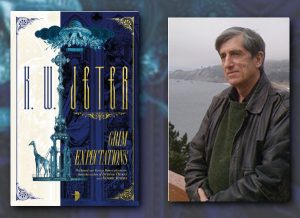

Interview with K. W. Jeter (GRIM EXPECTATIONS)

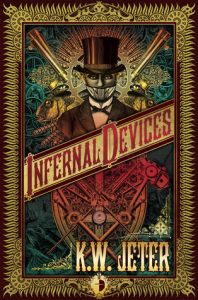

K.W. Jeter is one of genre fiction’s pioneers, whose work crosses the boundaries of SF, Fantasy and horror. He coined the term ‘steampunk’ in 1987 to describe the novel he, Tim Powers and James P. Blaylock were writing, and his novels Morlock Night (1979), a sequel to H. G. Wells’ classic The Time Machine (1895), and Infernal Devices (1987) are early classics of the genre. He also wrote Dr Adder, written in 1972 but unpublished until 1984, which with its fascination with body modification and body technology and its use of transgressive sex and violence can be read as a precursor to the cyberpunk genre. Among his other novels are Farewell Horizontal (1989), a deeply original post-apocalyptic story that occurs on the side of a huge building, Madlands (1991), in which dreams of Los Angeles overwrite reality, and the dystopian post-cyberpunk Noir (1998). More recently, he has written two follow ups to his classic Infernal Devices, Fiendish Schemes (2013) and Grim Expectations (2017), the latter published by Angry Robot, who also reissued Morlock Night and Infernal Devices for a new generation of readers.

K.W. Jeter was kind enough to speak to The Fantasy Hive via email.

You recently returned to your George Dower books with Grim Expectations, the follow up to Infernal Devices and Fiendish Schemes. What was it like returning to the world and the characters so long after the first novel in the sequence?

You recently returned to your George Dower books with Grim Expectations, the follow up to Infernal Devices and Fiendish Schemes. What was it like returning to the world and the characters so long after the first novel in the sequence?

I had changed in the meantime, and so had the characters, particularly in regard to my perception of the world in which they found themselves. Infernal Devices was essentially a comic novel, or at least so I’d thought at the time of writing, and for quite some time afterward. My return to that world & the writing of the subsequent books in the trilogy was largely prompted by a growing awareness that there was more there than mere fun & games, and watching a hapless protagonist flail about in a world, the complications of which seemed designed to thwart his mere desire to lead a comfortable life; as with all the best humorous novels, there seemed to be something more serious going on underneath. Steam power becomes a metaphor for technological advances in general, and the dire effects they have on the world, as others besides myself suspect we are beginning to see with information technology. Not that it did them any good, but the Luddites were prescient in this regard; their world was indeed shattered, as ours might well be. The Luddites’ only error was in thinking that they could do anything about it.

You coined the term ‘steampunk’ to describe the work you, Tim Powers and James Blaylock were doing. How do you feel about the genre now?

What Jim & I were doing was a bit of a lark at the beginning, without much more intent other than entertainment, at which I think we both succeeded rather well. It’s somewhat astonishing to me that the whole thing became a genre in itself, in which both he & I could do some work a little more serious in nature. A lot of this is not due just to our own efforts, but to the talents of other writers who picked up the ball & ran with it, so to speak. There’s a certain crowd I think of as the “anti-colonial” steampunk writers, who’ve done some interesting work, using steampunk’s fractured historical approach as a critique of not just British history, but of the entirety of world history. The potential of the genre has only been slightly tapped; there’s a lot more to come.

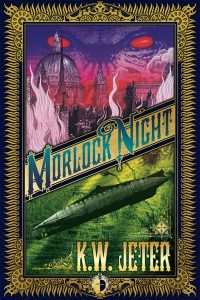

You wrote Morlock Night, a sequel to H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine. What drew you to Wells’ work, and how did you approach such an iconic piece of SF history?

You wrote Morlock Night, a sequel to H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine. What drew you to Wells’ work, and how did you approach such an iconic piece of SF history?

As a science fiction writer, to not be drawn to Wells’ work would be like living in Tibet & not being aware of the Himalayas. More so than Verne or any other writer, Wells is where it all starts; he didn’t give birth to the twentieth century, but he gave birth to the observation of the twentieth century & the modern age. To fool around with any part of his work requires a certain irreverent attitude, but also the setting aside of the realization that you’re not really going to come up to more than his shins. All you can do is take what you can from Wells, then write & fill in the rest as best you can.

Your novel Dr Adder was written in 1972 but wasn’t published until 1984. It is now seen as a pioneering work of cyberpunk fiction. Would you be able to tell us a bit about its journey to publication?

I don’t consider my novel Dr Adder to have anything to do with cyberpunk; I wasn’t influenced by it, and I don’t see where I’ve had any influence on it. The difficulty I had in getting Dr Adder published was largely due to my having no reputation or track record as a writer; it was literally the first thing I ever wrote. Publishing is a business, and as such is hesitant to take risks, and that’s just the nature of business enterprises in general. If I’d made a bit of a mark by getting some short stories published first, it might not have taken so long for the book to see print. At the same time, it was kind of a weird experience getting rave-up fan letters from editors to whom I’d submitted the manuscript – “This is exactly the kind of book we should be publishing!;” that’s a direct quote – who’d then conclude their letters by saying they weren’t going to publish it.

Dr Adder deals with ideas around body modification and body technology that make it feel very prescient now. What was it that got you thinking about these themes in the early 70s?

