THE CARBON DIARIES 2015 by Saci Lloyd – THE UNSEEN ACADEMIC

As some of you may know I am currently undertaking a creative writing PhD with the catchy title Navigating the mystery of future geographies in climate change fiction.

This involves reading and watching a lot of climate change fiction (cli-fi) and the Fantasy-Hive have kindly given me space for a (very) occasional series of articles where I can share my thoughts and observations.

It is the fate of works of near-future fiction to eventually be overtaken by the present and – as we pass them by – we may look and smile at the naivety of fiction.

We are 23 years past the period of Space 1999[1] and still no nearer to having a permanent moon base (or a temporary moon).

We are 3 years past the November 2019 setting of Bladerunner[2] with no off or even on-planet replicants to be tested for a lack of empathy (though arguably some contemporary politicians would fail the Voight-Kampff test).

We are seven years past the 2015 of Back to the Future 2[3], with no flying cars or hoverboards, while fax machines are more museum pieces than cutting edge technology for sending employee dismissal notices.

We are seven years past the 2015 of Back to the Future 2[3], with no flying cars or hoverboards, while fax machines are more museum pieces than cutting edge technology for sending employee dismissal notices.

The future can be an unforgiving country for the whims of speculative authors!

So how does Saci Lloyd’s Carbon Diaries 2015[4] stack up? Published in 2008, it was an early example of the cli-fi theme branching into the Young Adult genre. Given the monolithic speed of the publishing industry the story was probably written in 2006, when the era it envisaged lay a decade in the author’s future and seven years in our past.

One immediate feature of Lloyd’s vision of 2015 Britain is that the UK is using Euros as currency and measuring distances in km. Given what has since happened, that vision of European integration feels particularly poignant. However, Lloyd’s future UK still preserves enough precious sovereignty to implement a unilateral green economy measure of carbon rationing.

The stimulus for this truly world leading measure has been an incident simply labelled “the Great Storm.” This catastrophic extreme weather event has finally energised sufficient public opinion and political will to appreciate the need for immediate impactful climate measures. This context feels particularly familiar today with extreme heat waves sweeping the summer, as though we are now standing on a similar precipice to the one Lloyd’s fictional UK faced seven years ago.

