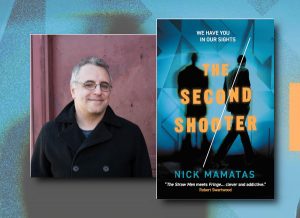

Interview with Nick Mamatas (THE SECOND SHOOTER)

Nick Mamatas is a unique author, who has been doing his own individual take on science fiction, fantasy and horror for 20 years. His novel Move Under Ground (2005), which combines the Beat poetry of Jack Kerouac with the cosmic horror of H. P. Lovecraft, became a cult hit. Mamatas’ blend of deft characterisation and sharply realised satire can be keenly felt across much of his work, including I Am Providence (2016), a murder mystery set in a Lovecraft fan convention, and The Last Weekend: A Novel of Zombies, Booze and Power Tools (2014), in which a failed science fiction writer must stave off the zombie apocalypse. His latest novel, The Second Shooter (2021), comes out later this year with Solaris, and is a pointed exploration of conspiracy theories and weird politics in a SF/fantasy thriller mode. As well as writing novels and short stories, Mamatas is also a prolific editor. He was the editor for Haika Soru, Viz Media’s essential imprint for Japanese translated speculative fiction, and has edited many anthologies. Nick Mamatas was kind eoungh to speak to The Fantasy Hive via Zoom.

Your new novel, The Second Shooter, is coming out with Solaris in November, would you be able to tell us a bit about it?

The Second Shooter is about a radical journalist who is writing a book about the phenomenon of a second shooter. When there are mass shooting events, the early news stories report more than one shooter. Almost invariably, there isn’t more than one shooter in real life. It’s just confusion from echoes, from the police shooting back, and from the fact that eyewitnesses are not very reliable. But in this setting of the story, there are second shooters and they do vanish afterward, and evidence of them vanishes afterward. And basically, it is the story of this fellow Michael Karras, who is trying to figure out what’s behind this phenomenon, and also deals with conspiracy theories and weird subcultures and unusual politics. So it’s a speculative, or fantasy, thriller.

Conspiracy theories and weird politics is particularly relevant right now with the whole fake news and the sheer amount of misinformation that we get from things like Facebook. Was the current political climate something that fed into your idea when writing the book?

Yes, I started writing that book in 2016, after Brexit but before Trump. And then I had to put the book aside to do some other projects. By the time we had sold the book to Solaris, early last year, everything had changed. When you sell a book, it’s after writing 25,000 words and a synopsis of the rest. And that synopsis just had to go out the window. So I was very late with getting the book in because I had to rewrite the third act entirely to adapt to the world of QAnon, and “Trump won” election conspiracy theories, and satanic blood-drinking billionaires and all the other stuff that came up between the genesis of the project and its completion. But I had to play catch up. One of the horrible possibilities authors who write near-future novels. Will reality get crazier than you are? And this time, yes, it did!

I was secondarily influenced by Charlie Stross, the science fiction writer, who had tweeted out while I was writing this third act, that science fiction writers mustn’t write about conspiracy theories anymore. We can’t do it because we’ll be undermining reality itself and giving people encouragement to believe in them. I said, I don’t think that’s true. But it’s worth thinking about. And so that was a secondary thing. When I’m writing this, am I saying things in my writing that can explain conspiracy theories? Or about who believes in them and to what extent they do and their politics and their social lives? Without just making it so simple, without saying that only idiots believe in conspiracy theories. Because that’s not the case. Very intelligent people believe stupid things all the time. And also without making it easy to say, yeah, well, of course, some of these conspiracies must be true. It was a narrow path to walk.

Yeah, it’s a delicate balance for sure.

Exactly.

And there’s that thing running throughout the book that Karras says multiple times that there’s something kind of comforting about these conspiracy theories because if you believe that all the mass shootings and all the terrorist attacks are false flag operations, then there have been zero terrorist attacks and zero mass shootings for the last however many years. There’re the elements of comfort that conspiracy theorists cling to, which is part of the psychology of it.

And there’s that thing running throughout the book that Karras says multiple times that there’s something kind of comforting about these conspiracy theories because if you believe that all the mass shootings and all the terrorist attacks are false flag operations, then there have been zero terrorist attacks and zero mass shootings for the last however many years. There’re the elements of comfort that conspiracy theorists cling to, which is part of the psychology of it.

