroads. But they had gambling. And so Siegel built the Flamingo hotel, which was insanely grand. And – this struck me – he opened it on Christmas Eve, closed it on just about exactly Good Friday, and re-opened it on just about exactly Easter. And I thought, Okay, I get it. And then Siegel himself died because he left his castle and went to Los Angeles. On I think it was August 20. But it was the day in Babylonian mythology, when the god Tammuz is ritually killed. And Seigel was murdered. Somebody shot him, in fact, shot his eye out. And I thought well, okay, I’m not making this up. This is all true. And so it was a very short step to say that Siegel was the Fisher King phenomenon happening in the American West. In fact, I probably started to stumble on it because I was reading T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland. And of course, there’s a bit in there where it says, I will show you something different from your shadow at morning. behind you and your shadow at evening rising to greet you. And that’s obviously somebody walking east, and he talks about the perilous chapel in the wasteland. Okay, if you’re going east from Los Angeles, looking for a perilous chapel in a wasteland, obviously, it’s Las Vegas. And Elliot also talked about tarot cards in the wasteland. And if you think about cards in Las Vegas, well – playing cards. And playing cards I discovered are descended from the Tarot deck. And so really, I was connecting dots that were already prominently there. Sometimes late at night, I would wonder, you know, Powers maybe you’re not making this up. Maybe you’ve stumbled on the real story here! In the morning, I would be okay again.

And to to bring us to a close some What are you working on at the moment?

Oh, at the moment, I just sent a novel into the publisher Baen Books. And, as usual, the editor wrote back and said, this is good, but here are some things you need to fix up. That always happens to me. And after a day of sulking, I look at the advice and think, well, yeah, those are improvements. I better do it. I just recently finished rewriting it and send it off. I’m kind of waiting to hear him say yes, now it’s good.

In the meantime, I’m doing a 20,000 word novella for Bill Shaffer and Subterranean Press. And vaguely thinking about what the next novel will be. It might be a fourth in the series that included Alternate Routes and Forced Perspectives. And this new one, which I think will be called Stolen Skies. Or it might be something else entirely. I’m kind of just idly making notes and looking around and scratching my head.

Thank you, Tim Powers, for speaking with us!