CURRENT RESEARCH IN SPECULATIVE FICTION (CRSF) 30th June to 1st July – Conference Report by T.O.Munro

Delegates hailing from France, Spain and Italy joined UK based delegates and online participants from as far afield as California, Dehli and Australia at CRSF’s first ever hybrid event.

CRSF has been held annually since 2011 but the pandemic had restricted post-2019 events to an online format only. The hybrid nature of this year’s conference allowed a welcome return to the conviviality of face-to-face gatherings alongside the versatility and reach of online zoom meetings.

CRSF team, Jonathan Thornton, David Tierney, Lucy Nield, Alex Veregan, Jordan Casstles, (Eamon Reid – not shown)

While some early hybrid events may have struggled to manage the choreographic and technical challenges that hybridity presents, the CRSF team pretty much nailed those difficulties down. One key element of the event’s success was having a sufficiently large team to allow separation of the technical management role from that of academic chair in each of the sessions. Overcoming the vagaries of zoom and the discombobulation of time zone differences, delegates enjoyed two days of panel discussions, key notes and paper presentations in the impressive setting of Liverpool University’s School of the Arts Library – and associated breakout rooms.

For its 11th year CRSF set out to explore a breadth of themes around communication, personhood and their expression at the boundaries between human and non-human. The opening panel brought together four authors who had used the vehicle of speculative fiction to consider how animals are enhanced – or uplifted – by the effects of technology or a virus might interact with their human supposed masters.

In a fascinating discussion, Adrian Tchaikovsky, Adam Roberts, Laura Jean Mckay and Gareth L Powell explained how they had sought to give their creations a unique and appropriate voice that challenged reader’s understanding of what it was to be human without anthropomorphising their animal protagonists into children’s book caricatures. As Adrian Tchaikovsky observed, “One of the reasons we don’t like Seagulls or wasps is because they behave like people, lying and bullying.”

Subsequent paper discussions delved deeper into this theme, and indeed the works of three of the authors were examined in detail in four of the papers presented at the conference as presenters addressed the ecological entanglement of human and non-human. Lucy Nield and Elizabeth Ritsema delivered a fascinating two handed presentation focussing on the expectations of literary dog and bear respectively and the disruptive power of language, in Adrian Tchaikovsky’s characters of Rex and Honey from Dogs of War (2017) – a work inspired by H.G.Wells The Island of Dr Moreau (1896).

Dr Valentina Romanzi highlighted how, in Laura Jean Mckay’s impressive debut The Animals in That Country (2020) and Brooke Bolander’s shocking The Only Harmless Thing (2018), the human protagonists are outsiders from their own communities finding kinship and communion with their uplifted animal co-protagonists. These damaged human beings have not left humanity so much as left human society and become anthropogenic strays.

Dr Valentina Romanzi highlighted how, in Laura Jean Mckay’s impressive debut The Animals in That Country (2020) and Brooke Bolander’s shocking The Only Harmless Thing (2018), the human protagonists are outsiders from their own communities finding kinship and communion with their uplifted animal co-protagonists. These damaged human beings have not left humanity so much as left human society and become anthropogenic strays.

Several presenters were engaged in creative research and articulated the challenges of representing the voice of the non-human in their creative pieces. They illustrated this with some haunting extracts from their work such as Rebecca Irvin’s exquisitely poetic piece Horns conjuring images with phrases like “rubbing the heaving from your back” and “eyes full of splinters.” David Tierney highlighted the need to access the whole of an animal’s body to understand and represent animal language, exemplified in both McKay’s text and Ursula Le Guin’s short story The Author of the Acacia Seeds (1982).

This is a theme exemplified in Tchaikovsky’s Children of Time (2015) where the spiders’ communication through physical web transmitted sensation essentially elides the vocal. Nora Castle and Liza Bauer cited Tchaikovsky in their paper on “Reading the Animal” pointing out that the spiders interpreted a captured human’s inability to master even the most basic elements of their web-based communication as clear evidence of the human’s low intelligence. They consequently – somewhat ironically – hypothesised its possible genetically engineered purpose as a low-grade worker. Thus, Tchaikovsky challenges the human assumption that linguistic opacity implies stupidity.

This is a theme exemplified in Tchaikovsky’s Children of Time (2015) where the spiders’ communication through physical web transmitted sensation essentially elides the vocal. Nora Castle and Liza Bauer cited Tchaikovsky in their paper on “Reading the Animal” pointing out that the spiders interpreted a captured human’s inability to master even the most basic elements of their web-based communication as clear evidence of the human’s low intelligence. They consequently – somewhat ironically – hypothesised its possible genetically engineered purpose as a low-grade worker. Thus, Tchaikovsky challenges the human assumption that linguistic opacity implies stupidity.

