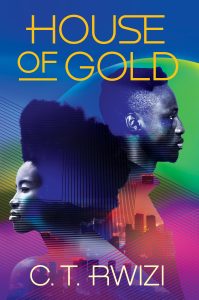

HOUSE OF GOLD by C.T.Rwizi (Book Review)

From visionary author C. T. Rwizi comes the epic journey of four people on a distant planet who face the ultimate test of loyalty, friendship, and duty in the rising tide of war. A corporate aristocracy descended from Africa rules a colony on a distant planet. Life here is easy—for the rarified and privileged few. The aristocrats enjoy a powerful cybernetic technology that extends their life spans and ensures their prosperity. Those who serve them suffer under a heavy hand. But within this ruthless society are agents of hope and change. In a secret underwater laboratory, a separatist cult has created a threat to the aristocracy. The Primes are highly intelligent, manipulative products of genetic engineering, designed to lead a rebellion. Enabling their mission are the Proxies, the Primes’ bodyguards and lifelong companions bound to their service. When the cult’s hideout is attacked, Proxies Nandipa and Hondo rush to the rescue. As they emerge with their Primes onto the surface, however, everything they’d been led to believe about their world is shattered. Nandipa and Hondo will risk it all to honor their oath of absolute loyalty. But when the very people they’re tasked to protect turn on each other, the Proxies must decide between those they were built to serve and the freedom to carve out their own destinies. And the fate of their planet may rest in their choice.

Both reader and protagonists are in for some surprising turns of events in C.T. Rwizi’s newest release, the far future set House of Gold. Just as Rwizi’s debut Scarlet Odyssey was “noteworthy for its African-inspired setting” (Library journal), his foray into science fiction draws on an African origin story, as one protagonist Hondo recalls it

“The story goes our ancestors left Africa on Old Earth centuries ago, crossing a long-range jump gate to a distant arm of the Milky Way and settling the habitable worlds scattered across what they called the Tanganyika star cluster.”

The aesthetics of House of Gold have the same lush African feel that we saw in Scarlett Odyssey, one which is sufficiently pervasive and immersive to become an unobtrusive backdrop, allowing the story and the characters to take centre stage.

The chapters alternate between two first person protagonists, Hondo and Nandipa who aren’t even the protagonists in their own stories. They are Proxies, each bred and nurtured in a strange deep sea experimental station to serve and protect their respective Primes, Jamal and Adaolisa. Where Hondo and Nandipa have been trained to provide muscle and a proven killer instinct, their primes are trained for intellect and leadership.

The first part of the book introduces us to the base, called simply the Habitat, where twenty-five Primes are engaged in a year-long war game as a form of combined training and test. It feels like they are playing a combination of Sid Meier’s Civilisation, the board games Risk or Diplomacy and even Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game. There are those elements of strategy, resource management, negotiation, and betrayal. However, each year the losing Prime and their Proxy are ‘recycled’ into gloop – which ups the stakes somewhat in the game. The process and the Primes and Proxies are overseen by masked Custodians which adds a certain Squid Game feel to the place. And, as with Squid Game, there are alliances to be made and broken, deals to be done, and murder to be committed in and out of the training environment. All of this makes Hondo and Nandipa each other’s antagonists. Which is kind of tense since Hondo is attracted to Nandipa and consequently hates Benjamin, the proxy she has occasionally shared more than a smile with.

The first part of the book introduces us to the base, called simply the Habitat, where twenty-five Primes are engaged in a year-long war game as a form of combined training and test. It feels like they are playing a combination of Sid Meier’s Civilisation, the board games Risk or Diplomacy and even Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game. There are those elements of strategy, resource management, negotiation, and betrayal. However, each year the losing Prime and their Proxy are ‘recycled’ into gloop – which ups the stakes somewhat in the game. The process and the Primes and Proxies are overseen by masked Custodians which adds a certain Squid Game feel to the place. And, as with Squid Game, there are alliances to be made and broken, deals to be done, and murder to be committed in and out of the training environment. All of this makes Hondo and Nandipa each other’s antagonists. Which is kind of tense since Hondo is attracted to Nandipa and consequently hates Benjamin, the proxy she has occasionally shared more than a smile with.

