Interview with Anna Smith Spark (A WOMAN OF THE SWORD)

Anna Smith Spark is the author of the critically acclaimed grimdark epic fantasy trilogy Empires of Dust described by The Sunday Times as ‘Game of Literary Thrones … the next generation hit fantasy fiction.’

Anna lives in London, UK. She loves grimdark and epic fantasy and historical military fiction. Anna has a BA in Classics, an MA in history and a PhD in English Literature. She has previously been published in the Fortean Times and the poetry website www.greatworks.org.uk. Previous jobs include petty bureaucrat, English teacher and fetish model.

Anna’s favourite authors and key influences are R. Scott Bakker, Steve Erikson, M. John Harrison, Ursula Le Guin, Mary Stewart and Mary Renault. She spent several years as an obsessive D&D player. She can often be spotted at sff conventions wearing very unusual shoes.

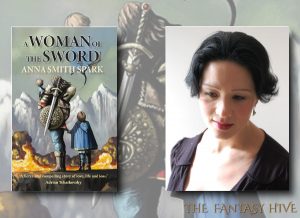

T.O.Munro (TOM) Hi Anna, and thanks for coming back to the Hive for a second interview. A lot has happened in fantasy fiction, the world at large and in your writing since you were talking to Mike Everest Evans back in September 2018, so there’s lots to catch up on. We’ll start by looking at your upcoming release of A Woman of the Sword with Luna Press Publishing – timed for an Eastercon Launch on April 4th and with an online launch on 27th March. There’s also a video of you reading the first chapter for those impatient for the launch!

Although A Woman of the Sword is a standalone novel, it is set in the same world as your previous Empires of Dust trilogy. While there is no need to have read that trilogy in order to enjoy or understand A Woman of the Sword I did notice some returning names and characters.

Can you tell us a little bit more about how this work fits in with and draws on the previous trilogy?

Anna Smith Spark (AS) It’s sort of set in the same world but not … You can certainly read it as a standalone without any knowledge of my previously books. A Woman of the Sword is taking the same backdrop, this huge destructive war and its aftermath, and telling a totally different story within it. So Empires of Dust is about kings, lords, people of power, people playing the game of thrones. A Woman of the Sword is about the people whose lives are consumed in that game. They don’t understand what’s happening, don’t have insight into the intrigue, the backstory to a battle, a betrayal, a surrender – they just have to live with the consequences.

In Empires of Dust we saw Marith win or lose a battle, decide to sack or spare a city, and the focus was on his thought processes, the consequences of it all for him and those around him. As I was writing the last volume, The House of Sacrifice, I got more and more caught up thinking about the lives of the footsoldiers in an epic fantasy war. They go into battle and are defeated because … they don’t know why. They march south rather than west, betray an ally or are betrayed, and they have no idea what the reasons are. Or in real history, the Wars of the Roses say – your commander defects, you’re suddenly fighting troops you thought were allies, or your commander decides to sacrifice your squad for the greater victory, but you don’t know that. Or the non-combatants, the farmers, the small shopkeepers – an army crosses a river at one ford or another, choses one city over another to march towards, sacks or spares that city, you don’t know why and will never know but your life is changed forever, you literally live or die because someone somewhere chose a route on a map. I wanted to tell a story about those people, the real people just living in this world not the big lead players. The nameless extras in the background of Empires of Dust, look at the impact of war and chaos on them.

Chronologically, the book sits shortly after Empires of Dust finishes. Some of the events and characters are referenced but ‘wrongly’ – they’ve become confused, turned into stories by the people living through them. The way even very recent events are forgotten, changed, muddled up also interests me. In a world with limited literacy and no mass media, the past is very quickly distorted – especially as political allegiances shift over time. I wanted to reframe a few things from Empires of Dust in a way that seemed plausible, change a few details to show a different version through someone else’s eyes.

But I swear on my name and my writing hand and the life of my firstborn book, you don’t need to have read anything else I written to read A Woman of the Sword. It’s not like picking up book four of Malazan without having read one to three and you’re totally lost as to what’s going on or why- wait …. thinks about this …. let’s rephrase …. it’s not like picking up a book four where it’s only clear what’s going on if you’ve read books one to three … what I’m trying to say is it’s not book four of Empires of Dust it’s something very different and standalone just with echoes. If you haven’t read my other books you can read this fine.

