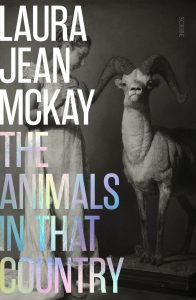

THE ANIMALS IN THAT COUNTRY by Laura Jean McKay (BOOK REVIEW)

“Animals are straight up like that. It’s people you have to watch out for.”

“Birds are making nonsensical sounds above, but all around me, trails of glowing messages have been laid out overnight. In stench, in calls, in piss, in tracks, in blood, in shit, in sex, in bodies. A big boy wallaroo has rubbed his scent, slick as oil, over the grass at the road edge. It’s like running alongside a urinal in a pub. Piss cakes wafting from the bottom of yellow streams. Shake my stupid head to clear it of the meanings, but they form out of hops, barks, and whiffs. I see these words as: King and ours. Bits and pieces, no damned order or sense. A drunk on the street. Kimberly talking in her sleep. Until they close like clouds, moving from blobs to ships in full sail, and I see the sense, loud and clear:

Fuck me, I’m

a King.”

Laura Jean McKay’s The Animals In That Country (2020) deservedly won the 2021 Arthur C. Clarke Award. McKay’s novel about a pandemic which causes humans and animals to be able to talk to each other is a startlingly original exploration of human/animal communication, a powerful and discomforting read that asks probing questions about what it means to be human. Talking animals is such a staple of children’s fiction and fantasy, yet McKay manages to make it strange and compelling by forcing us to face just how different animals’ thought processes may be from ours, to accept animals on their own terms as autonomous beings with different needs, wants and agendas from us. McKay contrasts her animals with believable, well-rounded and deeply unlikeable human characters, people suffering from the inability to communicate with each other. On top of all of this, we get McKay’s remarkable prose, a hallucinogenic evocation of the Australian landscape and a moving and all-too-familiar portrayal of society slowly collapsing at the seams. Combined together, this makes The Animals In That Country absolutely essential reading for anyone interested in what speculative fiction can do at its most bold and original.

Jean works as a guide at an Australian wildlife park, half-heartedly hiding her drinking problem from daughter-in-law and park manager Angela so that she can spend time with her granddaughter Kimberly and perhaps one day be promoted to ranger. All this changes when a pandemic spreads across the country, bringing with it the dubious gift of being able to understand animals and be understood by them in turn. Jean’s son Lee, infected and dreaming of communication with whales, turns up at the park as Jean is trying to look after the animals in the increasing chaos, and takes Kimberly with him on a dangerous and ill-advised journey southwards. Jean must track down her missing granddaughter, with the help of Sue the dingo, before her son and granddaughter are consumed in the chaos. But Jean now also has the disease, and communicating with the animals turns out to be more disturbing and upsetting than she could possibly have anticipated.

Jean works as a guide at an Australian wildlife park, half-heartedly hiding her drinking problem from daughter-in-law and park manager Angela so that she can spend time with her granddaughter Kimberly and perhaps one day be promoted to ranger. All this changes when a pandemic spreads across the country, bringing with it the dubious gift of being able to understand animals and be understood by them in turn. Jean’s son Lee, infected and dreaming of communication with whales, turns up at the park as Jean is trying to look after the animals in the increasing chaos, and takes Kimberly with him on a dangerous and ill-advised journey southwards. Jean must track down her missing granddaughter, with the help of Sue the dingo, before her son and granddaughter are consumed in the chaos. But Jean now also has the disease, and communicating with the animals turns out to be more disturbing and upsetting than she could possibly have anticipated.

McKay’s animals are gloriously strange, and communicating with them is like an encounter with the alien. Near the beginning of the book, Ange calls out Jean’s tendency to anthropomorphise animals, saying it’s dangerous because it prevents her from seeing the reality of the animals. Unlike the anthropomorphised talking animals we frequently encounter in fiction, fairy tale or fable, who represent a part of humanity reflected back at us, McKay’s animals communicate through a bizarre, elliptical kind of poetry, one called into existence not just by vocalisations but by gestures, scents, pheromones and actions. It’s difficult to understand, some of it sounding like chatter, but concentrate and you can pick up the sense of it. Like listening into one side of a phone call, there’s a sense of only hearing part of a conversation, but it’s clearly an intelligent conversation between beings with their own form of language and cultural contexts. Just one that is entirely different to ours. For example, here’s Sue the dingo talking to Jean about how Jean reared her:

“It’s a

warm sky

fire. The hot

meat mother.

Oh.

I taste the

Pack. I smell it

(Yesterday).”

Sue, being a dingo and therefore a mammal, is relatively close to humans, therefore Jean is able to communicate with her fairly early on in the process of the infection. For animals further from humanity, such as birds, then fish, and finally insects, it takes longer for the infection to be able to translate them, and when it does, they are so different from us it is even more difficult to make sense out of what they are saying.

McKay uses the zooflu pandemic to explore the various ways in which animals are entwined in our lives, and the various ways in which we isolate ourselves from the non-human world. The Australian wilderness is full of chattering birds, but the cities and countryside alike are full of buzzing insects, there are mice and rats and other vermin living in conjunction with people. There are the wild animals who see us as predator or prey, there are the animals in the park like Sue who are in between their wild ancestors and domesticated animals. Then there are the animals we choose to live with, cats and dogs and other pets, and the animals we choose to eat, like pigs and cows. The Animals In That Country forces us to confront the artificiality of our relationships with all these animals, the ways in which we do and don’t grant them agency, and how our very self-image is disrupted when the animals can talk back to us, can show us what they really think of us.

If humans have difficulty communicating with animals, that’s nothing compared to the difficulty humans have communicating with each other. Jean is a challenging character. She is impulsive, illogical and destructive, a woman who has alienated every person she has any kind of relationship with. This makes her difficult to like, but McKay makes her thoroughly compelling. As the story progresses, we learn more and more about why Jean is the way she is, what causes her to burn every bridge between her and other people, and we wind up understanding and feeling sorry for her. She is at the centre of a truly dysfunctional network of people, and none of them, from Angela to Lee to her various co-workers or people she encounters on the road, come out of it looking good. In the end, perhaps the true nature of the human condition is this terrible loneliness, that comes from alienating everyone you’ve ever known.

The novel takes us on a post-apocalyptic road trip, but one that’s distinct from any the reader may have encountered before. McKay’s prose is muscular and lean, and the novel features powerful and striking images of a world collapsing, awash with human detritus as the civilisation we are so proud of crumbles around us. The Australian landscape is a key part of the novel, and the book goes beyond the human and the animal to explore our soured relationship with the ecosystems we are casually destroying. It’s a bleak and unforgiving book, one that provides no easy answers to the uncomfortable questions it brings to the reader. But it is leavened with dark humour throughout, and Jean’s wonderfully sardonic narrative voice. The highest compliments I can pay to The Animals In That Country are that McKay has created a book unlike anything I have ever read before, and one which will continue to haunt and trouble me for some time. It’s a fantastic choice for Clarke winner, and I can only hope this will encourage more and more people to experience this extraordinary book.