EMBASSYTOWN by China Mieville (Book Review)

Embassytown: a city of contradictions on the outskirts of the universe.

Avice is an immerser, a traveller on the immer, the sea of space and time below the everyday, now returned to her birth planet. Here on Arieka, Humans are not the only intelligent life, and Avice has a rare bond with the natives, the enigmatic Hosts – who cannot lie.

Only a tiny cadre of unique human Ambassadors can speak Language, and connect the two communities. But an unimaginable new arrival has come to Embassytown. And when this Ambassador speaks, everything changes.

Catastrophe looms. Avice knows the only hope is for her to speak directly to the alien Hosts.

And that is impossible.

I finished Embassytown with many thoughts buzzing through my head and a need to write them down. Mieville has a wonderfully immersive writing style through which the reader discovers the worlds he creates by page turning experience rather than upfront exposition. While that ensures everything at the start is a mystery it also means that this review will end up quite spoilery. So I will try to divide it into ‘mildly spoilery’ and ‘really spoilery’ sections.

Mildly Spoilery (about worldbuilding and setup)

In Embassytown, Mieville gives us a superficially familiar trope of a colonial outpost of humans on a planet inhabited by a very different indigenous species – the Areikie or Hosts – with whom they need to foster and maintain trade links. As such it reminded me of the European Legations in Beijing during the 19th Century. There are parallels to the East-West culture clash and the linguistic challenges of mastering Asian languages whose tonal nature makes learning them much harder than moving between European romance languages. The Areikien Language adds several additional dimensions to those kind of linguistic challenges, and so forms the spine of the plot. Everything pivots around the need to communicate with the Areikie, how to find ‘Ambassadors’ capable of doing so, and what happens when that communication goes wrong.

There are also parallels with the socio-political tension that arose from the Western powers’ determination to maintain a hugely profitable opium trade into China making addicts of so many of the population. Two opium wars and one Boxer rebellion highlighted the physical isolation of the Legations, waiting desperately for relief from their powerful but distant home countries. Embassytown, like the Legations – is dangerously cut off – when the shit inevitably hits the fan. With a long and despairing wait for the next scheduled ship to arrive, they are very much on their own.

Mieville gives us a compelling first-person protagonist in the space-travelling, one time simile and future metaphor Avice Benner Cho. Avice stands at the intersection between multiple Venn diagrams. She is both a native of Embassytown having been born and spent her childhood there, but she is also experienced in the ‘Out’ having demonstrated the rare but profitable skills needed to crew ships making the long hazardous journeys between the stars. She is part of the human community (The Terran diaspora), but she also holds something of a celebrity status with the Hosts having been used in a strange linguistic performance to become a simile (one of several which are necessary in the development of their Language). She is a private citizen, on a career break from space travelling, but also by virtue of her experience in the Out has enough status to make her voice heard and to mingle with Staff in the Embassy’s corridors of power. She is in short, uniquely placed both to narrate unfolding events and to attempt to steer their course.

Mieville gives us a compelling first-person protagonist in the space-travelling, one time simile and future metaphor Avice Benner Cho. Avice stands at the intersection between multiple Venn diagrams. She is both a native of Embassytown having been born and spent her childhood there, but she is also experienced in the ‘Out’ having demonstrated the rare but profitable skills needed to crew ships making the long hazardous journeys between the stars. She is part of the human community (The Terran diaspora), but she also holds something of a celebrity status with the Hosts having been used in a strange linguistic performance to become a simile (one of several which are necessary in the development of their Language). She is a private citizen, on a career break from space travelling, but also by virtue of her experience in the Out has enough status to make her voice heard and to mingle with Staff in the Embassy’s corridors of power. She is in short, uniquely placed both to narrate unfolding events and to attempt to steer their course.