TOM Empires of Dust is a successful and innovative trilogy with a broad ranging narrative in terms of setting, style and varied points of view. I found it resonated with the history and conquests of Alexander the great.

TOM Empires of Dust is a successful and innovative trilogy with a broad ranging narrative in terms of setting, style and varied points of view. I found it resonated with the history and conquests of Alexander the great.

As you moved into this book what in your approach and intentions stayed the same, and what were you trying to do differently?

AS I wanted to write something more personal and rooted in one individual. The story of you or me, totally and utterly insignificant people, caught up in events we can neither control or understand, trying to survive, trying to protect those we love. The story’s told from one perspective, we don’t get that sweeping sense of multiple perspective epic fantasy has. That was very intentional – it’s the story of one woman’s experience , her life and her attempts to cope in the world. The book came out as a kind of howl of pain and rage during Covid lockdown – it’s very personal to me and my life. It’s written in a stream of consciousness, from inside Lidae’s mind at all times, and the things we see are in places deliberately unclear or wrong, because it’s how one person’s limited knowledge and bias and character interprets the world.

Empires of Dust starts off very much about men (I don’t think any women feature at all for the first maybe 50 pages??) and is very much about people with few responsibilities to those around them. Towards the end of the trilogy people talk about family and caring responsibilities and community more. Empires of Dust is very influenced by the life of Alexander the Great and by the Iliad. With A Woman of the Sword I was thinking about stories like the Antigone and the Medea, which explore women’s lives and domestic responsibilities as they deal with the consequences of these huge war and politics events.

TOM Back in September 2019 you were interviewed by Nightmarish conjurings. You told them that, after Empires of Dust you were “beginning to work on something which is actually more hopeful. It is more hopeful and redemptive on a personal level. It’s a much more human scale piece.“ However, no book is written in isolation from its context, and the dedication at the start of A Woman of the Sword –

“For all the mothers who got through the last few years”

alludes to some of the global turmoil that would have been a backdrop to that writing ambition of a hopeful and redemptive piece.

To what extent and in what ways did that global crisis context shape and change the writing and the form of the final story?

AS Hugely. As I said, the book was written during Covid (well, when the Covid lockdowns eased enough I had childcare again and thus time to write), then edited while staring in horror at images from the war in Ukraine. The experience of being a mother, a carer, trying to juggle everything and keep some semblance of normality for my children, was the only thing I could think about for a long time. Now I’m writing this interview haunted by the image of a man sitting quietly by a pile of rubble that’s all that’s left of his home, holding his dead daughter’s hand, refusing to let her go …

It’s a book about those small lives, the things that happen to people, some vast and terrible like pandemics and wars, some small and personal, but all shaping people’s lives. Parents right now in the UK are going hungry and sitting in the dark so they can afford to feed their children … and that means nothing to the people in power, doesn’t even register on their consciousnesses.

I reread Middlemarch early on in the pandemic as a comfort read, and the closing lines really hit home:

‘for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.’

Those things that history dismisses as unimportant but are the underpinning of everything , raising a child, caring for a vulnerable friend or relative, making some’s last agonising hours slightly easier … I suppose A Woman of the Sword is kind of about that, in a very sad dark way – the hidden lives, the unhistoric acts that the mighty ones like Marith simply sweep away.

And mothers – yes, lockdown had heavily gendered impacts, and I wanted to say that.

The book in the Nightmarish Conjurings interview is actually something else I can’t talk about yet that is genuinely more hopeful and redemptive. It’s linked to my story in Grimoak Press’s Unbound II which is a very hopeful and redemptive if frankly bizarre story and introduces something a bit new in my writing.

TOM Lidae’s struggles in A Woman of the Sword entangle themes of war and motherhood, particularly the self-perpetuating wastefulness of war, and the conflicts between career and a dutiful maternal love.

Tells a bit more about Lidae. What do you admire in her and what do you dislike? And more importantly do you love her or Marith more?

