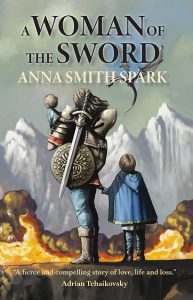

A WOMAN OF THE SWORD by Anna Smith Spark (Book Review)

A Woman of the Sword is set on the many-nationed continent of Irlast which featured in Smith Spark’s debut Empires of Dust trilogy. That trilogy followed the incomparable Marith as he waged war on the world. This sequel is set, I would guess 20 to 30 years after that trilogy closed. Marith’s successors, like Alexander the Great’s generals have been carving up his legacy each one seeking to establish their supremacy and take on the mantle of his successor.

A Woman of the Sword’s eponymous protagonist, Lidae was swept into that maelstrom of warfare when her town was sacked, her family killed and her career options shrunk to a binary choice of victim or soldier. She chose the latter, was successful at it, married a fellow soldier and they both survived long enough for peace to break out allowing their retirement to start a family on a farm in a little coastal village.

However, although the story chronology starts at Chapter Two with Lidae at this happy ending point, Chapter One is something of a framing story foreshadowing the fact that Lidae will be returning to the martial path and find herself in another bloody and desperate battle.

However, although the story chronology starts at Chapter Two with Lidae at this happy ending point, Chapter One is something of a framing story foreshadowing the fact that Lidae will be returning to the martial path and find herself in another bloody and desperate battle.

While the setting and writing will be comfortably familiar to those who enjoyed Empires of Dust, A Woman of the Sword deviates in some significant ways from its predecessor trilogy.

Empires of Dust had several point of view characters; Marith – the world king, Thalia – the high priestess of Living and Dying, Orhan – the political wheeler and dealer of Orlost, amongst many others. A Woman of the Sword follows just Lidae, keeping us in close third person contact with her thoughts, feelings and fears.

Empires of Dust took three books to take complete the story arcs of its multiple characters, A Woman of the Sword is that rarity in fantasy fiction – a stand-alone novel. Don’t get me wrong. I like trilogies, I’ve read quite a few (even written one!). But there is a particular and rare pleasure in starting a book knowing that it will lead you through a complete character arc, leaving you maybe to muse on how the characters’ lives progress after the last page, but content that the author has no more to tell you and no sequels to burden your tottering TBR pile.

Empires of Dust showed us the leaders – the movers and shakers of kingdoms and worlds, the ones who decided where, why and with whom the battles would be fought. A Woman of the Sword puts us in the mind of an ordinary soldier and her fellow squad members, some days marching North, some days marching South, waiting to be told which direction to charge in and who to fight, and being frequently surprised by who turns out to be today’s enemy.

This approach nicely scratches the narrative itch I have been feeling these days, a dissatisfaction with the way fantasy stories often focus on the rich and powerful – the war makers, and world shakers. For example, beautifully gentle as The Goblin Emperor is, the protagonist is still literally an emperor with access to wealth power and influence beyond the reach of normal people. Our stories like our view of history have seemed tilted towards studies of monarchs, and generals, ministers and champions.

Perhaps it is the current political climate and cost of living crisis that is driving my hunger for stories that look at ordinary people and the triumphs and disasters within ordinary lives, rather than submitting to a media driven obsession with the rich and powerful as though the billionaires, the popstars and the politicians were the pinnacle of human existence, while the rest of us are reduced to paupers and gawpers, noses pressed against the plate glass windows of the restaurant of privilege. Such perspectives ignore the fact that an ordinary life is still shot through with rich veins of tragedy and drama.

So it is refreshing to find Smith Spark writing about just such folk, the foot-soldiers, the refugees, the camp followers. Theirs not to reason why – theirs just to try not to die! We follow Lidae, the neighbours of her brief civilian sojourn, and squad mates of her army days. Their vague understanding of wider politics and diplomacy enhances the gritty descriptions of camp life and the compelling nature of Lidae’s multiple conflicts between career and motherhood, between trust and betrayal, between her eldest and her youngest child.

And it is not just in her personal influence on world events that Lidae deviates from the tropish starring roles with protagonists being some form of ‘chosen one’. At DublinCon in 2019 I attended one panel which asked a question to the effect of “Where are the crones?” The panel mused about speculative fiction’s seeming preoccupation with either adolescent/young adult – or ancient wizened hags as female protagonists. One panellist (it may have been Anna Stephens?) expressed a desire to see a protagonist of mature but not decrepit years, one with a bit of life experience and the stretchmarks to prove it – in short to see the mother rather than the maiden or the crone.

In Lidae, Anna Smith Spark has created just such a protagonist, skilled but not overpowered, fiercely protective of her two sons, and inducted into the soldiering life as a matter of necessity rather than choice. Old wounds trouble her and greying hair earns some double takes from friends and foes who do not immediately realise her talent for battle. She is a poet of the sword and within the circle swept by its blade she has the skill to take on anyone (but just not everyone at once!).

