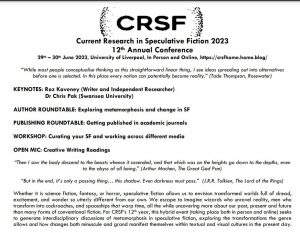

CURRENT RESEARCH IN SPECULATIVE FICTION (CRSF) 2023 – Conference Report

Once again, as June drew to a close, delegates from across the globe gathered in the sunshine filled School of the Arts Library at Liverpool University for another hybrid conference interrogating the range and reach of speculative fiction. The focus of the twelfth CRSF conference was on Transformations – but, as the call for papers made clear this theme was a broad umbrella looking at transformations of bodies, cultures and worlds.

Once again, as June drew to a close, delegates from across the globe gathered in the sunshine filled School of the Arts Library at Liverpool University for another hybrid conference interrogating the range and reach of speculative fiction. The focus of the twelfth CRSF conference was on Transformations – but, as the call for papers made clear this theme was a broad umbrella looking at transformations of bodies, cultures and worlds.

Consequently, the team received a range of abstract submissions that were as diverse in their concepts as they were in their geographic origins.

As with the 2022 conference, CRSF again went hybrid with most sessions involving a mix of online and in-person presentations broadcast both within the rooms and – through the magic of Zoom – to virtual attendees across the globe. Once again the team were indebted to The Olaf Stapledon Centre for generous funding; despite the elegant amenities, distinguished key note speakers and plentiful refreshments catering to all dietary needs – there was no charge to attend the conference. The committee also appreciated the support and encouragement from The Science Fiction Foundation which, through its activities and its academic journal Foundation has been a forthright advocate for speculative fiction for over 50 years.

With multiple sessions running simultaneously it was impossible to attend all of them. Consequently there are many great sessions and presentations that I’m simply not able to comment on – for example the panel on gestation and gender which, by all reports was fascinating. However, I hope through mentioning the ones I did get to, that I can convey some sense of what was a great conference.

Day One – 29th June

In the opening panel on Decentralising the Human Voice, David Tierney juxtaposed talking animals and silent humans in an interrogation of Agustina Bazterrica’s depiction of normalised cannibalism in Tender is the Flesh and his own practice-based research work Ark, where humans, animals and cybernetically augmented animals are drawn into murder on a farm. If Bazterrica’s loss of language in the bred-for-food humans known as ‘heads’ dehumanises them to the point where they can by reduced to food and/or surrogate vessels – would animals able to speak become humanised, and how would that strangeness of animal speaking be conveyed?

Dr Laura-Jane Devanny also looked at animal language in Laura Jean McKay’s Animals in that Country where a plague has – bizarrely – given infected humans the ability to understand and communicate with animals. This then has them question the hierarchies of use and abuse that they had subjected what were once ‘dumb’ animals to. Her presentation looked at how McKay conveyed the rich varied texture of animal communication. The presentation raised questions about the degree to which the human voice, its words and syntax, conveys privilege and superiority in a binary division between language and non-language, rather than acknowledging a multi-dimensional continuum of sensory communication. Referring to the dingo protagonist of Animals in that Country Dr Devanny observed that “her voice isn’t made of words.”

Then Rowena Murphy read her intriguing piece of creative writing inspired by and taking aim at rapacious landlords. As the prose flowed smoothly from an initial sense of simple poverty into something altogether more horrific and alien, we found the session had come full circle with a return to the commodification of human flesh.

The next session was a round table on the thorny problem of Getting Your Academic work published. Alex Carabine as chair, efficiently managed the entertaining Q&A to draw on the considerable expertise and insights of the panel of four: Dr Paul March Russell (editor of Foundation ); Andrew M Butler (former editor of Vector – the critical magazine of the British Science Fiction Association); Charul (Chuckie) Palmer-Patel (founder and head editor of Fantastika Journal ) and CRSF (and the Fantasy Hive)’s own Jonathan Thornton (reviews editor for Foundation and reviewer for www.tor.com amongst many others).

As with any submission process, the panel emphasised the need to read and abide by the journal’s submission guidelines. Once received, papers go through an in-house check of basic compliance, relevance and appropriateness before being sent out to two peer reviewers. Given that peer reviewers are giving their time for free the turn-around time is not necessarily a short one and anything less than three months from reception to publication would be exceptionally short. In practice the gestation period of an article can easily be up to a year, especially when there are redrafts and responses to peer review comments to take into account. Alex asked about red flags and got several interesting responses, for example be aware of context and don’t labour over describing matters that are well known enough to be axiomatic within the community. However, above all else have a thesis argument, such that a reader can understand what point is being made and consider how evidence is used to support that point. For book reviews, which don’t have a peer review process, the turnaround will be shorter but again as always – abide by submission guidelines.

