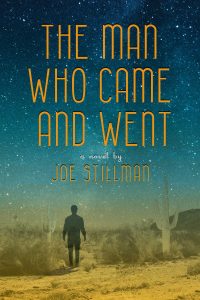

THE MAN WHO CAME AND WENT by Joe Stillman (BOOK REVIEW)

‘Being seen was more beautiful than anything I had ever known’

Instagram: @joethestillman Twitter: @JoeStillman1

Huge THANK YOU to Saichek Publicity for my review copy

Joe Stillman’s writing credits include “Shrek,” “Shrek 2,” “King of the Hill,” “The Adventures of Pete and Pete,” “Beavis And Butthead,” “Planet 51,” and “Gulliver’s Travels,” among others. For “Shrek” he was nominated for an Oscar and won a BAFTA award. For “King of the Hill” he was nominated for two Emmys.

His first writing job in college was the movie trailer for Frank Zappa’s, “Baby Snakes.” As a copywriter, Joe worked on over 200 movie campaigns. Eventually that led to TV promos and then “The Adventures of Pete and Pete” for Nickelodeon, on which Joe was head writer. After writing about 20 episodes of “Beavis And Butthead”, Joe pitched “Beavis And Butthead Do America” and wrote it with Mike Judge. It was his first produced feature and, more importantly, provided a tax write-off for the drive from New York to Los Angeles.

His first novel, “The Man Who Came And Went” was the result of a 30 year journey that included failures, near-misses, and approximately 9000 pounds of self-doubt. If you should decide to purchase a copy, the amortized income of Joe’s effort would come to about 9 cents per year, for which he would be very grateful.

From one of the writers of Shrek, comes a fantastically philosophical novel The Man Who Came and Went. Joe Stillman explores philosophical concepts of reincarnation (rather than the more widely known religious concepts of reincarnation) whilst bluntly, and hilariously, looking at mundane and banal aspects of day-to-day life. Stillman unpicks the seams of a mediocre existence, cutting into the flesh of what one might dub an ordinary or maybe even uninspired life, with little or no aspiration and expectation. His characters have managed to drag themselves through their prosaic existence, heaved themselves onto Stillman’s page where they languish until he is ready to wake them up. A story that begins in a fizzled out, ‘coffin-sized’ town called ‘Hadley,’ which could be one of any typical small, American, desert-type towns, Stillman build’s a narrative with delicate nuance and a intricacy that goes beyond what one might expect from the creator of the lovable sassy green ogre we grew up with (or at least, I grew up with).

From one of the writers of Shrek, comes a fantastically philosophical novel The Man Who Came and Went. Joe Stillman explores philosophical concepts of reincarnation (rather than the more widely known religious concepts of reincarnation) whilst bluntly, and hilariously, looking at mundane and banal aspects of day-to-day life. Stillman unpicks the seams of a mediocre existence, cutting into the flesh of what one might dub an ordinary or maybe even uninspired life, with little or no aspiration and expectation. His characters have managed to drag themselves through their prosaic existence, heaved themselves onto Stillman’s page where they languish until he is ready to wake them up. A story that begins in a fizzled out, ‘coffin-sized’ town called ‘Hadley,’ which could be one of any typical small, American, desert-type towns, Stillman build’s a narrative with delicate nuance and a intricacy that goes beyond what one might expect from the creator of the lovable sassy green ogre we grew up with (or at least, I grew up with).

“Eggs are change.

“Change is everything.

“Where we come from, everything is.

“Here, on a planet, everything changes into something else.

“you never really know what will happen before an egg hits the grill.”

Belutha Mariah, our story-teller, is Fifteen-years old. Stillman has written her to be fairly likeable, dripping with teenage angst and frustration, with a faint whiff of something slightly annoying, something that one might notice of a younger somewhat irritating cousin or sibling. Belutha is obsessed with her mother Maybell. Obsessed with her sexual history, how she dresses and shoves her (what Belutha describes as) large assets into teeny tiny tops to get the attention of men, and she is obsessed with preventing Maybell from getting pregnant again. They live in a trailer that sounds like it is held together with duct tape, along with Belutha’s two siblings (different dads of course) and she is always ready with a shot gun on the porch ready to scare off the next potential sperm doner. Nicknamed as such because the men in Maybell’s life never seem to keep her bed warm for very long.