And they personalize this thing. Instead of talking about say, capitalism, they’ll be talking about a handful of secret “international bankers”—pure anti-Semitic conspiracy theories. Instead of talking about the persistence of racism, they’ll talk about how people are being driven apart by fake news. And so we can have enemies that are flesh and blood enemies, that we can point to and say, “Ah that’s a bad person!” If I tweet something bad about this person we can win, and reclaim society for ourselves! But systems are necessarily faceless. I mean, of course, there are billionaires who manipulate the economy. But their personal psychology is only a minor part of it; it’s the system. So conspiracy theory avoids systematic thinking and makes thinking either metaphysical and religious, or personal. And those problems are easy to solve, or someone else can solve them or you. So if you believe that Jesus wants Trump to be president, well, all you got to really do is wait for Jesus to come in and solve all your problems and make Trump the president again. If you believe that George Soros is to blame, well, you can keep track of George Soros and what he’s after and what he’s up to, and it makes things much simpler for the worried believer in conspiracy theories.

There seems to be a weird correlation that the more access we have to information, the more conspiracy theories and misinformation thrive. You think that having more access to more information would be the death of conspiracy theories.

It’s a weird thing, because, of course, the mainstream also lies all the time. We were told for many years that Iraq had an ongoing nuclear weapons programme, ongoing weapons of mass destruction programmes, and it was all false. Eventually, they did actually find a warehouse containing old things from the 1990s. Essentially, an inventory error, that wasn’t an ongoing program and didn’t work at all. It wasn’t worth the murder of somewhere along the lines of half a million people between outright war and malnutrition and sanctions afterward. And I know that The Times went along with it, CNN went along with it, all the mainstream sources went along with this for a long time.

These days, of course, we focus a lot on the right wing conspiracy theories. But the left wing has conspiracy theories too, like the idea 9/11 was an inside job or that it was faked, CIA blew up the buildings. Which is just impossible, but in the Democratic Party milieu in the early 2000s, it was ubiquitous. Not that everyone believed it, but that you couldn’t go to a party meeting or have a liberal online bulletin board or blog that didn’t have these in the comment section. “Well, what about 9/11? What about Tower Seven? What about how Willie Brown, the former mayor of San Francisco, had been warned?” And all these crazy things would come up and people believe it. And there’s really nowhere to turn to because we’re not experts. We don’t know things and we so we just trust experts, or find our own experts. And say, well, I believe this expert who happens to already agree with me. Because it’s easy to find a doctor or nurse who doesn’t believe in COVID. It’s easy to find a physicist—usually not an architect—who thinks you can detonate a skyscraper by sneaking dynamite onto the third floor. So we’re kind of stuck.

As in a lot of your books, The Second Shooter uses genre conventions, in this case fantasy thriller, to engage with these ideas. So what makes genre fiction such a good tool for engaging with these ideas?

Great questions. I don’t know if I pick genre fiction to do it purposefully. I think partially it is that there is a satirical strain inside genre. Especially science fiction and fantasy often have satirical elements. And as a kid, I was most attracted to that kind of science fiction and fantasy. When I started reading more mainstream science fiction and fantasy I was very surprised to find out that say, Robert Heinlein, believed the stuff in his books. I thought he was kidding—that they were just thought experiments! And then I went to conventions and would meet these serious-minded fans, and oh my god, not only does he believe it, you believe it! It was just mind-blowing that people took this stuff seriously! Or unironically seriously.

Genre fiction allows for two traits. You have the generic conventions of the plot and reversals of fortune that keep you reading. And because it’s out of the mainstream, by definition, you’re allowed to have unusual people in it. Unusual, weird characters. And I like characters who have weird beliefs and marginal beliefs, and who have had unusual experiences. Science fiction and fantasy is useful for exploring radical political, or the particular role of politics, or wherever you want to phrase it, in a way that literary realism isn’t. And in fact, when you find literary realist books that do this kind of thing, they often involve a science fictional element. So in something like Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections, you have the essentially magical drug, and that solves a lot of psychological problems. Or now a lot of mainstream writers are writing about climate fiction. Where it’s a day-after-tomorrow scenario, the city that the sea really did drown forever, there’s no more New Orleans, and that kind of thing. So now we’re going to get a lot of plague novels, a lot of economic collapse novels that utilize science fiction, fantasy elements. Or probably science fiction elements, with the occasional fantasy element like a ghost or something as well. So realism is the only way to look at the recent past. Realism is great for writing about your own childhood, or your own college years, or your own unsuccessful first marriage. But when you want to look to what’s going to happen in 18 months, you don’t know. And the proof of that is the last 18 months we’ve all lived through.

Well, yeah, absolutely.

I didn’t know what Zoom was 18 months ago, and here I am talking to you in Liverpool with it.

It had almost become a cliche before the pandemic to say that the present day is becoming more and more science fictional. And that’s before we wound up in this massive, global pandemic.