credit @willnorman on Twitter

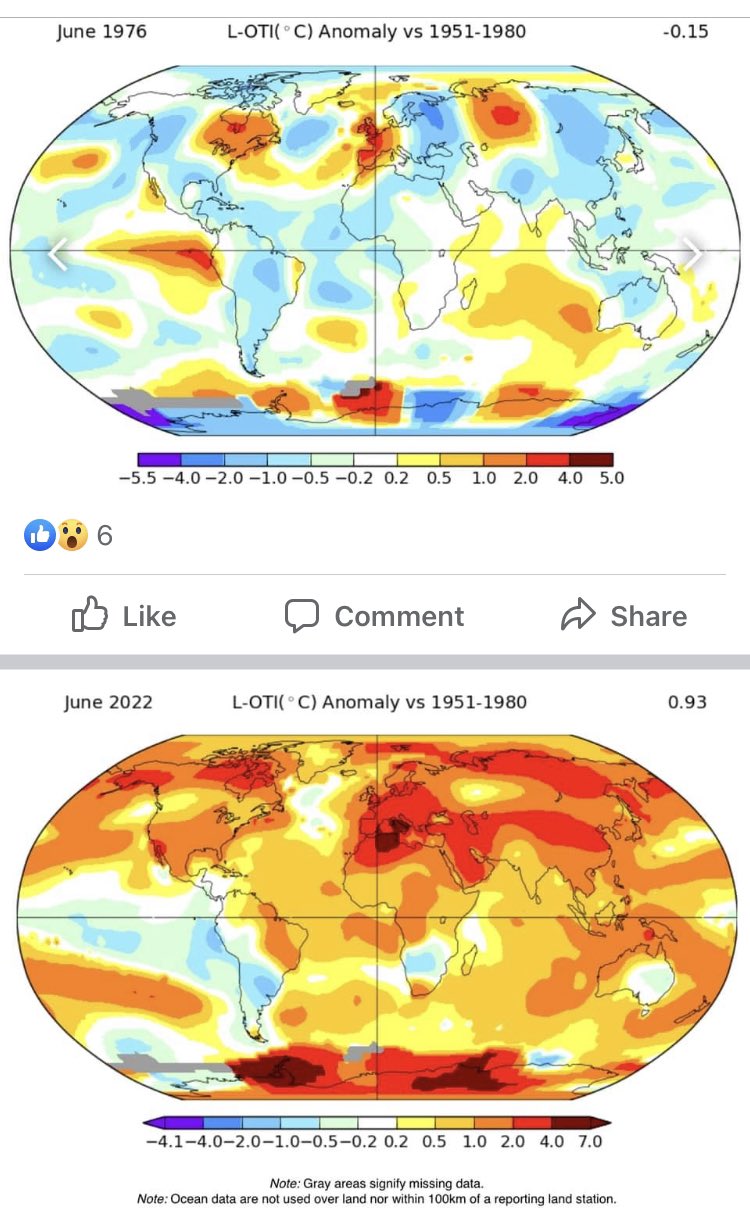

However, as George Marshall highlights in Don’t Even Think About it[5] – human psychology makes us susceptible to the normalisation of extreme weather events. “Even highly visible ones such as Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy, are also part of our accepted way of life – our status quo – in ways that can lead us to accept rather than resist them.” (p. 54). Those who wish – or can be persuaded – to overlook the increasing frequency and severity of these occurrences will take false comfort in past events. For example, there is Ross Clark suggesting that “Older people have been around long enough to remember that we had hurricanes, floods and heatwaves before anyone thought to blame fossil fuel emissions for them, and therefore are less impressed when someone tries to cite a single extreme weather event as evidence of climate change.”[6] We also have people on Social media asserting that 2022 is no different to the sweltering summer of 1976[7] despite ample evidence to the contrary[8]

However, in Lloyd’s future ‘2015’ that single “great storm” has indeed been sufficiently severe to catalyse a policy shift, a determination to achieve a 60% reduction in national carbon emissions within 15 years. An ambition which the frustrated teenager Laura Brown describes as “way over the top” (p. loc 33). The idea that the delay and prevarication over climate change has (or will!) force us into drastic changes and an emergency shift in behaviour is another theme of contemporary relevance. Setting apart the technical challenges in maintaining continuous individual carbon audits, the novum of carbon rationing does make the crisis immediately impactful at an individual and family level, creating an environment in which choices about energy consumption become real, personal and also intrusive. Brown articulates the challenges in a powerful teenage voice.

As Lloyd admitted in an interview (reference) her narrative is inspired by Sue Townsend’s The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole aged 13¾,[9] and Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’ Diary[10]. Another comparator might be the near contemporary Diary of a Chav[11] by Grace Dent (published in 2007 while The Carbon Diaries 2015 would have already been in production) which also combined the teenage perspective of Mole with the more contemporary setting of Jones.

The journal/epistolary approach makes for an interesting refinement of the first-person point of view. The implicit episodic structure allows the author to intersperse a conventional retelling of individual incidents and dialogue between internal monologues of reflection and navel contemplation.

Lloyd’s work has one further innovation with graphics of items stuck in the text – as the diary becomes part annotated archive, part scrapbook. It is to kindle’s credit that the electronic book format allowed me to click on and zoom in on these images, complete with the partially obscuring effect of the Sellotape that stuck them in place – like this souvenir of an ill-fated family bonding holiday that has clashed with Laura’s gigging plans. (p. loc 2214)

Lloyd’s work has one further innovation with graphics of items stuck in the text – as the diary becomes part annotated archive, part scrapbook. It is to kindle’s credit that the electronic book format allowed me to click on and zoom in on these images, complete with the partially obscuring effect of the Sellotape that stuck them in place – like this souvenir of an ill-fated family bonding holiday that has clashed with Laura’s gigging plans. (p. loc 2214)