I have seen one Goodreads reviewer[i] observe, somewhat testily, that Avice’s spacefaring skills are ultimately irrelevant to the plot. Mieville does devote some lush description to the Immer (a more haunted and dangerous version of what Dan Simmons might call the Void and others might term Hyperspace). Here only Avice and her crew mates’ tolerance for the immer and their resistance to the crippling sickness it produces enable them to handle the ship through the immer. They navigate by beacons or lighthouses that are older than our universe, and take care to avoid the denizens of the place. As Avice notes of her travels through the immer “we moved in what were not really directions” and they shake off the swarming Hai with “assertion charges.” In short, the Immer would be a rich enough place for a story to explore and I can sympathise with readers annoyed that the narrative never returns there.

However, Avice’s Immer career is very relevant to the story. It is how Avice meets her fourth spouse the linguaphile Scile and at his urging, she brings him back to Embassytown – the childhood backwater she had escaped – to indulge his curiosity about Language. Here Scile – the outsider – becomes one catalyst in the unfolding events, while Avice’s financial independence and experience in the ‘Out’ enhance her status and ability to play a role within Embassytown.

The immer also generates one of my favourite lines as space travel and time dilation render the normal recording of age somewhat irrelevant. Avice notes that “When I was seven years old I left Embassytown…I returned when I was eleven: Married, not rich, but with savings and a bit of property.” But as one immer officer tells her

“I don’t give two shits about whatever your pisspot home’s sidereal shenanigans are, I want to know how old you are.”

Which brings us to the Embassytown convention of measuring age in kilohours – which sent me hoking for a calculator. (One standard earth year is 8.766 kh which means Avice left Embassytown aged 19.5 Earth years and returned at 30.7 Earth years – though Mieville’s intext reference to anyone who would calculate in Earth years is rather scathing![ii])

The Areikie themselves are a strange insectoid race that pass through four life stages or istar, of which the third is adult and the fourth is an age of respected senile dementia. Mieville does not attempt a full description of the creatures, but teases the reader with glimpses of detail, mentions of “fanwings” and “dainty chitin steps” and “carapaces” and “hooves.” They breathe different air, that is toxic to humans so the whole of the Embassytown enclave must be shrouded in an artificially generated bubble of breathable air and those who would venture into the wider Host/Areikie City – still less the continental hinterland beyond – must wear organic breathing masks or aeoli.

The masks are one example of the organic or bio-rigged nature of Areikie technology. Their houses are living things, their factories creatures that vomit products to order. The bio-technology reminded me of the Zygons[iii] in Dr Who with their strangely organic spaceship. For Embassytown though, this biotechnology is a key trade good, particularly where it can be combined with terran technology to make new weapons and machines.

This enhances the strategic significance of Embassytown as a colony of the wider Bremen confederation and there is tension as the colony aspires for more independence based on the unique ability of its homegrown ambassadors to not simply negotiate – but more fundamentally to communicate with the Areikie.

And it is in communication and language, or rather Language that Mieville’s world and plot gets very creative. I have admired Adrian Tchaikovsky’s imaginings of other languages such as the web-tapping spiders in Children of Time and the emotionally coloured octopuses in Children of Ruin, but the Areikie are on a quite different level, or should I say pair of levels. For the Areikie each have two mouths and speak using both simultaneously – one voice being termed the cut and the other the turn, working in harmony. However, speaking to the Areikie requires more than just having two people trained to make the right sounds at the same time. In the same way as Frankenstein found that assembling body parts in the correct order and configuration did not make a living being, so too for the Areikie sound alone, no matter how precisely it mimics their own speech, is not communication.

As Scile explains

“…to them it means nothing because it’s only sound and that’s not where the meaning lives. It needs a mind behind it.”

And Avice emphasises

“A Host could understand nothing not spoken in Language, by a speaker, with intent, with a mind behind the words.”

And while two people could supply two mouths to make the right noises, they could not do so with the single mind necessary to give the sound meaning.