Exactly. And there have been ideas about for a long time, like cyberpunk books I know. Here’s the futures it’s unevenly distributed, as William Gibson said. But of course, people say that all the time. Leon Trotsky used to say that. He had a different version of it—combined and uneven development—where capital was developing everywhere, but not evenly. And so in places where there wasn’t full capitalism yet would have a different kind of struggle toward the future, toward socialism. So this idea of things changing rapidly, and unevenly is the long-standing one. It’s not one that literary realism can really handle very well. So you’d have to go to postmodernism or genre fiction. So I do both!

Your novel I Am Providence, about a murder mystery set at the Lovecraft fan convention, came out a couple of years ago. Lovecraft is a figure that you you keep returning to in your work. I really like your piece “Why Write Lovecraftian Fiction?” where you talk about the contradictions of all the horrible stuff that we know about Lovecraft, and yet we still find his creations so appealing? I wanted to ask you about your relationship with Lovecraft’s work and how you approach that ambiguity.

Well, I think there are two axes involved here. I know many people who are lovely individuals, have all the right politics, activate themselves to become active in their community helping the hungry, fighting injustice and war. And they say, “Oh, I’m a writer too. Can you read some of my work?” And I do, it’s awful. It’s just so much garbage, man! For a variety of reasons, including just not having written enough yet and read enough yet, to being explicitly didactic, to the point where the entertainment value is missing. Or it’s their own anxieties about writing, which is kind of like when people say, “Oh, I don’t know if I want to work out, I don’t want to be one of those big bodybuilders.” You won’t, don’t worry about it. “I don’t know I want to sell out and have a bestselling novel…” Don’t worry about it; it’s not going to happen, kid. Just write whenever you want. Just because you’re good, doesn’t mean you’re good. We have to separate the good artist from the bad art.

And then we have people like Lovecraft who had very odious ideas about Jewish people, about people of colour, about immigrants. If I’m walking down the street in America, for the most part, people would say oh there’s a white guy, but if I walk down the street in Lovecraft’s time, many would say that I was not white, and Lovecraft certainly would not think I was white. And he would not like my father, and he would not like my mother, coming over here and doing whatever they’re doing and taking jobs, them celebrating Easter on some other Sunday, speaking another language. But nonetheless, even with those ideas, his vision of the universe was very interesting. And his turns of phrase are very interesting. And you can separate the good art from the bad artist. Now, of course, there are often issues about genetic degradation in Lovecraft. Not all of the stories deal with that kind of thing. But what makes it powerful is that he lived his fears. He was really afraid of that stuff. And that real fear shows up in his stories. So in a weird way, you can talk about modern writers, and their racism and reactionary ideas make them less interesting writers, because they’re just on a soapbox, spreading politics as opposed to spreading emotional content. Lovecraft was really laying his anxieties out on the page. And we can still read that stuff and be shocked and be surprised and be horrified and experienced the frisson of terror that’s the joy of it, but we don’t need to adopt his opinion to get that working. Whereas if I’m reading Dan Simmons, and it’s a book about those terrible Arabs or that kind of thing, I can’t separate it out. It’s explicitly, and merely, political in a way that Lovecraft isn’t.

Your older books have engaged with Lovecraft as well, like Move Under Ground, which is a mix between the Beat poets and Lovecraft. Which on the surface of it is not a stylistic combination that you think would work, but it does! So where did the idea come from to put those two disparate things together?

Well, this is a long time ago. It was totally mercenary! I had a friend named Joi Brozek, who is a writer, and she was writing in her journal one day, and some guy came up to hit on her and said, “Oh, I’m writing a book too!” So she said, “Oh, what is the book?” And he didn’t have a book. So he’s thinking about it, and he goes, “Oh, I guess it’s kind of like Kerouac’s On The Road meets surreal…realism?” I thought that sounded good, I want to read that! And then I was at St. Mark’s Bookshop in New York, which was a bookshop with radical pretensions, and a large selection of magazines and underground stuff and cult material and also mainstream books. I was at the bargain table because I didn’t have any money. And I saw both a collection of Kerouac’s letters with a bunch of Lovecraft’s letters for sale on the table. And not realising why they were on the bargain shelf I thought to myself, Aha, these guys must be really popular. Because people even want to read their letters, once they’ve read their stories. I’ll take that idea that I heard from Joi, and squish them together and make it Kerouac meets Lovecraft. Everyone who loves Kerouac will buy the book and everyone who loves Lovecraft will buy the book!