As Bridget Jones and Adrian Mole illustrated, the diarist rarely emerges reputationally unscathed from their journal entries, given the inevitably heightened aspects of self-absorption and indeed self-deceit that the form defaults to. Lloyd’s Laura Brown is – as Lloyd admitted – intentionally flawed. When asked how she decided on Laura’s flaws, Lloyd replied

“No conscious decision really. Characters tend to have strong ideas about their own development. Laura pretty much appeared fully formed once the first sentence was written. She just wasn’t taking any guidance off anyone, least of all me.”[12]

Laura’s is a ground level view of the climate crisis seen through the eyes and preoccupations of a teenager engrossed in issues of love, school and music as the hot boy next door and the band career she yearns for compete for her attentions. Trexler in Anthropocene Fictions[13], praises how “Instead of holding an artificially unified view, Laura Brown describes the inherent tensions in emissions reduction” (p. loc 4047) and so “Instead of implausible coherence, Carbon Diaries captures the natural ambivalence between politicization and privacy” (p. loc 4052)

Laura Brown is nonetheless an engaging and likeable narrator. The reader cannot help but sympathise as her small nuclear family disintegrates under the pressures of climate change economics and extreme weather events, rapidly shifting her conceptions both of what the future holds and what constitute normal. Lloyd gives her protagonist a lively sardonic style and there were plenty of points where I find myself noting a “nice line.”

For example when Laura’s opportunity to chat with the hot boy next door has been interrupted by the romantically acquisitive top girl in the year.

“I nodded and smiled so much my teeth hurt.” (p. loc 516)

Or later when her boyfriend can’t see her because he is too busy revising with geeks to pursue an apprenticeship in climate amelioration measures.

“Basically it makes me dead sad to have my boyfriend snatched off me by a greenhouse gas.” (p. loc 2532)

Carbon budgets

While the idea of individual carbon budgets does have narrative impact and immediacy, I do find it a potentially problematic fictional motif. By its nature carbon rationing focuses blame and responsibility on the individual and potentially distracts from how corporate behaviour and political inaction have contributed to the crisis. The concept of a carbon footprint is a fossil fuel company construct[14] deliberately developed by BP as a useful element in the strategy of displacing guilt, responsibility and consequences onto individuals and away from corporations. Clark also uses the motif in The Denial[15] as an implicit example of government overreach. The tension between centrally coordinated measures to address the crisis and government’s trespassing on individual choice and freedom is an emotive, even talismanic, concept in the climate denier’s armoury (and also in that of anti-lockdown sceptics) so I feel Cli-fi authors should approach the issue with caution. Lloyd does make a reference to the scheme having to be adjusted to avoid exploitation by the rich,

“At first they set up a free trading system so that if you were rich you could just buy up carbon in cash and live how you wanted- but after the riots last September the Gov backed down.” (p. loc 54)

However, there are complications with black market carbon being sold to the well to do and the low carbon users Laura Brown’s pensioner neighbour Arthur trading their allowances to others. This emphasises the flaws in accountancy driven processes for reducing carbon emissions. While Lloyd admits the imperfections and massive inconvenience in carbon rationing, she also continues to have Laura Brown catalogue climate collapse on such a scale that the rest of Europe (narrowly) votes to accept carbon rationing by the end of the book.

The vote is not a cause for celebration – it is an acceptance of necessary immediate hardship to stave off longer term catastrophe. (One hesitates to suggest how narrowly won votes on contentious issues can turn out to be shockingly divisive.) However, Lloyd’s imagining of carbon rationing unlike Clark’s is clearly perceived as a transitional measure of finite duration. It is intended to last only until the long postponed green energy innovations have finally been implemented and come to fruition. The language of wartime hardship is explicitly referenced along with a notion that the future will thank them for taking this drastic action.

The school headteacher addressing an assembly of returning students finishes

“… by saying our generation would be thanked by all those to come – it was us who finally made the choice to change our lives and save the planet.” (p. loc 2407)

But Laura, unimpressed by the audience’s applause, is – understandably – more of a grouchy conscript than idealistic volunteer in this struggle.