AS Oh, Marith is the love of my life and always will be. I’ve never quite got over having to end the trilogy, I could still happily be writing slash fiction about him.

Lidae is me. In fact, my feelings about Marith are pretty clearly there in her feelings about war and kings – she gets to do what I only dream of and live in the world I created, get caught up in it without the horrible pain of having to end the trilogy…

Lidae is very flawed. She’s uncertain, full of self-doubt, not a great mum. I wanted that to come across strongly, that she’s weak and sad and frightened. Because a lot of mothers are weak and frightened and self-doubting and frankly just exhausted to the point they have no patience left to be a good parents. I was a bloody awful mum for a lot of the pandemic, there’s a point a lot of us reached where you were just sitting on the floor with your hands stuffed in your mouth trying not scream because your children would hear and … where do you go from there? What can you do at that point? I had severe post-natal depression, I find parenting very hard and frightening. It’s the greatest joy of my life, but also the worst part of my life.

I don’t think I admire her, but I care very deeply about her. She’s a much better, stronger person than she realises.

TOM Some might argue that your writing style is more ‘literary fiction’ than ‘genre fiction.’ Indeed the UK Times described The Empires of Dust as a “Game of Literary Thrones.” Others might say that literary fiction is itself just a genre.

How do you see yourself and A Woman of the Sword fitting into the landscape of literary/genre writers and writing?

AS I would consider what I write literary fiction, it makes me hugely angry that fantasy doesn’t get the same regard that science fiction or historical fiction does. The shock in the literary pages when Marlon James announced he was writing a fantasy trilogy after A History of Seven Killings … it was painful. Fantasy is so dismissed – but it’s the oldest genre of stories there is, the Iliad is fantasy, Gilgamesh is fantasy, Beowulf, the Mabinogion, the Mahabharata – people have been telling stories of gods and monsters and magic and wonders probably since before modern humans existed. So why shouldn’t we claim the literary high ground?

Fantasy gives so much scope for exploring a world, making it different to ours, having people think and feel in different ways. To push the bounds of what language can do, describe magic, horror, wonder, things outside all normal experience. To push description to the limit. It can and should be a hugely literary, yes.

TOM Staying on the theme of literary fiction, Amitav Ghosh in The Great Derangement observes that literary fiction has not engaged effectively or fully with the developing climate crisis. There is a question about how far literature can or should engage in the political issues of the day, and I know that you have strong political opinions. It was quite shocking actually to read the prescience of your observation in interview to the Crows Magazine back in April 2020

“The outpouring of support for nurses, careworkers, cleaners in the last few weeks has been wonderful. It’s also been laughable – the people who mop the shit off hospital floors are important, who knew? – and I suspect it will mysteriously disappear again as soon as this is over in favour of ‘fiscal discipline’ and other delightful gaslighting ways of saying the poor stay poor the rich stay rich. We’ll give our medical heroes a big shiny cheer as angels and tell them sadly the need for grown-up economic restraint says we can’t give them a pay rise so f-off and stop being all girly over-emotional.”

How far can fiction in any genre hope to shift popular attitudes, e.g. by slipping a progressive message into a fantasy narrative, or is polarisation pre-embedded in people’s reading choices so authors are always ‘preaching’ to their own choir rather than reaching a broader target audience?

AS I had forgotten I said that! But yes, it’s so predictable. And so predictable that a lot of people seem to be accepting it. That phrase ‘grown up conversation’ is hideous … flung out to mean stop talking about stuff like family life and feelings and lived experience. Those childish petty insignificant things.

I slipped some stuff about environmental collapse into Empires of Dust, in fact, the environmental impact of Marith’s wars.

I’d like to think people read my books and see things a bit differently. I think a few people did from the messages I receive. And occasionally there’s this glorious moment in a Bakker fan group I’m in you can see someone go from ‘It’s about what if Jordon Peterson was Aragorn! Woo!’ to ‘Ohhhh shit it’s about what if Jordon Peterson was Aragorn … woooooo….’ I think Thalia’s opening monologue in The House of Sacrifice maybe had a bit of an impact on some people. I hope. But from the hate mail I’ve had, others are going to read a bit, realise it’s a bit more complicated that straight white alpha males being alpha wayhay, put the book down and copy me into a one star because it has gay people in it review.