‘A dog will eventually give you love or loyalty. Maybe fetch a stick. Every guy Maybell brought home would take his sex and go’

Belutha is angry with her lot in life, she never wanted to live this way and feel’s trapped by Maybell and her vast variety of sexual decisions (when I say she is obsessed with Maybell, I mean it). Although she feels trapped, she also seems isolated and states repeatedly that she does not belong, existing only as an insipid wall-flower, never able to escape from her precarious upbringing and boring life.

‘In school, and I guess in life, there are two kinds of people. Those who belong with other people. And those who don’t’

For the entire novel, Belutha desperately avoids men and sex. She makes some hilariously poignant statements about some of the men she has met and their attitudes towards sex and each other, adding the humour to Stillman’s novel that makes it such a relatable and enjoying piece:

‘The problem with men isn’t their natural stupidity. It’s the added stupidity they voluntarily impose on themselves to get along with other men. It starts when they’re boys. I know, I’ve seen It happen. They believe they need to act dumb in order to get along with the other boys. Through their lives, they learn to cut off their own intelligence, the way a doctor cuts off a baby’s foreskin. And like foreskin, that intelligence doesn’t grow back.’

Maybell runs the town’s only diner, which is described as a typical greasy spoon, with bar stools, dirty cutlery and a crappy breakfast cook. One day, a mysterious drifter called Bill comes to the diner. After the crappy cook walks out, he begins cooking eggs for the locals, and weirdly he get’s every order correct – without asking anyone. Bill knows what breakfast the customers want before anyone even orders, and so he begins to work the grill.

Maybell runs the town’s only diner, which is described as a typical greasy spoon, with bar stools, dirty cutlery and a crappy breakfast cook. One day, a mysterious drifter called Bill comes to the diner. After the crappy cook walks out, he begins cooking eggs for the locals, and weirdly he get’s every order correct – without asking anyone. Bill knows what breakfast the customers want before anyone even orders, and so he begins to work the grill.

The aesthetic of this novel is overpowering to say the least. For anyone who might have happened upon TV show’s like ‘My Name is Earl,’ ‘True Blood,’ or ‘It’s Always Sunny,’ will know the rustic, trailer-park, southern aesthetic I mean. There is something aggressive about these types of settings and topography, but overpoweringly familiar and comforting, with a sense of community and belonging that you rarely find in your own home-towns. Whilst everyone knows each other, everyone knows each other’s business and drama. Leading to many yelling matches and unnecessary shenanigans.

“What the hell is this?” He held up my book: Lesbian Thought. […] “You’re too young to be a lesbo!”

I’ve noticed that some men fear lesbianism the way doctors fear Ebola, as if one case could lead to a global outbreak.

“I’m studying to be one so’s I won’t ever be sexually dependent on men scum like you.”

But I love it. I feed off these types of narratives. There is nothing too phantasmagorical. No amorphous or slimy alien blobs of ominous origins. Just people, dealing with people problems. From trying to run a crappy diner, to getting boys to pay attention to you, to going to visit a fry cook who can read minds because you are trying to figure out what happens after you die…. You know, normal people problems.

“I am this body, this body is me”

Stillman handles existential dread by making it a bodily issue, which is a pretty interesting way to think about things. Rather than a build up fear concerning the mind or the soul, the focus is on the body. Moving away from our internal psychic systems into something more physical as what defines who you currently are, but not who you have always been, is genius.

From Shrek to The Man Who Came and Went. Stillman’s first novel is something unexpected, powerful and leaves you weirdly wanting to go and get a fry up. I look forward to what Stillman will do next.

“As a boy, he had hundred of them lining the walls of his room. Each book contained world the Martin preferred to his own. It’s not that he had a particularly bad childhood. In fact, he remembered almost nothing of it. But, like Sonny Boy, he found solace in escape.”

The Man Who Came And Went is available now from:

Amazon.com | Barnes and Noble | Booksamillion | Bookshop.org | Indie Bound