“Er, excuse me, what choice? I ain’t old enough to vote. I feel dead ashamed of myself, but right now I hate rationing. I want my old life back.” (p. loc 2407)

The Carbon Diaries 2015 is a clear warning that the cost of decades of delay will be an emergency stop rather than a slow transition in our fossil fuel use. The irony is that the longer we delay and the more drastic action that is called for the less willing people will be to accept the concomitant reduction in current living standards in exchange for future security. George Marshall argues that “people will be strongly disposed to avoid short-term falls in their living standards and to take their chances on the uncertain but potentially far higher costs that might come in the longer term.” (Marshall, 2014, p. 66). As the increasing crisis risks greater short-term pressures along the lines of those seen in The Carbon Diaries 2015, psychology predisposes us to avoid those short-term falls even more vehemently. One does wonder what event – if any – will be the real “great storm” event that does wake people up to the need to do take immediate impactful action.

Generational Guilt

Lloyd also plays on the nation of intergenerational guilt. While Laura Brown’s elder sister, Kim insists she “wants her life back” (p. loc 14) Laura’s mother Julia is wracked with guilt.

“I’m so sorry, Laura,” Mum stirred her dodgy brown tea. “I know I should be strong, but I feel so responsible for my generation- we’re the ones who’ve messed it up for you.” (p. loc 106)

Of course, not everyone in the older generation feels that much guilt or responsibility for the climate crisis. For example, here we see a Tory party member (who will be voting for the UK’s next PM) saying out loud “I’m at an age where I’m not that bothered about saving the planet.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ePwRtGxYG28 [16]

Again, Lloyd in dealing with the immediate personal family guilt treads close to the emotive notion of a selfish guilty generation of boomers. This sense of guilt is easily weaponised by right wing commentators who bridle at – and encourage others to reject the accusations of guilt, selfishness and privilege. In the eternal victim-villain-rescuer triangle of human conflict, we instinctively reject being cast as the villain and default to seeing ourselves as – if not rescuer – then victim. Posts about white privilege can trigger vociferous social media outbursts, while Black Lives Matter memes could prompt a deluge of All Lives Matter responses. In trying to avoid feeling bad about themselves, people can fall into flawed or bad faith arguments that impede effective co-ordinated action. So, I am wary of narratives that suggest one sector of the population can – or should – accept a totality of guilt.

Which is not say that the generation of Laura Brown’s mother is entirely innocent, or that her regret is in any way insincere. It is just that – while many people do feel a genuine sense of responsibility – others like the Tory member above clearly do not. Narratives of guilt, in threatening to damage their sense of self-worth and identity can be easily dismissed. Ross Clark in The Denial offers a disparaging description of an activist inspired culture of guilt “It had become risky to admit that you missed what had become known as ‘the selfish times’” (Clark, 2020, p. 47)

However, as Dimick noted in ‘From Species to Suspect’[17] there is a continuum of climate guilt. We all have our own parts to play and our own atonements to make. We should not allow any guilt for our own culpability to paralyse us into silence over the greater guilt of corporate malfeasance and political inaction. This is particularly so in an era when the libertarian mantras of “individual empowerment” and “freedoms” become cover for allocations of “blame” and “responsibility.” With climate change, as with covid, the same voices demand we must be given freedom from measures designed to protect us from future harm. Then – while laughing all the way to the bloated bank – the same voices pivot to blame individuals for using those freedoms irresponsibly when disaster happens. It is the right-wing way to throw guilty shade at progressives while ignoring their own far more egregious offences – as the reactions to the recent FBI raid on Mar a Lago seem to demonstrate. It is the progressive way to be more open in accepting responsibility for our own misdeeds. In climate change, as in contemporary politics, we must not allow these tendencies to silence or subdue us; we must reject the “both sides are just as bad” justification for personal doubt and political inactivity.

Corporate Misconduct

To be fair to Lloyd – governments and corporations do come in for some withering criticisms that feel painfully relevant today. The book is full of many more observations that feel like they have been plucked straight from our present news stories rather than the author’s imagination of a decade and a half ago. While, we haven’t reached the point of imposing carbon rations – political incompetence and corporate malfeasance pepper the pages of Laura Brown’s diary just as much they have manifested themselves in the early 2020s news reports.