This deadly training is all in order to create ultimate warrior pairs – brains and brawn – who can be released onto the ruined surface of this world – Ile Wura (or House of Gold). In the aftermath of an AI disaster, a kind of savagery has overtaken the people of Ile Wura making them into crazed monsters subservient to cybernetically enhanced tyrants, apparently something like the ruined future Earth that Arnold Schwarzenegger’s various Terminators came back from.

However, just as reader and protagonists are settling in for an extended Hogwarts/Magician’s Guild style training school of rivalries playing out and expertise enhanced, Rwizi throws us all a curve ball that snatches Hondo, Jamal, Adaolisa and Nandipa from the Habitat and dumps them on the surface. There, they find Ile Wura is far from the ruined dystopia they were expecting and is in fact a rather civilised society, technologically advanced, with cities, skyscrapers, flying cars and mobile phones. More Blade Runner than The Road or a Mad Max environment that we were all expecting. It appears that someone has been lying.

As the quartet acclimatise to the double disorientation of leaving the Habitat and finding the world other than they expected, they realise there is still work they can do. They were genetically bred, enhanced and trained for purpose of disrupting the status quo. For all its superficially civilised attributes – the surface society of Ile Wura is still a dystopia, a corporate dystopia that is in need of a bit of serious disruption.

The primes and their proxies’ genetically-engineered enhancements, besides intellectual and physical, and the skills of coding and combat, include a sensitivity to the thoughts and emotions of others. It’s not quite mind reading, but an awareness of nearby emotional states as a kind of static, that is useful – but not infallible – in telling where assailants are and anticipating reactions. It’s not quite a superpower, but makes for an interesting augmentation that helps explain the ability of four people on take on the might of an oppressive corporate state.

Hondo and Nandipa’s developing feelings for each other create a potential for conflict with their absolute duty, loyalty and indeed love for their Primes. In the Habitat Primes and Proxies were raised in separate groups until age 7 and then the Proxies each met their Primes for the first time and were given names by them (Hondo means War, and Nandipa means a gift given by a higher power). The bond between the Proxy and Prime is as strong say, as that between Sam and Frodo, though Hondo and Nandipa are both far more lethal killing machines than the Shire’s foremost gardener. As long as Jamal and Adaolisa remain aligned on strategy Hondo and Nandipa can enjoy a growing closeness. However, when – as with the War Games in the habitat – the two primes diverge in their approach and become competitors driven by different motivations, Hondo and Nandipa face hard choices and tested loyalties.

Rwizi plays with his protagonists’ sense of self, of purpose, of free will or of guilt, as Hondo reflects on his Prime developing other loyalties.

“From the beginning Jamal has wanted someone who believes in his cause, and I’ve only ever been someone who believes in keeping him alive. I’m not enough for him anymore. … It’s selfish of me, but I don’t think I ever want him to stop needing me. Because then, what would be the point of my existence.”

Or as another proxy tells Nandipa

He watches me, then says, “I’ve killed people, too, you know. Doesn’t have to change who you are.”

As Jamal and Adaolisa work in different and increasingly incompatible ways to bring down the seven corporation hegemony that rules Ile Wura, Rwizi spares us too intricate a vision of their clever hacking, espionage and subterfuge. Instead we get the shield-bearers’ perspectives, sometimes agents of their Prime’s destructive plans, sometimes desperate protectors when the Primes’ overreaching ambitions expose them to danger. It makes for a comfortably enigmatic narrative that rattles along at a good pace.

Rziwi’s writing is littered with sharp turns of phrase and evocative descriptions.

On an unlikely and untrusted ally

“Even the Free People don’t trust him; otherwise why would Patience stick to him like a fly on fresh shit.”

Or when approaching the boss level encounter

“The facility is indeed located on a remote island, an impressive structure of glass and bone-white cement cascading down the side of a rounded hill.”

While there are other worlds in the Tanganyika cluster – and spaceships do travel, somewhat slowly between them, Rwizi’s story stays rooted on Ile Wura. There a centuries old external crisis has been leveraged by corporate powers, and the elite who drive them, to subvert democracy and then wholly displace democratic rulership. Much as the world of street vendors, skyscrapers, cashless cards and flying cars feels comfortably near future rather than far future, corporations subverting democracy feels positively contemporary – to my eye at least.