Are they the ones who need to read A Woman of the Sword? Obviously, yes. Are they going to read a book called A Woman of the Sword? Obviously, no.

TOM Authors vary enormously in their approach and their routines. Some are plotsters, mapping out every scene in detail before even writing an opening line, others are pantsters just letting the words spill out onto the page and have the story and characters lead them.

Where on the plotster/pantster continuum do you see yourself?

AS I start as a total pantster, a scene comes into my head, a landscape with a person or persons in it, and I write with no idea who they are or what’s happening. Chapter two of The Court of Broken Knives was just me seeing these men in a desert, no idea why, then the dragon turned up, then there was this other guy in a city, no clue how they connected. The second chapter of A Woman of the Sword was me seeing a place and a woman in it, I had no clue what would happen to her after that first scene. It’s an amazing process of discovery. And then usually maybe 20,000 words in I see the whole thing, suddenly understand what I’m writing and why, and then it’s a matter of finding it. Kind of like I’m letting the book write itself through me, it finds me and writes itself out. So I know the end and the character arcs, and roughly how get there, but things still surprise me as I write them. The world unfolds itself as well, and the characters’ backstories, I discover everything as I go along. It clogs up my head totally but it’s all there in my head sort of dumped there and I can see it.

Unless I can’t find it, in which case it’s pain and hell and I feel physically and mentally wrong until I make the right connection and find what it is I’m supposed to be writing.

TOM Stephen King famously professes a very disciplined approach to writing, devoting every morning to writing and then taking the afternoons and evenings off. Others have a less structured, more mood based writing regime.

Can you tell us a bit about your how your writing routines and processes have developed over the years? Do you have any tips for overcoming writer’s block?

AS My writing routines … ah aha ha ha. I supposedly write two days a week and other days when I can. In reality I write two days a week if my children are miraculously both in school with no special assemblies I have to go happening, and if I don’t need to urgently spend all day sourcing a new PE jumper, fashioning a model of an Anderson Shelter out of matchsticks and researching maths tutors. I don’t actually write very much per week, basically, because my life is getting in the way too much. A lot of (male) writers talk about getting into the routine of writing every day, suggest forcing yourself to get up early or write late at night if you really can’t find time in the normal day– which is fine unless your children always wake up the moment you do, or refuse to go to bed until you do, and unless you’re so crushed to a pulp by life that getting up early or saying up late would leave you writing literally nonsense than falling asleep at the wheel during the school run. I tried getting up at five am to write for a while – my daughter woke up the minute I did, after two weeks we were both gibbering wreaks, and when I read the novel I’d tried to write it was garbage.

Write where and when you can, and write if and when you enjoy it. Try to write often, but don’t stress if a week goes by and life was more important (it is. Caring responsibilities, or being there for your best friend, or just paying the bills while also getting a chance to relax with your friends and family occasionally or just curling up and chilling out because you’re exhausted really are more important). But trying thinking about the writing as much as you can, build it in your head, so when you do write you can let it flow without the blank page staring at you taunting you because you have no idea what to write.

And stay off social media and surfing the internet. When you do get a chance to write, don’t waste it.

TOM A Woman of the Sword is being released by Luna Press Publishing, a relatively young (but already award winning) imprint, with a slant towards speculative fiction.

Can you tell us a bit about how you found Luna Press – or how they found you?

AS I’m honoured to be working with Luna. I’ve known Francesca for years through FantasyCon and greatly what she’s doing in publishing complex, progressive voices in SFF. A Woman of the Sword was never going to be Big Five material, and Luna seemed the idea fit. The book had to be published by a feminist-slanted, female-run publisher really.

TOM While the saying may advise against judging a book by its cover, A Woman of the Sword does have a luscious cover designed by Stas Borodin.

You have shared some images from different stages in the cover design process on social media.

Can you tell us about how much involvement you got in the cover process? (Did you get to deliver a design brief?) and what led you and/or your publisher to embrace the final design?