When a deluge descends

“The sewers can’t cope with all the rain so Thames water pumped 800,000 tons of shit into the river. Good day for the fish.” (p. loc 2882).

In 2022 The Guardian reports “Thames Water dumped raw sewage into rivers 5,028 times in 2021”[18]

Facing the consequences of a climate induced summer drought Brown is also scathing on the London Mayor’s capitulation to the water company and the pivot to urge individual responsibility.

“Patronising pig. Why don’t you think about the thousands of litres pouring away every minute ‘cos you’re too weak to stand up to Thames Water.” (p. loc 1620).

In 2022 Thames Water admits on its own website “At the moment, we leak almost 24% of the water we supply. We know it’s not acceptable to be losing so much precious water”[19]

It is also quite sobering how closely Brown’s fictional diary entries from 2015 converge with 2022 issues around desalination plants, with outraged headlines and twitter conversations.

“I’m going to join the march on Thames Water’s headquarters… we’ve got to force them to do something, at least start building a desalination plant. Y’know, for making clean water out of the sea.” (p. loc 1910).

In 2022 the Daily Mail criticises under-specification and switched off desalination plant.[20]

There is a superficial similarity between the winter power cuts occur in Lloyd’s Carbon Diaries 2015 and Ross Clark’s The Denial but where Clark blames the unreliability of renewables and cowboy builders bodging the home insulation programme, Lloyd’s targets feel very contemporary.

The electricity grid is old and completely messed up cos the private companies have been bleeding it dry since forever. (p. loc 199)

Mentioning the poor planning of UK gas storage as a contributory factor just re-emphasises the quality of research that Lloyd injected into her book as our headlines mirror Brown’s quotes.

Our (gas) storage facilities are tiny. The UK only keeps about eleven days supply for the whole country. Some European countries keep as much as fifty, sixty days. (p. loc 215)

In 2022 inews quotes analysts at HSBC as having said, “The UK’s situation is more precarious than its European neighbours because of its very limited [gas] storage capacity,” [21]

The current cost of living crisis is more political than climate in origin. However, the anticipated winter cold and the solutions Lloyd describes sound terribly familiar. With household thermostats limited to 16oC Brown goes searching for what we would call a warm bank and finds it in Waitrose!

It was so freezing I went shopping to Waitrose with Mum and Dad just to keep my blood moving. (p. loc 154)

In 2022 councils in Yorkshire are planning to provide ‘warm banks’ for the winter [22]

With so many insights of contemporary relevance one would almost ask Lloyd for her lottery prediction. However, I suppose the blunt reality is that the present Lloyd was living in in 2006 has been extrapolated forward in ways that were always eminently predictable for those willing to look and do the research as Lloyd clearly did.

Illuminating the challenges of Cli-fi

George Marshall identifies the difficulty people face in coming to terms with climate change, the hardwiring of our brain means that emotion and immediacy can easily overpower rationality and perspective. He uses Jonathan Haidt’s analogy to help explain how our emotional and rational brains interact like an emotional elephants directed by rational drivers. (Marshall, 2014, p. 49) While it may look like rationality is the one doing the steering, emotion is powerful enough to take charge whenever triggered.

Although, the psychology is slightly more complex than that, it is telling how populists and libertarians often seek to overwhelm rational thinking about issues like climate change, covid, Brexit by appealing to and weaponizing emotions. The inarticulacy of science depicted in Oreskes and Conway’s The Collapse of Western Civilisation: a View from the Future[23] and of the lepidopterist Ovid Byron in Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behaviour[24] both capture this failure on the part of rational reasoned thinking to engage the necessary emotions to prompt action. In Flight Behaviour there is a key moment where – pushed into an interview with a reporter – Byron succumbs to his own passion and delivers a powerful and emotive rebuttal which a second character records and uploads “Posting it on you tube now” (Kingsolver, 2012, p. loc 5510). The recording goes viral under the tagline “This is what science looks like.” (Kingsolver, 2012, p. loc 5571). The scientist can only communicate effectively to the wider audience when he shuffles off science’s rational reticence and obscure but (ironically) precise use of the word ‘uncertainty.’ It is when he surrenders to emotion that he delivers the kind of passionate certainty that wins more arguments than wagon loads of evidence.

