The Heroine’s Journey – A study in story structures: Guest Post by Timandra Whitecastle

Today, we welcome back Timandra Whitecastle to the Hive to discuss story structures.

Before we launch into Tim’s post about the Heroine’s Journey, check out Tim’s latest novel, our SPFBO 6 Semi-Finalist Queens of the Wyrd:

Raise your shield. Defend your sisters. Prepare for battle

Half-giant Lovis and her Shieldmaiden warband were once among the fiercest warriors in Midgard. But those days are long past and now Lovis just wants to provide a safe home for herself and her daughter – that is, until her former shield-sister Solveig shows up on her doorstep with shattering news.

Solveig’s warrior daughter is trapped on the Plains of Vigrid in a siege gone ugly. Desperate to rescue her, Sol is trying to get the old warband back together again. But their glory days are a distant memory. The Shieldmaidens are Shieldmothers now, entangled in domestic obligations and ancient rivalries.

But family is everything, and Lovis was never more at home than at her shield-sisters’ side. Their road won’t be easy: old debts must be paid, wrongs must be righted, and the Nornir are always pulling on loose threads, leaving the Shieldmaidens facing the end of all Nine Realms. Ragnarok is coming, and if the Shieldmaidens can’t stop it, Lovis will lose everyone she loves…

Fate is inexorable. Wyrd bith ful araed.

Available from:

If you’ve been around on the Fantasy Hive, you might have noticed T.O. Munro’s excellent series Unseen Academic. Well, I’m a bit of an academic myself—blows dust off MA thesis—albeit a lot more sloppy and irreverent (but I have included a bibliography so witness the legitimacy!) and today’s topic is about story structure.

So, get in, learner, we’re going to EDUCATE ourselves!

First, we’ll look at where the Hero’s Journey came from, then what inspired the formulation of the Heroine’s Journey, and where that leaves us today.

ACT ONE/DEPARTURE: In which we must first lay down the framework of HOW WE GOT HERE and what the stakes are.

Once upon a time, in the last century, a story telling structure arose from the mists of time that would eventually rule them all. Nowadays we call it The Hero’s Journey, best beloved, but its origin story is the Monomyth. We’ll get to that in a moment.

First, though, what is the Hero’s Journey? The Hero’s Journey, as we understand it, is the rather formulaic fiction formula that is often used in most bestselling books and screenplays. Think Lord of the Rings (I’ll be Tolkien about it in a moment), Star Wars: A New Hope, and [insert whatever huge franchise story you enjoy the most, yes, even Fast and the Furious]. In short: Everyone loves the Hero’s Journey. (Stage whispers: Disney especially.)

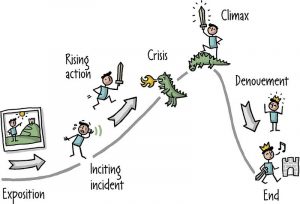

You’ll notice it follows certain beats, yes? The Call to Adventure, Crossing the Threshold, Reward, Seizing the Sword, etc you’ve heard this all before, yes? Here’s a graph that shows the rising climb of action in the Hero’s Journey:

And if you look at that graph and think hey! That looks a bit like the trajectory of the male orgasm, let me just say, I like the way you think, esteemed reader! But also: you’d be ABSOLUTELY CORRECT. So keep that in your dirty dirty mind as we progress, ok?

BACKSTORY TIME! So now that we understand what we mean when we talk about the Hero’s Journey, where does this expression The Hero’s Journey actually come from? Well, as you know, Bob, it comes from JOSEPH CAMPBELL’s obsession with the MONOMYTH, which he most famously frothed over worked through in his book The Hero With The Thousand Faces.

(If you want an accessible version of what Campbell was talking about, may I suggest you read Christopher Vogler‘s The Writer’s Journey instead? It’s relatively short and very much intended to work for screenwriting, but it works for fiction as well.)

So Campbell’s Hero was released in 1949. What’s important to note about the date of publication is that Campbell, like Tolkien, had witnessed two world wars at this point in time. And again, a bit like Tolkien (who – you’ll remember – was upset that there was no unifying lore left over from Anglo Saxon Britain and so decided he’d write one), Campbell was searching for the archetypal hero in the mythologies of the world.

Unifying theories of everything were very much a thing of that time – Einstein, Jung, Freud. In a world that must have seemed chaotic and violent and filled with trauma, we can safely assume that looking for a singular vision to pull all the scattered pieces into one, albeit large, picture is a way of dealing with said trauma.

So Campbell’s Monomyth—his ONE MYTH TO RULE THEM ALL—is called the Hero‘s Journey after the book’s titular Hero with a Thousand Faces, and it’s structured into what boils down into three acts that Campbell identified as follows: Departure/Initiation/Return. The (possibly reluctant) hero was to go on a journey – he left his tribe or kin and literally went somewhere else. He suffers a series of tests and trials through which he enters the Sacred Cave of the Mother (NOT WHAT YOU’RE THINKING! …or is it?) and gains Atonement with the Father. He who leaves must eventually return, though, but he is not the same person who left.