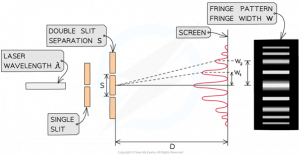

That bit reminded me (somewhat tangentially) of an A’level Physics Experiment called Young’s Slits.[iv] Light from two sources (slits) can produce a stable interference pattern of light and dark bands on a screen, but only if the two light sources are “coherent” which usually means you derive the two slit sources from a single origin.

(retrieved from https://www.coursehero.com/study-guides/physics/27-3-youngs-double-slit-experiment/ )

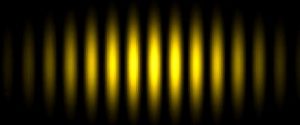

By shining one light at the two slits you can ensure that the light passing on through both slits is “coherent” and so able to produce stable interference patterns of alternating light and dark bands rather than a shifting blur.

(retrieved from https://www.coursehero.com/study-guides/physics/27-3-youngs-double-slit-experiment/ )

Just as that experiment needs a single coherent source shining through two slits to produce patterns, Language requires a single coherent mind speaking through two mouths to produce meaning.

Embassytown needs specialised pairs of speakers acting as a coherent or conjoined-intent couple to be ambassadors to the Areikie. Their solution is to grow sets of cloned twins in a nursery and train them to be able to act as a single entity within two bodies. Something a little more complex – but not quite as spine tingling – as having Simon and Garfunkel sing in harmony . So the Ambassadors of Embassytown are all pairs. Avice’s sometime lover(s) are/is Ambassador CalVin, or Cal and Vin but so identical she can never be quite sure which one she is talking to, or which one is loving her.

But besides this bifurcated nature of Areikie Language, there is a second complication – a literal or non-representative aspect to Language. The Areikie can only speak of things that exist and are true, which means they cannot lie, any more than we humans can fly. They are amused – fascinated even – by the concept of lying and even hold a glorious ‘Festival of Lies’ where the ambassadors entertain them with simple lies such as stating in Language that a red object is blue. The Areikie also enjoy having a go at lying themselves, though even the mild dissemblance of miscolouring an object requires rhetorical contortions, soft spoke equivocation and even the assistance of others to say the true part before the Areikie can even come close to saying an untruth.

In our post-truth society peppered with industrial scale liars like Johnson and Trump, I find a certain poignancy in a species for which lying is impossible.

The third complication Mieville throws into the mix is the Areikie’s need for similes to aid their communication. It’s slightly fudgey concept but involves human ‘performing’ a simile in order to open up the Areikes’ ability to communicate new ideas by reference to that real physical simile/person. As a child Avice played a part in performing one such simile and as such she is not just a person but also a part of Language – a living physical figure of speech you might say – which is why she has a certain celebrity status within the Host community.

The contortions it takes to create Ambassadors who can speak Language, the Areikie’s inability to lie, and Avice’s erstwhile role as a simile all converge as Embassytown faces a grave peril.

Really Spoilery (about plot and resolution)

Having set up this strange concept of identical twin/cloned ambassadors, Mieville then subverts it by having Bremen – the colonial power – send out its own ambassador pair, not bred or trained in Embassytown and not even identical. Ambassador EzRa is more a Laurel and Hardy pairing than Mary-Kate and Ashley.

Despite their differences EzRa has passed every test of an ability not just to speak Language, but do so with that synchronised coherent intent that will make their speech intelligible to the Areikie. However, the Language they speak, while intelligible is tainted by some imperfection that makes it utterly intoxicating to the Areikie. They become drugged into insensibility by the sound of EzRa’s voice and cannot wait to get another fix of it. Instead of negotiating trade deals EzRa becomes a peddler of a Language drug to a city of desperate and determined addicts. This reminded me of John Cleese and Jamie-Lee Curtis in the film A Fish Called Wanda where Cleese’s ability to speak fluent Russian and Italian turned him from mild and unprepossessing solicitor into an irresistible sexual magnet as Curtis writhes at the mere sound of foreign syllables (The Magic of accents ). In the same way EzRa’s recitation of a shopping list would still be drug enough for the addicted Areikie.