Marshall talks about how “...everyone, experts and non-experts alike, converts climate change into stories that embody their own values, assumptions and prejudices.” (Marshall, 2014, p. 3). There is a reason why fables and stories open avenues for communication, by engaging us emotionally in a process of rational understanding. It is through the stories we tell that we recognise and address the many psychological barriers to engaging with climate change and what is cli-fi if not “telling stories.” However, the emotional elephant is a difficult creature to steer at the best of times let alone through the medium of fiction. Readers are prone to garnering unintended messages and finding interpretations which sanction the status quo and excuse passivity. Grim distant dystopias prompt despair that action is now hopeless or relief that it is only a story that won’t happen. Visions of heroic bands inventing technology to save us can inspire the reader to relax and expect science to solve the problem before they or theirs are directly affected. This almost religious faith in technology reminds me of a joke I will save for a foot note.[1]

It is not the fault of humans that we are hardwired to be emotionally driven tribal beings – though we should always strive individually to overcome those biases, to be better than that. However, we should not ignore the role that corporate misinformation and political misdirection continue to play in exacerbating the crisis and impeding responsible action. Those in the media, politics and the corporate world who weaponise that inherent human susceptibility to emotive messaging, who use that evolutionary vulnerability to drive through climate inactivism agendas which enhance their own influence and wealth, should be held criminally at fault for the unfolding crisis.

Lloyd’s tale ends with another extreme weather event as the iconic Thames barrier is overtopped by a storm surge. Unlike the relatively minor inconvenience of the mis-forecast storm in Ross Clark’s The Denial, Lloyd gives us a disaster of Hurricane Katrina proportions. However, it is not one without hope as neighbours who Laura Brown knows only by Brown in-family sobriquets such as “loud dad” and “mousy woman” rally to make the most of a difficult situation. It is in that vision of a community awakening and collaboration to fight the crisis that Lloyd offers us most hope.

Conclusion

Lloyd’s The Carbon Diaries 2015 remains a powerful and well written example of cli-fi that, like a good whisky, has been improved with age. Unlike other future-set works its messaging and imagery has become strikingly more relevant and resonant. In 2008 the novel’s vision felt like a warning – a call to take action in the present time of publication to avoid the disturbing future exigencies of the novel. Now, with climate records being broken in ways that echo passages in the book, The Carbon Diaries 2015 feels more like a prescription – and an unpalatable one at that – for our present.

However, it still doesn’t have to be like that if we can generate the political will to take necessary action. Even as the Tory leadership candidates race to convince their tiny selectorate of members that they will reverse commitments to solar farms and wind turbines even while fuel bills rocket – the truth is that energy from off-shore wind is four times cheaper than gas.[25] The switch to renewables has a payback time of six years.[26] The amount the US spends on climate change measures is a tiny fraction of its defence budgets – suggesting plenty of financial headroom to move faster.[27] All it needs is a popular rejection of fossil fuels, their corporations, their lobbyists, their paid up political shills and their disingenuous climate inactivism/denialism.

There is still time for Lloyd’s The Carbon Diaries 2015 to be a warning, rather than a forecast, provided we are willing to act on it and Keep the fossil fuels in the ground.

[1] Joke(?): A godly man trapped on the roof of his house in a flood, rejects rescue in turn from a kayak, a motorboat and a helicopter insisting that “God will save me.” However, to his surprise the flood waters rise and drown him. So, on arrival in Heaven, he asks God “Why didn’t you save me?” and God replies, in exasperation, “Save you? I sent you a kayak, a motorboat and a helicopter!”

If I could translate this into a climate deniers’ and scientists’ context, the climate deniers repeatedly reject calls to “keep the fossil fuels in the ground” because “Science will save us.” In a few short years, however, climate change overwhelms the world stranding a handful of survivors in some post-extinction event afterlife. And the climate deniers turn to the scientists and ask, “Why didn’t you save us?” And the scientists say, “We told you to keep the fossil fuels in the ground.”