This Monomyth became super popular because it’s simple, yet feels true, is easily teachable, and so, so replicable. So Campbell’s structure inspired generations of storytellers like a young George Lucas, who even badgered Campbell into reading first scripts of Star Wars to make sure Padawan Lucas was DOING IT RIGHT.

Aww. Bless.

Anyway, since you are a savvy reader, I’m going to assume you noticed that there is a satisfying psychological component of the Hero’s Journey that Campbell himself was very much aware of, and I’ll get to that further down. (In fiction, this is called Foreshadowing.) For now, we depart from the First Act and enter the Second, in which our Hero’s Journey is challenged and tested to see if it is worthy.

ACT TWO/ INITIATION: In which we see the equivalent situation of the Professor having explained his awesome theory of everything to the class, only to have that ONE female student raise her hand and ask the dreaded question: WHAT ABOUT THE WOMEN?

The Monomyth’s Karen was one of Campbell’s students, Maureen Murdock. Having seen the rise of Second Wave feminism in the 60s/70s, Murdock approached Campbell to talk about the role of the Female in the Monomyth. Perhaps Campbell himself had a blind spot towards his own examinations of world mythologies? He had started with the Euro-centric mythologies he was well acquainted with (Greek in particular), and focused only on male figures. As one often does.

Murdock pointed out to him that in his structure, there were only 4 roles for women: helper/enabler of the man, an object of desire/prize to be won by the man, the thing which must be destroyed by the man, or – my personal favorite – “she’s the place people are trying to get to.” I mean … Thanks, Broseph, for explaining that people are men and women are never people. :/

He was also adamant that the Hero’s Journey couldn’t be for women. He said: the female is never the hero.

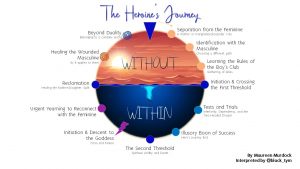

Murdock wasn’t having it. Since she had already spoken with the Manager, with no result, she set out and created her own female-centric Heroine’s Journey. One that is always an inner journey, a spiritual one. The Heroine’s Journey is about identity and self-worth and especially about being whole, Murdock postulated. It’s about balance. There may be action sequences, but a lot of the narrative drive comes from introspection and reflection. Murdock was a trained psychologist and it shows.

Credit @black_tym on Twitter

However, the inherent idea of the Heroine’s Journey is that our female hero is first the SPECIAL GIRL, she’s DIFFERENT THAN THE OTHER GIRLS and doesn’t like GIRLY STUFF at all. And her internal journey is to understand that GIRLY STUFF isn’t That Bad Actually. Maybe even useful.

Listen. Internal misogyny is a bitch sometimes. I don’t know what else to tell you.

To be fair, though, Murdock laid the groundwork for a lot of the inner character arc that we use comes from.

With me so far? Good, because the Second Act is always the longest and our Tests and Trials aren’t over yet.

Another challenger rose from the mists shrouding the lake, sword held in one hand, and Kim Hudson was her name. And for Hudson, even the Heroine’s Journey wasn’t showing the complete picture. It was STILL only one side of the whole. The attempt at the Heroine’s Journey was not a bad thing, but it’s essentially the same old story (Monomyth) dressed up in a new outfit.

Another challenger rose from the mists shrouding the lake, sword held in one hand, and Kim Hudson was her name. And for Hudson, even the Heroine’s Journey wasn’t showing the complete picture. It was STILL only one side of the whole. The attempt at the Heroine’s Journey was not a bad thing, but it’s essentially the same old story (Monomyth) dressed up in a new outfit.

So she proposed (in her book The Virgin’s Promise) that there are some components of the heroic story that are universal and not gendered. That the Hero’s external Journey and the Heroine’s internal Journey are actually two halves of a whole. And she came up with a help for screenwriters that comes very close to what we talk about today, when we talk about the Hero’s Journey in our fiction.

Hooray!

But wait! On every adventure, there is a moment of victory, only to be followed by the DARK PIT, which is the threshold to the third and Final Act. And ours is this: the problem with this is that even if we use the two structures, we’re still not actually thinking in terms of a truly feminine story structure or a story structure that doesn’t conform to any gender.

THIRD ACT/ RETURN: In which we grapple with all the things we do not know and try to find a conclusion in RETURNING (ha!) to Campbell‘s WHY of the Hero‘s Journey

Notice that all three of the Formula for Fiction Thinkers we’ve mentioned here never really went on to study anything other than the male-centric monomyth. Campbell was obsessed with it. Murdock used Campbell’s findings to create a counterpoint. And Hudson tried to meld both together into one.

Neither Campbell, nor Murdock, nor Hudson ever studied the often fragmented and strange stories that have been passed down to us from ancient times in which women were the primary actors within a story framework. There are many that Campbell simply ignored. Or overlooked. (The often murderous mother figure in Greek mythology for example…) It’s time consuming, not to mention necessitating an interdisciplinary approach, to track down and study the fragments and glimpses into other stories and story-telling traditions outside of the euro-centric, male-centric ones that survived.