Even between human languages translation is a process fraught with interpretation, as translators make choices about conveying the text or the meaning. Jonathan Thornton’s examination of Johanna Sinisalo’s The Blood of Angels (2011) – translated by Lola Rogers – looked at the mythic origin of bee stories within the epic Kalevala and Sinisalo positing bees as potential gate keepers and gate openers of portals between parallel worlds. The notion that humans are not the masters of the Earth that they imagine themselves to be was a rich theme in Douglas Adams’ work. However, in moving beyond the familiar mammal perspective of mice and dolphins and looking at the most defamiliarized forms of communication and non-human creature, the papers presented challenged understandings of what it means to communicate and to be human.

Benedict Anderson in Imagined Communities (1983) highlighted the role of formality and standardisation of language in creating communities of individuals who did not all know each other. Johnson’s English dictionary of the 18th century and Grimms ‘Deutches Worterbuch’ a hundred years later were significant steps in defining not just national boundaries but “them” and “us.” Language continues to be a benchmark of regional identity within nations, be it Sicilian in Italy, Catalan in Spain, or Welsh within Great Britain. Speculative fiction, in the rich variety with which it explores notions of non-human language and communication, may help to blur the boundaries between non-human and human and to enhance an understanding of our world as a mosaic of interdependent communities.

CRSF also touched on representations of dystopia and the climate crisis both in the first day’s Keynote from Christy Tidwell and in a number of the papers and panel discussions. Christy talked about how she strives to help her students – mostly with a background in science and engineering and aspirations towards work in construction and infrastructure – to explore alternative future worlds with different kinds of systemic changes. Our default these days appears to be imagining dystopias with a tendency towards fatalism, but Christy used the card games Investing in Futures by Marina Zurkow to encourage students to imagine alternative outcomes.

CRSF also touched on representations of dystopia and the climate crisis both in the first day’s Keynote from Christy Tidwell and in a number of the papers and panel discussions. Christy talked about how she strives to help her students – mostly with a background in science and engineering and aspirations towards work in construction and infrastructure – to explore alternative future worlds with different kinds of systemic changes. Our default these days appears to be imagining dystopias with a tendency towards fatalism, but Christy used the card games Investing in Futures by Marina Zurkow to encourage students to imagine alternative outcomes.

This recognises the challenge that speculative fiction faces in countering the theme of Barthes’ The Death of the Author (1967) and the reality that whatever message or pedagogy they may have intended their work to deliver is undermined by the risk of an audience’s misinterpretation (or more simply the fact that the intended audience won’t pick up those kind of books anyway). Liam Knight (aka @dystopiajunkie) in his paper highlighted how George Orwell in 1984 (1949) and Margaret Atwood in The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) used endo-texts – that is embedded texts or appendices – to contextualise the fictional world they had depicted. These ‘artificial’ appendices are in fact essential to the text and the world that the authors are striving to convey. For example, in Atwood’s appendix – depicting the Offred tapes as the subject of a conference presentation by a patronising and misogynistic academic – the implication is that the ‘post fall of Gilead future’ still has within it the seeds of discrimination and control that drove Gilead. The paper and the text resonated particularly in the context of recent SCOTUS rulings.

Carmen Hildago-Varo, in looking at Jasper Fforde’s Early Riser (2018) examined a dystopia where climate change has caused winters so cold that humans need a drug supported hibernation period to survive it. However, rather than making the context of the dystopia explicit through endo-texts or other means, Carmen noted Fforde uses climate change as a secondary character – apparent to the reader – but one that the novel’s protagonists are oblivious to. This approach of inducing reader dissonance by presenting them with a context that the characters’ accept as normal, offers an alternative method by which future set speculative fiction can highlight current fact. Like reading of American gun laws from an NRA/GoP perspective, or of Brexit from a Tory/ERG viewpoint, the absurd reality of the situation can be seen in sharper relief from the reader’s external perspective. Within Fforde’s novel there is the inevitable corporate malfeasance with the hibernation drug proving unreliable enough to create a cohort of prematurely awakened but intellectually impaired workers to meet the basic labour needs of society.

Carmen Hildago-Varo, in looking at Jasper Fforde’s Early Riser (2018) examined a dystopia where climate change has caused winters so cold that humans need a drug supported hibernation period to survive it. However, rather than making the context of the dystopia explicit through endo-texts or other means, Carmen noted Fforde uses climate change as a secondary character – apparent to the reader – but one that the novel’s protagonists are oblivious to. This approach of inducing reader dissonance by presenting them with a context that the characters’ accept as normal, offers an alternative method by which future set speculative fiction can highlight current fact. Like reading of American gun laws from an NRA/GoP perspective, or of Brexit from a Tory/ERG viewpoint, the absurd reality of the situation can be seen in sharper relief from the reader’s external perspective. Within Fforde’s novel there is the inevitable corporate malfeasance with the hibernation drug proving unreliable enough to create a cohort of prematurely awakened but intellectually impaired workers to meet the basic labour needs of society.