End notes

[1] (Anderson, 1975)

[2] (Scott, 1982)

[3] (Zemeckis, 1989)

[4] (Lloyd, The Carbon Diaries 2015, 2008)

[5] (Marshall, 2014)

[6] (Clark, Are old white men really to blame for climate change denial?, 2017)

[7] (TheFreds, 2022)

[8] Will Norman shared this graph on twitter (Norman, 2022) having constructed it from Nasa data (NASA, 2022) (available on this website https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/maps/ ) Also, as Professor Hannah Cloke, climate scientist at the University of Reading, noted in a comment for the website IFL Science, “1976 was indeed a heatwave and we have had heatwaves before, but the point is they’re happening more often and they’re becoming more intense.” (Dunhill, 2022)

[9] (Townsend, 1982)

[10] (Fielding, 1996)

[11] (Dent, 2007)

[12] (Lloyd, Through the Looking Glass Book Reviews: An Interview with Saci Lloyd, the author of the Carbon Diary books, 2010)

[13] (Trexler, 2015)

[14] The notion of Carbon Footprint was devised by PR professionals employed by the fossil fuel giant British Petroleum specifically to shift the focus from corporate fossil fuel use to accounting for individual contributions for the fossil fuel related climate change. (Bergan, 2021)

[15] (Clark, The Denial, 2020)

[16] (Campbell, 2022)

[17] (Dimick, 2018)

[18] (Laville, 2022)

[19] (Thameswater, 2022)

[20] (Haigh, 2022)

[21] The report shows that the UK actually shut down gas storage to a lower level even than Lloyd anticipated (Cuff, 2022)

[22] (Armstrong, 2022)

[23] (Oreskes & Conway, 2014)

[24] (Kingsolver, 2012)

[25] As the Carbonbrief reported in July 2022 “Analysis: Record-low price for UK offshore wind is four times cheaper than gas” (Evans, 2022)

[26] As The Hill reported, “We found that the overall upfront cost to replace all energy in the 145 countries which emit 99.7% of world CO2 is about $62 trillion. “However, due to $11 trillion annual energy cost savings, the payback time for the new system is less than 6 years.” (Jacobson, 2022)

[27]Pemberton and Powell in their 2014 report for the Policy Institute “Combat vs Climate: The military and climate security budgets compared” looked at US spending and compared it to China’s (Pemberton & Powell, 2014) At that time the US was spending 24 times as much on defence as on climate security measures. While this was an improving ratio the improvement was only partly deliberate (ramping up climate spending) and partly incidental (reducing defence spending due to withdrawing from Iraq). The ratio also compared poorly with China which spent 3 times less on defence and 8 times more on climate security bringing climate security and defence spending almost level. Incidentally this difference was picked up by Oreskes and Conway in The Collapse of Western Civilisation, A View From The Future (Oreskes & Conway, 2014). They toyed with the notion that China – unburdened by the need to defer to the billionaire and corporate donors who buy political power and influence (still less the pesky and/or manipulated electorate) – would be more able to make the agile rational responses necessary to better survive the climate crisis. Ironically, in the US it is the military – whose job it is to assess and respond to risks – who have brought the most rational approach to engaging with climate change and taking precautionary measures. As Marshall put it “The most rational and considered response to the uncertainties of climate change can be found among military strategists.” (Marshall, 2014, p. 75)

References

Anderson, G. (Director). (1975). Space 1999 [Motion Picture].

Armstrong, J. (2022, August 4). ‘Warm banks’ could be opened for people struggling to heat their homes this winter. Retrieved from examinerlive.co.uk: https://www.examinerlive.co.uk/news/cost-of-living/warm-banks-could-opened-people-24669843

Bergan, B. (2021, August 27). ‘Carbon Footprint’ Was Coined by Big Oil to Blame You for Climate Change. Retrieved from interestingengineering.com: https://interestingengineering.com/culture/carbon-footprint-coined-by-big-oil-to-blame-you-for-climate-change

Campbell, E. (2022, August 5). Meet the ‘normal’ Tories choosing the next prime minister. Retrieved from Youtube.com: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ePwRtGxYG28

Clark, R. (2017, September 22). Are old white men really to blame for climate change denial? The Spectator. Retrieved from https://archive.ph/kbq33#selection-525.119-525.402

Clark, R. (2020). The Denial. London: Lume Books.

