A MAN LIES DREAMING & THE LUNACY COMMISSION by Lavie Tidhar (BOOK REVIEWS)

“But there you are wrong, for this is no longer the world you knew, the world any of us knew. That world is dead, everything is divided, Before-Auschwitz and the Now, for there is only now, even to think of a life beyond is to indulge in fantasy. But to answer your question, to write of this Holocaust is to shout and scream, to tear and spit, let words fall like bloodied rain on the page; not with cold detachment but with fire and pain, in the language of shund, the language of shit and piss and puke, of pulp, a language of torrid covers and lurid emotions, of fantasy: this is an alien planet, Levi. This is Planet Auschwitz.”

“I believe in law, in order. There must always be order, Leni. There must always be an account.” – Wolf

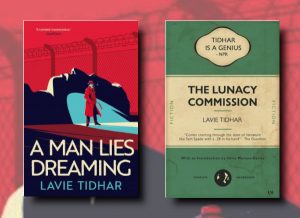

Lavie Tidhar’s masterful A Man Lies Dreaming originally came out in 2014 with Hodder & Stoughton. As a fan of Tidhar’s work I was lucky enough to read it at the time, and was immediately struck with what a powerful and disorienting work of fiction this was, a book that uses speculative fiction and alternate history as a way of talking about the Holocaust, a way of saying the unsayable and making its horror visceral and sharply felt. The novel received a handful of enthusiastic reviews and won the Jerwood Fiction Uncovered Prize, but never quite tipped over into having the mainstream respect and attention it so clearly deserved. Flash forward seven years, and in 2021 A Man Lies Dreaming is being reissued by Head Of Zeus, hopefully to bring it to a whole new audience. Simultaneously, JABberwocky Literary Agency have collected the linked short stories that Tidhar has written since the publication of the original book into a single volume, The Lunacy Commission, which acts as a companion volume to the novel proper. Rereading Tidhar’s masterpiece now is a very different experience. The novel was written considerably before MAGA and Brexit, yet Tidhar’s book is as much about the rise of a pernicious, British strain of fascism that anticipated these populist nationalist movements. It’s hard not to read A Man Lies Dreaming as a frighteningly prescient warning about our complacency in the face of this populist nationalism and the horrible places it would inevitably lead. But perhaps the benefit of hindsight will convince more people that Tidhar truly is one of the key literary voices of the modern age.

Tidhar is the descendent of survivors from Auschwitz, so the question of how to write about the horrors of the Holocaust is a personal part of his Jewish heritage. How does one portray the horrors of history in a way that captures the unspeakable reality of it whilst avoiding reproducing those horrendous images to the point where they become simply the cliché of a thousand Oscar-winning films, important snapshots of history numbly devoid of the very human revulsion and horror we should feel at this ghastly mechanised mass-extermination of human life? Tidhar’s answer is to turn to pulp fiction. A Man Lies Dreaming transports us to an alternate 1939, in which Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in the early 30s was thwarted by the communists winning the 1933 election, resulting in the one-time leader of the Nazi party eking out a precarious existence as a private eye in the streets of London, going by his old nickname Wolf. Jewish femme fatale Isabella Rubenstein walks into Wolf’s office with a case for him, to find her missing sister who has disappeared after being smuggled out of Germany. What follows is a series of darkly tragicomic farces as Wolf suffers various humiliations whilst trying to solve the case, in the best tradition of Raymond Chandler or Dashiell Hammett. But all is not as straightforward as it seems – all of this is happening in the mind of Shomer, former writer of shund or cheap Yiddish pulp fiction, who is slowly dying along with millions of other Jews in the concentration camp Auschwitz, in a reality much closer to our own.

Tidhar is the descendent of survivors from Auschwitz, so the question of how to write about the horrors of the Holocaust is a personal part of his Jewish heritage. How does one portray the horrors of history in a way that captures the unspeakable reality of it whilst avoiding reproducing those horrendous images to the point where they become simply the cliché of a thousand Oscar-winning films, important snapshots of history numbly devoid of the very human revulsion and horror we should feel at this ghastly mechanised mass-extermination of human life? Tidhar’s answer is to turn to pulp fiction. A Man Lies Dreaming transports us to an alternate 1939, in which Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in the early 30s was thwarted by the communists winning the 1933 election, resulting in the one-time leader of the Nazi party eking out a precarious existence as a private eye in the streets of London, going by his old nickname Wolf. Jewish femme fatale Isabella Rubenstein walks into Wolf’s office with a case for him, to find her missing sister who has disappeared after being smuggled out of Germany. What follows is a series of darkly tragicomic farces as Wolf suffers various humiliations whilst trying to solve the case, in the best tradition of Raymond Chandler or Dashiell Hammett. But all is not as straightforward as it seems – all of this is happening in the mind of Shomer, former writer of shund or cheap Yiddish pulp fiction, who is slowly dying along with millions of other Jews in the concentration camp Auschwitz, in a reality much closer to our own.