The Host City stutters into stupefaction with its living buildings and machines, all so essential to maintaining human life in Embassytown, groaning from neglect. The inhabitants of Embassytown, like those of the Western Legations besieged by the Boxer Rebellion in Bejing, must find a way to survive until the next (infrequent) relief ships arrives. But it is more than just the addicted Host that threaten their survival. Some Areikie take a path of self-mutilation to effectively deafen themselves to the drug of EzRa’s speech and then set about eradicating the humans so that the next generation can grow up on an Areika that has been cleansed of the taint and temptation of the drug-ambassador and his kind.

Ultimately the plot requires Avice to teach the Areikie how to lie. This is essential not just to break their addiction to EzRa’s mispoken Language, but to destroy their Language altogether and make them speak and communicate using language, a means of communication that can reference other objects and ideas which may or may not exist and which may or may not be true.

Now a smilie is broadly true – a comparison that says something is like something else. One of the Areikie’s rhetorical contortions in trying to lie was to use a simile to imply two very different objects are like/the same as each other – which is a sort of lie. However, Avice aspires to be more than a simile as she puts it

“I don’t want to be a simile anymore… I want to be a metaphor.”

And of course, a metaphor is a lie, where a simile is not. “His expression was like a raging storm” can be true, but “His expression was a raging storm” can not.

Embassytown is not a flawless book. The nature of action-packed space-operas demands desperate plans, knife-edge decisions and resolutions that unfold in a few pages. We demand that the Deathstar be blown up in an instant rather than painstakingly deconstructed for scrap over several years. The same reviewer who was disappointed by the narrative abandonment of Avice’s time in the immer also struggled with the resolution, disappointed in how it required the Host to make near instant adaptation to complex linguistic challenges that should have taken centuries of evolution to secure. He also objected to some logical inconsistencies that punched holes in the plot, such as how can one create a simile without already knowing what one wishes to create? If that kind of flaw unsuspends your disbelief, then fair enough (I’ve been put off books which flaunted cavalier attitudes to fundamental laws of physics, so each to his own).

However, Mieville is an immersive writer and it is a joy to wallow in his prose and savour his imaginative worldbuilding. And, just as Newton knew the inadequacies in his theory of Gravity (leaving that for Einstein to resolve) so too Mieville understands that using language to play with the concept of Language is an inherently doomed prospect. Carl Freedman notes Mievielle’s expressed views on the literal impossibility of humans authentically depicting an alien intelligence,

Mieville also maintains, in a way precisely coherent with the Aristotelian idea of a probable impossibility, that the attempt to do what cannot actually be done may nonetheless yield interesting and worthwhile results: “You can play games – you imply consciousness beyond ours, you can hint at things obliquely, you can not say too much. … I don’t think you can succeed but I think you might just fail pretty wonderfully.”[v]

The same argument also applies to his wrestling with the concept of Language. And as Avice says of the Areikie view of humans and human language “We’re insane, to them: we tell the truth with lies.”

Or as Neil Gaiman puts it in Art Matters and Embassytown exemplifies

“Fiction is the lie that tells the truth.”

[i] Review by Warwick on Goodreads on September 21 2012 https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/9265453-embassytown

[ii] On page 19 Mieville has Avice note “I once met a junior immerser from some self-hating backwater who reckoned in what he called “earth-years”, the risible fool.” – I guess that makes me a risible fool!

[iii] First introduced with the fourth doctor (Tom Baker) https://tardis.fandom.com/wiki/Terror_of_the_Zygons_(TV_story)

[iv] More on Young’s Slits experiment or the double slit experiment here https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Double-slit_experiment ,

[v] Quoted on p120 of Art and Idea in the Novels of China Mieville, Carl Freedman, Glyphi Limited, 2015