Cuff, M. (2022, 2 3). Energy bills rise: Getting rid of gas storage facilities has left the UK exposed to shortages and price hikes. Retrieved from inews.co.uk: https://inews.co.uk/news/uk-gas-storage-facilities-shortages-energy-price-rises-rough-1441830

Dent, G. (2007). Diary of a Chav. London: Hodder Children’s Books.

Dimick, S. (2018). ‘From Species to Suspect: Climate Crime in Antti Tuomainen’s The Healer’. Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal, 51(3), 19-35.

Dunhill, J. (2022, Juky 19). Was 1976 Really As Hot As 2022, Or Is It Just Climate Denialism? Retrieved from IFL Science: https://www.iflscience.com/was-1976-really-as-hot-as-2022-or-is-it-just-climate-denialism-64505

Evans, S. (2022, July 8). Analysis: Record-low price for UK offshore wind is four times cheaper than gas. Retrieved from carbonbrief.org: https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-record-low-price-for-uk-offshore-wind-is-four-times-cheaper-than-gas/

Fielding, H. (1996). Bridget Jones’ Diary. London: Picador.

Haigh, E. (2022, August 4). Thames Water’s £250million desalination plant is turned OFF even though it is supposed to supply drinking water to 400,000 London homes every day during droughts. Retrieved from dailymail.co.uk: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-11080931/Thames-Waters-250million-desalination-plant-designed-supply-water-400-000-homes-turned-OFF.html

Jacobson, M. (2022, June 28). No miracle tech needed: How to switch to renewables now and lower costs doing it. Retrieved from thehill.com: https://thehill.com/opinion/energy-environment/3539703-no-miracle-tech-needed-how-to-switch-to-renewables-now-and-lower-costs-doing-it/

Kingsolver, B. (2012). Flight Behaviour. New York: HarperCollins.

Laville, S. (2022, April 20). Thames Water dumped raw sewage into rivers 5,028 times in 2021. Retrieved from theguardian.com: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/apr/20/thames-water-raw-sewage-rivers-2021

Lloyd, S. (2008). The Carbon Diaries 2015. London: Hatchette Children’s Books.

Lloyd, S. (2010, April 27). Through the Looking Glass Book Reviews: An Interview with Saci Lloyd, the author of the Carbon Diary books. (M. Jansen-Gruber, Interviewer) Ashland, Oregon, USA: Through the Looking Glass, An exploration of Children;s Literature. Retrieved from (lookingglassreview.blogspot.com

Marshall, G. (2014). Don’t Even Think About it: Why our brains are wired to ignore climate change. Bloomsbury: London.

NASA. (2022, August 10). GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (v4). Retrieved from National Aeronautics and Space Administration: https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/maps/

Norman, W. (2022, July 17). @willnorman. Retrieved from Twitter: https://twitter.com/willnorman/status/1548547271725240323

Oreskes, M., & Conway, E. M. (2014). The Collapse of Western Civilisation: A View from the Future. New York: Columbia University Press.

Pemberton, M., & Powell, E. (2014). Combat vs Climate: The Military and Climate Security Budgets Compared. Washington: Institute for Policy Studies.

Scott, R. (Director). (1982). Bladerunner [Motion Picture].

Thameswater. (2022). Our Leakage Performance. Retrieved August 10, 2022, from Thameswater.co.uk: https://www.thameswater.co.uk/about-us/performance/leakage-performance

TheFreds. (2022, July 17). @TheFreds. Retrieved from twitter: https://twitter.com/TheFreds/status/1548687013955731456

Townsend, S. (1982). The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole aged 13 3/4 . London: Methuen.

Trexler, A. (2015). Anthropocene Fictions: The Novel in a Time of Climate Change. Charlottes Ville and London: University of Virgina Press.

Zemeckis, R. (Director). (1989). Back to the Future II [Motion Picture].