Zoe Wible also touched on matters of corporate misconduct in her presentation on the Jurassic Park franchise and how the latest film in the series – Jurassic World Dominion (2022) – addressed many of the narrative reservations that had existed in earlier films. The film highlighted more explicitly the totality of corporate behaviour in contributing to the unfolding disaster. It also ‘humanised’ the dinosaurs with a named dinosaur and more explicit parental relationships inviting the audience to appreciate parallels between the species. However, as discussed in some of the coffee-time conversation, there is an issue that films which most fully satisfy our critical demands may – in doing so – lose some vital audience engagement from those who want more simple action narratives. It can be hard to shift audience expectations – desires even – that sequels will be more repetitious than evolutionary. The Jurassic Park franchise’s subversion of the “dinosaurs as monsters” trope, mirrors the subversion of gender tropes in Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) and may face similar difficulties in carrying the audience with it.

Zoe Wible also touched on matters of corporate misconduct in her presentation on the Jurassic Park franchise and how the latest film in the series – Jurassic World Dominion (2022) – addressed many of the narrative reservations that had existed in earlier films. The film highlighted more explicitly the totality of corporate behaviour in contributing to the unfolding disaster. It also ‘humanised’ the dinosaurs with a named dinosaur and more explicit parental relationships inviting the audience to appreciate parallels between the species. However, as discussed in some of the coffee-time conversation, there is an issue that films which most fully satisfy our critical demands may – in doing so – lose some vital audience engagement from those who want more simple action narratives. It can be hard to shift audience expectations – desires even – that sequels will be more repetitious than evolutionary. The Jurassic Park franchise’s subversion of the “dinosaurs as monsters” trope, mirrors the subversion of gender tropes in Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) and may face similar difficulties in carrying the audience with it.

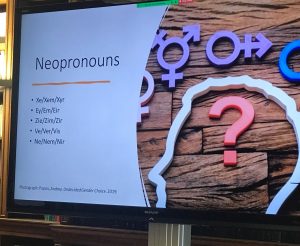

CRSF also touched on issues of gender with Sue Dawes’ discussion of the alternative speculative history in her creative research piece. The piece envisions a group of Victorian women wrecked, with their children, on a pacific island and exploring gendered roles and gender meanings as they struggle for survival. Sue’s research explores how their society migrates to an ungendered or non-binary state and the linguistic challenges of depicting that within in the narrative in a way that was authentic to the period without being intrusive for the reader.

CRSF also touched on issues of gender with Sue Dawes’ discussion of the alternative speculative history in her creative research piece. The piece envisions a group of Victorian women wrecked, with their children, on a pacific island and exploring gendered roles and gender meanings as they struggle for survival. Sue’s research explores how their society migrates to an ungendered or non-binary state and the linguistic challenges of depicting that within in the narrative in a way that was authentic to the period without being intrusive for the reader.

The second day’s roundtable brought four more international authors, Chana Porta, Sue Burke, Vandana Singh and Aliya Whitely, to consider “communicating the other.” Moving beyond depictions of animal-human communication, the authors considered how plants and fungi communicate with each other and in different ways control the humans and animals around them. As Sue Burke pointed out the colour change of a ripening fruit is a clarion call to animals in the vicinity saying “eat me and spread my seeds.”

Dr Jalondra A Davis brought a fascinating conference to a close with the final key-note exploring blackness and merfolk in the Anthropocene. Jalondra’s talk brought out connections between marginalised communities and the elision of blackness in mermaid narratives. Touching on the history of the slave trade and so many of its victims discarded into the ocean from slave ships, Jalondra highlighted how notions of a black mermaid both challenge the heteropatriarchy and offer a means of self-actualisation for marginalised people. In mentioning how black authors are frequently called upon at conferences and round tables to speak as representatives of their race rather than of their writing genre, Jalondra highlighted how black mermaids offered an opportunity for writers like herself to assert an identity for themselves separate from cultural or academic expectations.

In a conference that ran at times two or even three simultaneous panels it was impossible for one correspondent to fully capture or do justice to the totality of an excellent event. The programme and information packs give a glimpse of the research and artistic events covered and there were so many more sessions I would have loved to have gone to. However, I will mention just one more session I did get to. Dr Phoenix Alexander delivered a workshop on writing and selling short speculative fiction stories which was both informative and entertaining. Besides a useful range of resources, Phoenix offered a salutary reminder of the virtue of persistence, with his own considerable current success being born out of a year of submissions before getting his first acceptance, of the third story he had written at the sixth publication he had submitted it to. A brief workshop task invited us to complete a simile “as red as…” in three different ways to show how brainstorming brought a range of ideas to work with. Highlighted suggestions included “As red as a baboon’s arse” from Jonathan and “as red as my power heels” from Lucy, while someone behind me offered “as red as the last sunset.”

After the day closed with a second group attendee’s photograph there was plenty of thought-provoking analysis and inspiring content to reflect on during my journey home. I will be definitely be locking CRSF2023 into my diary next year with the dates confirmed as 29th and 30th June 2023.

A Hive trio of Lucy Nield, Jonathan Thornton & T.O.Munro

Lucy Nield and Pippa the Dog