Smith Spark’s writing style veers more to the literary end of the prose spectrum, as is apparent in some long paragraphs and passages that follow a stream of consciousness in Lidae’s thoughts. There is an authenticity to the dialogue, capturing that blend of confidence and hesitancy that peppers real everyday interactions. Smith-Spark conjures scene and setting in a vivid reality, such that one of my marginal notes to myself was simply “Funny how the writing about food makes me hungry!!” and later another passage “Making me so hungry!!”

Among the ‘nice lines’ that I had marked is this early description of a battlefield death

“His teeth gnaw the black earth the light hisses from his body cold silence claims him.”

And this description of a field in flower

“The wheat in the field was palest jewel scattered green-silver. Purple saxifrage in spreading pools of colour, white anemones and white poppies and white laceflower; elderflower frothed like seafoam, sweet-calm-scented with a musk to it like a child’s skin.”

Gritty descriptions of battle evoke the reality of ancient and medieval battles, the shield walls crashing together, each soldier’s thoughts and ambitions shrunk to the next minute, the next step, the next adversary. It is the battle vision of films like 1917 or All Quiet on the Western Front rendered as text.

Although offering a more literary take on the fantasy genre, Smith Spark’s writing always remains accessible and absorbing with eye-catching lines and compelling characters. (It is worth remembering that literary fiction is no more or less a genre than speculative fiction, and that genre boundaries are meant to be blurred and crossed for any attempt to categorise authors and books is as doomed as trying to herd cats.)

The plot covers a period of a little over a decade as Lidae grows older in the service of war and her two sons grow to manhood and forge their own careers. While Lidae’s foot soldier view means she is never quite sure of what is going on, the veteran soldier Clews – a survivor from the Empires of Dust – drifts in and out of Lidae’s story, better informed and so able to offer cryptic guidance and warnings.

While Lidae is at times soldier, refugee, camp-follower and then soldier again as events sweep her, her family and her fellow refugees far from their home by the sea, A Woman of the Sword set many associations sparking in my mind.

It set me thinking of: Alexander the Great’s soldiers cross-crossing Asia minor in search of battle, wealth and the faint chance of a wealthy and peaceful retirement: or Shakespeare’s Richard III – a warrior king bemoaning the weak piping time of peace that his seen his bruised arms hung up for monuments; or the bard’s Mark Antony, cradling Ceasar’s corpse and promising that a curse shall light upon the limbs of men, fierce civil strife shall cumber all the parts of Italy, blood and destruction shall be so in use, and dreadful objects so familiar, that mothers shall but smile when they behold their infants quartered by the hand of war, all pity choked with custom of fell deed; or even Buffy Sainte-Marie’s anti-war ballad The Universal Soldier bemoaning the foot-soldiers in every age who gift the kings and generals power with their bodies and their blood

And he’s fighting for Canada, he’s fighting for FranceHe’s fighting for the USAAnd he’s fighting for the Russians and he’s fighting for JapanAnd he thinks we’ll put an end to war this way

Universal Soldier – by Buffy Sainte-Marie

Ultimately Smith Spark’s depicts a cycle of warfare in Irlast with the paradox of would-be kings each striving to prove themselves fit to maintain the peace by being the one to wage the most complete and dominant war, to be – if you like – the Alpha king.

His men spread out across the world in blood and ruins to build a world of peace for him.

But as Lidae struggles with motherhood I was also reminded of the Olivia Colman and Jessie Buckley playing the older and younger Leda Caruso in the film The Lost Daughter. Buckley in particular caught the kind of paradox of motherhood that seems to afflict Lidae, the contest between love and hate, between guilt and duty as shown in these two lines.

Always the wretched children snivelling at her feet stopping her, stopping her doing anything.

But later

And a tiny voice in her heart, even now, triumphantly within her: you do love them, you see? You say what a good mother says, you do love them.

A Woman of the Sword is a different but very satisfying fantasy reading experience with, in Lidae, a captivating protagonist at times fierce and proud, conflicted and tormented, but never less than compelling.

A Woman of the Sword is due for release 4th April from Luna Press Publishing. You can pre-order your copy HERE

[…] up the soldier’s life by joining the invading army through a feat of trickery, a necessity, as a Fantasy Hive article points out, given her alternatives are likely death or enslavement. The deprivation of one’s […]

[…] up the soldier’s life by joining the invading army through a feat of trickery, a necessity, as a Fantasy Hive article points out, given her alternatives are likely death or enslavement. The deprivation of one’s […]

Buffy Sainte-Marie’s ballad brought to my mind A.E.Housman’s Grenadier, such fury and compassion commingled.