AS I was very involved, and actually suggested Stas to Luna. He gets me completely, some of the pictures he created for Empires of Dust astonished me they were so close to what I could see when I was writing. I gave Stas the design brief ‘like a classic Sword and Sorcery novel but with a mum instead of Conan’ and a copy of the manuscript – and he knew. The cover is perfect. My mum cried when she saw it. So many people have responded to it as capturing something special.

TOM In your fulsome acknowledgements you give a slightly apologetic shout out to Ian Drury your agent for his “faith in the book despite it not <quite> meeting his brief as a mainstream commercial blockbuster.”

What would be your commercial elevator pitch for A Woman of the Sword?

AS Ha, I have done this pitch! If Elena Ferrante was a Bridgeburner. Venn diagram of four people for whom that is literally the book they’ve dreamed of all their life.

TOM As I read and enjoyed A Woman of the Sword I found it threw up lots of associations and connections, for example from Shakespeare Richard of Gloucester’s complaint about the Weak piping time of peace, or Mark Anthony’s promise to Caesar’s corpse that Fierce civil strife shall cumber all the parts of Italy. Then there was Buffy Sainte Marie’s song about The Universal Soldier, and – having just seen a production at the Bord Gais in Dublin, Willy Russell’s musical of sibling and maternal torment Blood Brothers.

Were there any particular literary influences that helped inspire you in writing A Woman of the Sword?

AS Most obviously, there are repeat references to the Wasteland, which is a poem that obsesses me and sort of sits in the back of my head all the time. All the themes of memory, the past and especially the First World War, the terrible sense of grief, the very sense of a wasteland …. And Lidae herself is quite unstable as a character, she has different facets to herself, different voices, she’s as much a ghost of her own past as a person living now in the present.

A huge influence was Brecht’s Mother Courage. The subtler women in A Woman of the Sword are a signpost to that. I saw Fiona Shaw as Mother Courage years ago, it was a pretty formative experience (actually, thinking about it, seeing Fiona Shaw recite the Wasteland was another formative experience…). Lidae is very much drawn from Mother Courage and the source text The Adventures of Simplicius Simplicissimus which is about ordinary people’s lives during the Thirty Years War.

I mentioned the Antigone and the Medea, which were huge influences. That line of Medea’s: ‘rather would I stand three times in the line of battle than give birth to just one child’. I think House of the Dragon went with that line in a rather too literal way …. I love authors like Philippa Gregory who write about women’s domestic and sexual lives against a backdrop of huge events, the struggles of marriage, childbearing and infertility, sexual desire, self-expression. Her White Queen for example, or Three Sisters, Three Queens. Really brilliant books – but about queens and noble women, not ordinary women.

TOM I have delighted in the many friends and connections I have made through a shared love of speculative fiction, and your acknowledgements pay tribute to many names within that online and (at conventions) in person community. There are authors who have inspired you, publishers who have supported you, and friends and readers who have been commemorated in depictions within A Woman of the Sword. The fantasy community at times feels like the kind of extended found family that is itself a popular trope within fantasy fiction.

Would you like to elaborate on any of the call outs from acknowledgements? And do you think that the nature of speculative fiction creates a uniquely supportive community, or would romance, crime, and young-adult genres be able to show similar engagement from their followings?

AS I have no idea about other genres, I’m afraid. I’m told romance conventions can be pretty bitchy but that’s hearsay. I suppose the inherent untrendiness of fantasy that I was complaining about above helps, there’s something about being in a room with a bunch of other people who share your very unhip love of dwarves and elves that’s special. When you meet another elegantly dressed professional woman and mum of two who gets weak knee’d at the mere words ‘dragon knight’ … you feel a bond there it’s hard to break. The community is a found family for me– the reason my acknowledgements are so fulsome is that I never really had friends of my own until I found the fantasy community at cons. My life revolves around epic fantasy, ancient history and experimental folk music, and I genuinely believe in King Arthur, the Wild Hunt and the Dark Is Rising: it’s never been particularly easy to chat to mums at the school gates about shared interests. Then I finally went to my first fantasy convention.

A Woman of the Sword is due for release 4th April from Luna Press Publishing. You can pre-order your copy HERE