The people of Ile Wura are stuck in a poverty trap desperately seeking Scree, a form of social credits that determines their usefulness as a member of society. Certain threshold levels of scree, Bronze, Silver, Gold etc are required if one is access better neighbourhoods, or even spend money in certain shops. It reminded me a bit of Ross Clark’s The Denial which imagined a world where environmental credits were required to access quotidian aspects of life – without a verified climate pledge one couldn’t spend money or reserve a hotel room. The use of scree and the corruption in its calculation traps people in low scree levels and makes a useful analogue for the various forms of self-perpetuating privilege that we see in contemporary society.

For the Oloye, at the end of a lifespan of almost Numenorian enhancement, immortality beckons, with the potential to be electronically uploaded to the Abode, a kind of heavenly version of the Matrix with echoes of the TV series Upload, but an immortality built on a terrible human cost.

Besides scree manipulation, the Oloye maintain their grip on power by manipulating different gangster gangs to police the slums and fight each other and the people remain trapped by the Gaslighting tactics[i] of capitalism with Jamal’s arthritic barber asserting

“I just gotta work harder. That’s all.”

As Jamal scathingly notes

“The human capacity for self-deception is astounding, isn’t it?” he says. “That poor old man lives in a society advanced enough to extend his life indefinitely yet instead chooses to make his arthritis treatments unattainable; and he thinks the solution is to work harder.”

“It’s all he’s ever known,” I say in the barber’s defense. “It’s what he’s been told his whole life.”

In House of Gold Rwizi poses some interesting questions about how best one should create change in an unjust and unsustainable system. Is it through the bloody swell of revolution, like France in 1789, or is it through seizing and using existing levers of power such as in Great Britain with the Great Reform Act of 1832?

Jamal and Adaolisa stand on opposite sides of that debate and it is one that confronts our world as we struggle against ill-treatment of refugees, the growing corporate driven climate crisis, and authoritarian attacks on democracy. Government and media demand a kind of Schrodinger’s protest, disturbances that do not disturb, protests that are not so loud they might be heard. Rwizi’s House of Gold presents a fable about overthrowing an unjust and self-protecting elite, that resonates sharply with what I see around me and the paradox of protest for meaningful change.

As Adaolisa observes,

“This world is a powder keg waiting to go off. It would be so easy for Jamal to light the fire and make things worse. I’m not specifically trying to stop him. I think we both seek the same end. But I want to make sure there’s something still standing when all is said and done.”

Which is what makes her unsure of Jamal’s determination to eliminate the Oloye arguing that

“…tyranny isn’t just an individual or a group of individuals. It’s a culture. It’s endemic. A system whose roots of complacency, corruption, and hopelessness extend across every level of society. The faces of the tyrants themselves are almost always arbitrary; remove one, and another will rise to take their place.”

The plot braids together the two strands of the growing but tense affection between Hondo and Napinda, and the political paradigm shift being plotted by Jamal and Adaolisa in an intriguing mix. There are some plot points which might not bear too close a scrutiny – particularly around one character’s disappearance and the manner of his reappearance – but the whole makes for a tense futuristic thriller washed down with a dash of will-they won’t-they romance.

I find a certain delicious (deliberate) irony that this indictment of corporate tyranny and its subversion of democracy and peoples rights and dignity is published by 47North – which is of course an imprint run by Amazon – one of the largest corporations in our world, with its own issues of worker exploitation.

However, solutions to this as to other problems are neither simple nor instant. As one character observes when Ile Wura appears to be back on the road to democracy,

“Just because they get to vote doesn’t mean their lives will suddenly be better.”

(But you should still use that vote!)

[i] I was going to use the term Stockholm Syndrome here, a term coined by Swedish Psychologist Nils Bejerot to describe victims of a hostage situation who became aligned with and sympathetic to their captors or persecutors. However, Bejerot’s analysis was debunked by one of the victims Kristin Enmark who was very critical of Bejerot and the Police for how their approaches had endangered the hostages. Enmark asserted that she had been strategically seeking a rapport with the captors. Bejerot’s invention of the term may have been a misogynistic attempt to belittle a victim’s criticism of his own professionalism. However, in this context Gaslighting is more appropriate for the way that libertarian capitalism works to persuade people that (a) work inevitably earns and deserves its own rewards, and that therefore (b) all rewards/privileges of the elite are also earned and deserved.

House of Gold is out now and available here!