Well, this is a long time ago. It was totally mercenary! I had a friend named Joi Brozek, who is a writer, and she was writing in her journal one day, and some guy came up to hit on her and said, “Oh, I’m writing a book too!” So she said, “Oh, what is the book?” And he didn’t have a book. So he’s thinking about it, and he goes, “Oh, I guess it’s kind of like Kerouac’s On The Road meets surreal…realism?” I thought that sounded good, I want to read that! And then I was at St. Mark’s Bookshop in New York, which was a bookshop with radical pretensions, and a large selection of magazines and underground stuff and cult material and also mainstream books. I was at the bargain table because I didn’t have any money. And I saw both a collection of Kerouac’s letters with a bunch of Lovecraft’s letters for sale on the table. And not realising why they were on the bargain shelf I thought to myself, Aha, these guys must be really popular. Because people even want to read their letters, once they’ve read their stories. I’ll take that idea that I heard from Joi, and squish them together and make it Kerouac meets Lovecraft. Everyone who loves Kerouac will buy the book and everyone who loves Lovecraft will buy the book!

And that was false. That did not happen. In fact, it was everyone who loves Kerouac AND Lovecraft bought the book. A very small Venn diagram overlap there. But having said that, that was 2004. And it had sort of a cult following and was well reviewed. And many years later, this guy, Peter, who was a college student, or a kid, when he read the book, and it kind of blew his mind and changed his life and whatnot, got a job in publishing. And out of the blue two years ago he contacted me and said, “Hey is Move Under Ground out of print? I can bring it back into print!” And so last year, we had a new Dover Publications edition of Move Under Ground out with corrected text and a nice new cover that’s white and doesn’t smudge as easily if you handle it without washing your hands. And thankfully, because of COVID everyone’s washing their hands all the time, right? So I had written a cult novel; and when you write a cult novel that lasts 16 years and that someone who was a kid at that time gets into publishing partially because of the book to bring it back out, that’s a success in my book.

As well as writing you also do work editing. You were in charge of Haikasoru, the Japanese science fiction in translation line from VIZ…

Yep, I did that. 2008 to 2019. 11 years, which is a pretty good run in publishing. And we had some bestsellers, we had a book that became a film. The book All You Need Is Kill became the film Edge Of Tomorrow. And we got a Hugo Award for Ken Liu’s “Mono No Aware”, one of the stories we published in an anthology called The Future Is Japanese. And then we parted ways amicably. And now I’ve done some other editing since then. Speaking of Lovecraft, I did a book for Dover called Wonder and Glory Forever, which is awe-inspiring Lovecraftian fiction. Because Lovecraft is all about doom and gloom, but there’s also the element of the sublime and the spectacular. And the stories I chose represent that. So we had stories by Molly Tanzer, Victor LaValle, Livia Llewellyn, Michael Cisco.

We reprinted a classic by Lovecraft, and a classic by Clark Ashton Smith, to sort of reconceptualize Lovecraft as someone who writes about the sublime, who is awe-struck by things. And that same contradiction we were talking about before comes up again. Like in ‘Shadow Over Innsmouth’, the main character is repulsed by this idea of becoming – it’s not a spoiler, it’s a ninety-year-old story! – a Deep One, a sea creature. But in the end the character thinks, this is great, down here in the water. “Wonder and glory forever!” Obviously, the end is supposed to be terrifying, the protagonist loses himself, his humanity. But also it is kind of great. I can hang out forever! I mean, wouldn’t you want to just be able to breathe underwater and see everything down there? Of course you would, I would. And you get to meet your own God, instead of having this distant God we never get to talk to up here in the surface world. So the horror of genetic degeneration ends up being pretty cool. And that’s part of what makes Lovecraft good. There’s more than one layer to him, more than one level to him. And this book, Wonder And Glory Forever, is exploring a new level that is not often discussed. I hope to get some more editorial projects going pretty soon.

Cool. And just to bring this to a close, what are you working on next?

Some short stories. One just came out in September. I have a short story called ‘The Man You Flee At Parties’ in the anthology Out Of The Ruins edited by Preston Grassman, which was interesting, because it’s a post-apocalyptic anthology. But when I was first solicited, it was only an anthology about future cities, and it became a post-apocalyptic anthology because everybody wrote about crapsack futures. So after eight months or nine months, Preston contacted me again and said something like “Hey, are you still working on this story? Can it be in a shitty future, because all the other stories are.” So that was fun. And I’m still working on and I’m trying to find a publisher for a book – if you happen to be a publisher with a lot of money, or even a little money, you can write to me! –that is a posthuman post-singularity version of Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

Thank you Nick Mamatas for speaking with us!

The Second Shooter is out from Solaris on 9th November.