Tidhar’s peculiar genius comes from how he takes the central conceit of Adolf Hitler as a noir detective, something that sounds like it should only be good for a cheap and somewhat tasteless laugh, and manages to produce something both entertaining and profound from it. Wolf’s alternate history noir escapades are contextualised by the fact that this is being made up by Shomer in Auschwitz because, with his family dead, his people being systematically murdered, and the clock of his remaining life winding down towards his own inevitable extermination, fantasy is literally all he has left. Thus what could otherwise be misconstrued as trivial gains a real pathos. Shomer imagines Wolf suffering through various misadventures, from being forcibly circumcised by Jewish gangsters to being beaten up by everyone from cops to Britain’s own fascists. Wolf encounters various other members of the Nazi party, from Ilse Koch, the sadistic camp commander of Buchenwald to Klaus Barbie, the Butcher of Lyon, to Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi’s propaganda minister, and Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s second-in-command, all of whom are reduced to what they would have been without the official state backing of the Nazis – vicious small-time thugs. These daydreams are not just a perfectly understandable revenge fantasy on the part of Shomer, an attempt to see justice meted out to people beyond Shomer’s power, but they also ask the question, who are these people who were behind the Holocaust? Shomer’s fantasies, in their own back-handed way, extend a simple human courtesy that the Jews were denied by the faceless automated mass-murder of the extermination camps. What kind of person cannot even conceive of the people they hate as fellow human beings with their own interior lives? Shomer wonders:

“Shomer turns, blinks. Thinks of him, in bed: does he ever think of them, in the camp? Does he imagine what they feel, what they miss, how they die? Does he know them at all, beyond the numbers on their arms? And he pictures a book of accounts, filled with rows and rows of endless numbers, a book as large as the world.”

A Man Lies Dreaming also critiques the noir genre whilst it pastiches it. It’s clear from the breathless flood of noir signifiers throughout the book that Tidhar has a deep and abiding love of the form. But also he is aware of the genre’s issues. The novel opens with the line, from Wolf’s diary, “She had the face of an intelligent Jewess.” The racism is what one would expect from Wolf, but it is also a conscious echo of a near-identical line in Raymond Chandler’s noir classic The Big Sleep (1939). By having Wolf echo Chandler’s casual racism, Tidhar highlights the outdated attitudes that prevail in many of these classic pulp tales, that we would rightly recoil from today. In a weird way, Wolf makes the perfect noir detective. The noir detective is frequently a downtrodden, deeply broken man, one who has a strict moral code that is at odd with the world around him that drives him to try to restore his sense of order to the world. The same could be said of fascist dictators. Wolf’s misanthropic world view echoes that of hardboiled noir heroes like Hammett’s Sam Spader, and brings to mind Alan Moore’s characterisation of Rorschach in the classic graphic novel Watchmen (1986-87). In much the same way that Rorschach’s abusive upbringing and personal disfunction lead him to become a deeply racist, misogynistic and paranoid man who clings to his own sense of morality cause it’s the only way he can make sense of the world, Tidhar shows us the same tendencies in Wolf.

