SISTERSONG by Lucy Holland (BOOK REVIEW)

“I wander so long, it feels as though I’ve crossed some hidden boundary. I’ve left our world for theirs – the nameless land where goddesses sing to the stars, where lost spirits linger in the twilight.”

Lucy Holland’s Sistersong (2021) is a fantasy novel based on the Child Ballad ‘The Twa Sisters’. The Child Ballads represent a strain of ancient British folklore rife with fairies, magic and blood that has served as an inspiration for some of Fantasy’s finest novels, from Diana Wynne Jones’ Fire & Hemlock (1984) to Ellen Kushner’s Thomas The Rhymer (1990). As such my expectations for Sistersong going in were particularly high. I am delighted to say that Holland’s novel more than lived up to my expectations. Holland beautifully captures the dark, sinister feel of the original ballad, whilst crafting a powerful story full of compelling characters. Mixing elements of historical fiction and Fantasy, Sistersong tells a story set in ancient Devon, of the Britons and their traditional pagan beliefs coming under threat of the Saxons and Christianity. The novel powerfully imagines the lives of women and trans people in this setting, stories erased by a history recorded by generations of patriarchal straight white men. Beautifully written and with a keen eye for historical detail, Sistersong demonstrates the power of these old familiar ballads when they are opened up to new perspectives.

The novel tells the story of the three children of King Cador of Dumnonia. Riva is a healer who bears the scars of a childhood injury which left her hand and leg burned. Keyne has inherited the King’s magical bond with the land, and knows himself to be a man despite a society that sees him as a woman. And Sinne is a seer just coming into her abilities, who dreams of love and adventure beyond the confines of their community. All three siblings live in a precarious time – Gildas the priest has disrupted the King’s sacred bond with the land with his new Christian beliefs, just as the Saxons threaten to invade. But this is nothing compared to the disruption brought by the handsome and mysterious stranger Tristan, who steals Riva’s heart, driving a wedge between the three siblings that leads to more far-reaching and tragic consequences than any of them could have anticipated.

The novel tells the story of the three children of King Cador of Dumnonia. Riva is a healer who bears the scars of a childhood injury which left her hand and leg burned. Keyne has inherited the King’s magical bond with the land, and knows himself to be a man despite a society that sees him as a woman. And Sinne is a seer just coming into her abilities, who dreams of love and adventure beyond the confines of their community. All three siblings live in a precarious time – Gildas the priest has disrupted the King’s sacred bond with the land with his new Christian beliefs, just as the Saxons threaten to invade. But this is nothing compared to the disruption brought by the handsome and mysterious stranger Tristan, who steals Riva’s heart, driving a wedge between the three siblings that leads to more far-reaching and tragic consequences than any of them could have anticipated.

Anyone who knows the original ballad knows the grisly fate awaiting one of the sisters. Holland manages to capture the tragedy, horror and sheer strangeness of the original ballad, whilst fleshing out the characters in her own way. The fact that we come to know Riva, Keyne and Sinne as people makes the tragedy and the horror all the more powerful. Similarly the historical context of the Britons and the Saxons, the old beliefs in magic and the old gods being swept away by the rising tide of Christianity, anchors the book in the real whilst accentuating the folk tale and fantastical elements into an epic conflict. Holland’s well drawn characters and well researched historical details make the story feel vivid and lived in, even as the magical and fantastical elements grow in prominence. The climactic scene where we first see the harp – again if you know the ballad, you know – is appropriately horrifying. Yet for all its tragedy, Sistersong is not a depressing book, and Holland manages to find surprising triumphs for even her most doomed characters.

The novel is split between the three perspectives of the siblings, all of whom are well drawn and compelling. Holland manages to make Riva, Keyne and Sinne sympathetic and understandable, so that even when their choices and decisions lead them to their inevitable tragedy, we feel for them. The jealousy that grows between Riva and Sinne is all the more tragic because they do genuinely care for each other, making their ultimate fates all the more distressing. Riva is introverted and traumatised by her injuries, and harbours resentment for Sinne’s easy-going charisma and beauty, whereas Sinne finds herself resenting Riva for having the adventure and romance Sinne always dreamed of fall into her lap. Keyne struggles to live in a world that is intent on seeing him as female, until the genderfluid druid Myrdhin, who also lives as the witch Mori, shows him how he can claim his gender identity. The three siblings are all brought up within the confines of a society that sees a very limited future for them as girls and women – they are to be married off to seal alliances between other kingdoms to keep Dumnonia safe, and produce heirs. All three of them wind up rebelling against the strict societal expectations placed on them, made stricter by Gildas and the patriarchal nature of the Christian church. It is the struggle against these restrictions that Sistersong is about at its heart. Holland’s novel is an exploration of what life might be for women and trans people in these societies, an exploration of how they might gain agency in such a society, and a railing against those such as Gildas who would close down their options. It is also a reflection on the nature of recorded history – Gildas is a real figure in history who is one of the few recorded sources for the time and place that Holland is writing about, a man with obvious priorities and axes to grind that would shape the history he records. Similarly, the ballad itself, with its story of violence between two sisters for the sake of a man, and the mysterious third child who appears at the beginning of some versions then entirely disappears, is in its own way another form of history that serves a particular voice, viewpoint and agenda. Holland’s novel is a bold and compelling attempt to give those silenced voices a chance to tell their stories.

In Sistersong, Holland draws from a particularly rich vein of British folklore and adds her own distinct voice and philosophy, one that allows us to appreciate all the dark magic of the original whilst asking important questions about the nature of the histories we are left with. It is a wonderful work of modern Fantasy and I look forward to whatever Holland does next.

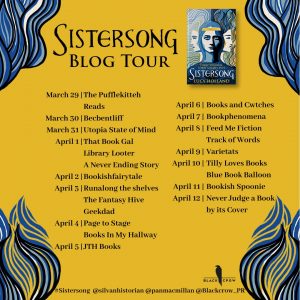

Be sure to check out the other stops on the Sistersong blog tour!

[…] religion whose values are at odds with those of the majority of Brittons. What I didn’t know (and learned from fellow contributor Jonathan Thornton’s review) is that elements of Sistersong are also based on a ballad, “The Twa Sisters”. That Holland […]