Probably just a lucky guess; I certainly wasn’t trying to predict the next fashionable enthusiasm. In a lot of ways, I’m not that interested in body modification; that whole Modern Primitives thing just smacks of jailhouse boredom to me. That’s why prisoners tat themselves up so much; you’ve got no other way to pass the time, so you punch a hole in yourself. But now everybody’s mom has a tattoo & a navel piercing. The girl checking out your groceries at the supermarket has two inked sleeves that would’ve been shocking a quarter-century ago, but now it’s hard to perceive any transgressive element.

The novel’s use of violence and sex is very transgressive, especially for 70s science fiction. Do you feel there is more of a place for that now in the genre than when you started writing?

The novel’s use of violence and sex is very transgressive, especially for 70s science fiction. Do you feel there is more of a place for that now in the genre than when you started writing?

Yes & no; there are a lot more things we can write about now (though with all due respect, there’s a lot of this that Theodore Sturgeon & Philip Jose Farmer were dealing with, a long time ago; they were the true pioneers) – but, increasingly so, only in certain ways. We seem to be embarking on the New Prudery – we are permitted to applaud what used to be called deviancy, but are not allowed to note the terrible, fierce & even destructive erotic power that makes it seductive in the first place. The writer who was really prescient about all this was Camille Paglia, in her essay “No Law in the Arena.” It’s a shame that’s been largely memory-holed, but there are reasons for it having happened.

Farewell Horizontal is a post apocalyptic, cyberpunk-esque novel that takes place on the side of a massive building, replete with motorcycle gangs and gas angels. Where did the idea for this book come from?

I wanted to do what I thought of as a “big landscape” novel, like Larry Niven’s Ringworld, though on a slightly smaller scale – the sort of map that has a lot of blank spaces on it, that you’re free to fill up however you please. Farewell Horizontal was originally meant to be the first book in a trilogy – something that’s typical of big landscape books – but I abandoned the notion; I was so satisfied with the novel that I didn’t want to tinker with its notions any further, at least at that time; I might go back to it, though. Some of the material for what would’ve been the sequel, I recycled into my later novel Madlands.

Madlands features a B-movie version of Los Angeles that is invading reality. What is it about the intersection of reality, dreams and media that is so compelling for science fiction?

Unfortunately, the B-movie version of Los Angeles was the Los Angeles that used to be, but which no longer exists. I miss it, and don’t consider the present-day Los Angeles to be real at all, but just a shabby backdrop for a green-screened video production, in which nobody is really anywhere; it’s all faked. To answer your question, the intersection of reality & dreams is an age-old preoccupation of fiction in general; I suspect that science fiction so often adds media to the mix because it serves as a convenient plot device for stories that revolve around an essentially faked environment that the characters find themselves stuck in. Also, for me at least, there’s a nostalgia factor that’s strong in Madlands; the old B-movie version of Los Angeles is the world from which I’ve been exiled, and to which I’m painfully unable to return.

Your novel Noir returns to cyberpunk themes, and is a brutal dissection of the inhumanity of capitalism. Would you be able to tell us a bit about it?

Your novel Noir returns to cyberpunk themes, and is a brutal dissection of the inhumanity of capitalism. Would you be able to tell us a bit about it?

I’m not so sure that Noir is an anti-capitalist novel, so much as it is, like the George Dower novels, simply anti-modernist – again, more of that Madlands nostalgia for a poorly remembered & factually, if not emotionally, inaccurate past. In terms of a particular theme, I’m still a soldier in the fight against the anti-copyright techno-jihadists – which now seems like a fight that my side has pretty much won, except for a few remaining rearguard skirmishes. Some of the anti-copyright crowd have revealed their true colors lately, such as with the so-called Electronic Frontier Foundation coming out in favor of online censorship. In that sense, Noir was prescient in detecting that some people’s definition of freedom is “You’re free to do what we want you to do.”

The influence of noir as a genre runs through your science fiction and your horror writing. What is it about the mode that keeps bringing you back to it?

Besides the nostalgia element, it’s perhaps the influence of great writers such as Jim Thompson and Cornell Woolrich, and the vision they communicated of a conspiratorial universe that inexorably tightens in a spiral around doomed and self-doomed characters. This was a genre that attracted the best American writers, and produced the best American novels – though you could certainly argue that Melville’s Moby Dick is a noir progenitor, with whales & minus the bad-girl female characters.

With writing a cyberpunk novel in 1972 and a steampunk novel in 1979, your work has always been ahead of the curve. Has this been a blessing or a curse?

People who get too far ahead always wind up with an arrow in their back. I should’ve let somebody else take the hit.

Your work spans genres, from science fiction to fantasy to cyberpunk and steampunk to horror to thrillers. How do you approach genre in your writing?

Your work spans genres, from science fiction to fantasy to cyberpunk and steampunk to horror to thrillers. How do you approach genre in your writing?

I’ve found that the best way – or at least the only way that works for me – is to not think about it. Write the story, and let the story determine what genre it fits into . . . if any.

You’ve also written extensive tie-in fiction, for Star Trek, Star Wars, Blade Runner and others. How does this differ from writing fiction set in your own original world?

With tie-in fiction, your characters lose a lot of their freedom to create themselves & act in unexpected ways, even if those would be more dramatic. But that’s the nature of the gig – you’re paid to stay within the fences. Bear in mind that even a maverick writer such as Jim Thompson had to pay the rent sometimes by writing tie-in’s; he novelized episodes of the old Ironsides television series. It’s a matter of financial reality, and as such, noir in itself.

What’s next for K. W. Jeter?

I’ve been working for some time on a big novel, which has become the whale to my Captain Ahab. We’ll see how that turn out.

Thank you K.W. Jeter for speaking with us!