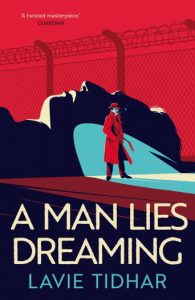

But perhaps the most chilling aspect of A Man Lies Dreaming when read today is the way it describes a very British kind of fascism. In the alternate history Shomer imagines, the communists may have put a stop to the Nazi party in Germany, but the same forces that led to the ferment of fascism in Germany are spreading across Europe, making themselves felt particularly strongly in the UK. In much the same way that recontextualising the Nazi’s most brutal monsters as mere two-bit thugs shows there’s nothing inherently special about them, similarly Tidhar warns us that the conditions for the rise of fascism are not unique to Germany. Wolf’s London is one that has reacted with fear and hatred towards the immigrants driven from Europe by the collapse of Germany, leading Wolf himself, as a German immigrant trying to earn a living in London, to become the source of the vitriol of British fascists. Over the course of the book, we see Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists, replicate many of Wolf’s old tricks – commented on hilariously by Wolf himself – to rise to a comparable position of power as the prime minister of the UK. Mosley’s upper class British buffoon persona hides a truly nasty and hateful power-hungry demagogue, a toxic element of the British upper class all too familiar to us today. Wolf has various meetings with Virgil, an American secret agent who wants to reinstall the fascists in Germany to stop the rise of communism. In a particularly memorable scene, Virgil promises to make Wolf great again. I had to check that this piece of dialogue was in fact unchanged from my first edition, so great appear the coincidences. But the line is from Tidhar’s original text. A Man Lies Dreaming these days stands as a terrifying warning to the UK and the US, one we weren’t ready to listen to at the time. One can only hope that Head Of Zeus’ timely new reissue, in a handsome edition with glorious pulp cover art by Levente Szabo, means that Tidhar’s masterful novel reaches more people this time round.

But perhaps the most chilling aspect of A Man Lies Dreaming when read today is the way it describes a very British kind of fascism. In the alternate history Shomer imagines, the communists may have put a stop to the Nazi party in Germany, but the same forces that led to the ferment of fascism in Germany are spreading across Europe, making themselves felt particularly strongly in the UK. In much the same way that recontextualising the Nazi’s most brutal monsters as mere two-bit thugs shows there’s nothing inherently special about them, similarly Tidhar warns us that the conditions for the rise of fascism are not unique to Germany. Wolf’s London is one that has reacted with fear and hatred towards the immigrants driven from Europe by the collapse of Germany, leading Wolf himself, as a German immigrant trying to earn a living in London, to become the source of the vitriol of British fascists. Over the course of the book, we see Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists, replicate many of Wolf’s old tricks – commented on hilariously by Wolf himself – to rise to a comparable position of power as the prime minister of the UK. Mosley’s upper class British buffoon persona hides a truly nasty and hateful power-hungry demagogue, a toxic element of the British upper class all too familiar to us today. Wolf has various meetings with Virgil, an American secret agent who wants to reinstall the fascists in Germany to stop the rise of communism. In a particularly memorable scene, Virgil promises to make Wolf great again. I had to check that this piece of dialogue was in fact unchanged from my first edition, so great appear the coincidences. But the line is from Tidhar’s original text. A Man Lies Dreaming these days stands as a terrifying warning to the UK and the US, one we weren’t ready to listen to at the time. One can only hope that Head Of Zeus’ timely new reissue, in a handsome edition with glorious pulp cover art by Levente Szabo, means that Tidhar’s masterful novel reaches more people this time round.

A Man Lies Dreaming is a masterpiece in and of itself, but as a long-time fan of the book it’s a very nice bonus to have Tidhar’s extra Wolf and Shomer stories in The Lunacy Commission. These stories are set before the apocalyptic events of the novel proper, and give us a glimpse into both Shomer’s life prior to the concentration camp. Here we see a Shomer living with his family, determined to enjoy the love and happiness they have left to him as he becomes more and more aware of the terrible fate awaiting so many Jews in Europe. Once again, the theme of fantasy as a necessary form of escape when there is nothing else one can do runs through these stories. The stories also allow Tidhar to explore the aspects of Nazism he didn’t get round to in the book, from the loathsome William Joyce, better known as Lord Haw-Haw, a member of the British Union of Fascists who wound up broadcasting Nazi propaganda in Germany during the war in ‘Red Christmas’ to Heinrich Himmler’s well-known fascination with the occult in ‘The Spear of Destiny’. The title story ‘The Lunacy Commission’ explores the complicity of German nurses like Pauline Kneissler in the Nazis’ involuntary euthanasia programme. The stories are all fantastic and worthwhile additions to A Man Lies Dreaming, and Sarah Anne Langton’s fantastic cover amusingly pastiches cheap beaten-up Penguin crime paperbacks from the 50s and 60s, but frustratingly the editing on the text is a mess, with Himmler’s name spelled wrong multiple times, beginnings of sentences uncapitalised and one story given the wrong name on its title page. A shame as this mars an otherwise fantastic collection.