In her book The Heroine’s Journey, Gail Carriger attempts this in part, and focuses on three core ancient goddesses: Demeter (Greek Mythology), Isis (Ancient Egyptian), and, older still, Inanna (Ancient Sumerian). Carriger’s book is definitely a great starting point, but since it’s primarily a writing guide/writing craft book, she doesn’t attempt an in-depth study of ancient feminine story structure.

Another great starting point is the craft book Meander. Spiral. Explode. Design and Pattern in Narrative by Jane Alison. As she writes in her introduction:

For centuries there’s been one path through fiction we’re most likely to travel—one we’re actually told to follow—and that’s the dramatic arc (…) But something that swells and tautness until climax, then collapses? Bit mascosexual, no? So many other patterns run through nature, tracing deep motions in life. Why not draw on them, too?

Remember the dick pic—I mean … the rising tension story arc at the beginning? Now, while mirroring the male ejaculation in narrative is fine, totally fine, we know that female orgasms are a thing, too, and um … often work differently than a man’s. The trajectory can be non-linear, is what I’m trying to say.

Can you imagine what stories we would tell if they mirrored the feminine pleasure instead of the fairly linear man’s?

Serialized fiction might come closest to this; with each season ending on a crest of the wave, only to begin the next season with greater strength, ever rising, until an overarching crescendo happens and the final season functions as a gentle cool down with slight tremors … ahem … where was I? Ah yes. Story structure. Just talkin‘ about good ole story structure here …

Anyway. One might point and snidely say: well, because it survived, that must mean that the male-centric, rising arc Hero’s Journey is simply the best story-telling structure we have, right?

Hmmmm.

Listen, this essay is already far too long to get into that, so let’s take a step even further back – what is the purpose of the Hero’s journey?

I mentioned before that Campbell was aware of the psychological component of his Monomyth structure. So let’s see how Campbell himself answered: the purpose of the myth, he said, is to guide humans through the stages of life, from cradle to grave.

This, I feel, is an important point. We can posit that the main universal function of the Monomyth/Hero’s Journey/Heroine’s Journey is an act of transformation (of the heroes themselves and through them, the world around them). It stands in for the drastic transformation we all undergo from childhood to adulthood and gives us a narrative structure to pattern our own lives on. From child to parent (and remember, along the way, the hero must get the blessing of the Mother and atonement from the Father, in order to proceed to become the future.)

From dependent to independent, from nurtured to nurturing, from powerless to empowered.

In conclusion, then, there remain more questions than answers.

But what have we learned, best beloved?

That there’s a disparity when writing about female characters while we’re using the predominantly masculine story framework of the Hero’s Journey.

That it can be jarring when we inadvertently create heroes out of our heroines by forcing them into a traditionally male-centric story, whether it’s the Hero’s Journey stemming from the Monomyth, or The One Girl In the Boys’ Club Heroine’s narrative.

We’ve learned that neither Campbell’s vision of the Hero’s Journey, nor Maureen Murdock’s vision of the Heroine’s Journey has remained unadulterated. We now commonly use adaptations. Indeed, our idea of the Hero/ine’s Journey is different now, more malleable, than what its originators thought it’d be.

While researching and writing this post, I became aware of the fact that any gendered story structure, be it the Hero’s or Heroine’s Journey, would exclude or at least not make room for non-binary stories. Perhaps we can and should branch out and find better fitting story structures in patterns in nature like Alison prompts? What about stories that don’t deal with the dichotomies I mentioned above, dependent to independent, nurtured to nurturing etc but transform them and show both simultaneously?

In the end, whichever story structure you use for your writing, your narrative choice informs your story and your characters.

Maybe the universality we’re looking for is simply … change?

Bibliography:

Jane Alison Meander, Spiral, Explode. Design and Pattern in Narrative. Illustrated edition. Catapult. 2019

Joseph Campbell The Hero With A Thousand Faces. Princeton University Press. 2nd edition. 1968.

Kim Hudson The Virgin‘s Promise. Writing Stories of Feminine Creative, Spiritual, and Sexual Awakening. Illustrated edition. Michael Wiese Productions. 2010.

Maureen Murdock The Heroine‘s Journey. Woman‘s Quest For Wholeness. Illustrated edition. Shambala Press. 1990.

Christopher Vogler The Writer‘s Journey. Mythic Structure for Writers. Michael Wiese Productions. 2nd edition. 1998.

A huge thank you, Timandra, for joining us today!

Timandra Whitecastle enjoys writing dark and gritty character-driven Heroic Fantasy. Her narratives leave her female characters having to make hard decisions, often dealing with themes of identity and obligations. One reader commented: Whitecastle’s characters punch you in the face and in the feels.

Timandra’s short story This War of Ours in the Art of War Charity Fantasy Anthology was nominated by the BSFA for best Short Fiction 2018. Her Norse-inspired novel Queens of the Wyrd was a 2020 SPFBO semi-finalist. Timandra has written for Grimdark Magazine as well as Black Library: Age of Sigmar.Originally hailing from Sherwood Forest, Timandra now lives in North Germany with her family and an exponentially growing collection of books.(She/her)