After lunch the next set of panels included one on Dreams, Surveillance and Change with a rare non-hybrid trio speakers who all presented in person. Jordan Casstles delivered a complex presentation, a Sermon on navigating the shrieking spiral at the heart of theory fiction which touched on thermodynamics as well as different branches of theory fiction and railed against the observed fact that “there are many ways to respond to the nihilism that is synonymous with modernity but they tend to take two prevailing forms, fascism and despair.” In referencing Hassan “there is no single authorised version of reality” Jordan drew the audience into a performative presentation where successive slides appeared to be subverting the presenter’s intention with apparent edits and redactions.

Victor Rees then delivered a paper The Stuttering Alchemist on transformational disfluency in the Vorrh novels of Brian Catling. Caitling’s polymath talent drawing on poetry and art and performance brought him relatively late in life to his debut novel. Victor interrogated examples of neologistic and phonological asphasia where Caitling’s writing allowed language to be warped and twisted through distorted words – recognisable by the syllables they shared with a target word, but becoming non-words estranged from the reader’s expectations by the intrusion of extraneous sounds.

Concluding the panel, Soenke Parpart spoke about Dreamscapes of Political Transformation in relation to Der Orchideengarten a short relatively short-lived literary fantasy magazine that ran for 51 issues in the first couple of years of the Weimar Republic. While Der Orchideengarten may lay claim to being the first fantasy magazine, its founding editors were politically conservative and commercially motivated. The magazine foundered as it fell foul of obscenity law fines and rising printing costs – while the editors drifted towards Nazi-ism. Soenke explored how some stories within the publication anticipated fascist ideology, and in the xenophobia they presented within a dream sequence infected narrator and reader with paranoia.

In the next session, Jonathan Thornton chaired a workshop conducted by Kate Heffner and Cait Coker on Curating a collection which looked at the ‘hows’ and the ‘whys’ of science fiction curation. They highlighted the necessity of rigour in curating materials with reference to the Carl Brandon controversy – an invented black SFF fan created by white fans in the 1950s to make fanzines appear diverse. Following an informative presentation online and in-person attendees were invited to share in group discussions their own collecting habits and preferences. Prompt questions helped focus minds: what do you collect?; what attributes do you look for (eg rarity/interest)?; how do you preserve/showcase your collection?; why do you collect? For some attendees the answers seemed to be a bit shoe-centric.

My final panel session of the day was on Destabilising Climate Fiction which I was rather compelled to attend on account of delivering one of the papers. In keeping with global nature of climate change this panel had the most geographically dispersed speakers.

First, Rusha Chowdhury and Srijana Naskar from Jadavpur University presented a paper on Stranger Things and the notion of the demogorgon as the embodiment of a world tired of the failure to address climate change. The paper drew alluded to the research establishments in Stranger Things as a legacy of politics and attitudes of the cold war. I found this particularly intriguing given how – as Oreskes and Conway point out in Merchants of Doubt – so many of the off-specialism climate denying scientists of the late twentieth century were brought up in the Cold War political tension of capitalism vs communism. Those scientists opposition to climate action originates in a perception that – in its critique of capitalism – climate activism was simply an extension of the Cold War by other means. That division on tribalist lines was further emphasised when the speakers pointed out how activism was accused of satanism and unchristian attitudes, before concluding with a quote of Scott Clarke from series one episode five, “Science is neat, but I’m afraid it’s not very forgiving.”

Cynthia Zhang from California University spoke next with her paper on Making Kin – Princess Mononoke as cli-fi fantasy. Cynthia noted that, while climate change is an issue often addressed through science fiction, it is a theme that fantasy can also productively address. The fantastic tale of Prince Ashitaka and his encounters with both forest gods and the matriarch of an extractive mining town challenged notions of human mastery of nature and offered a ecological fable to address the non-human impacts of our environmental stories. In so doing Princess Mononoke could be viewed as an exemplar of new materialism with matter seen as agential rather than inanimate.

My own paper Climate Change Crime: Transforming perspectives on the climate crisis through guilt, anger and mystery considered how the theme of climate change has transformed literature, permeating every genre – in particular crime fiction. I considered Rebecca Dimick’s continuum of guilt and how narratives such as Jon Raymond’s Denial challenge binary depictions of guilt and innocence. Saci Lloyd’s Carbon Diaries 2015 and Ross Clark’s The Denial both note the sense of loss and grief that comes with the end of the fossil fuel age and cli-fi narratives need to acknowledge this. Empathy is not the only emotion literature can stimulate and transformative cli-fi stories also stimulate hope and anger while modelling effective collective action to counter fossil fuel industry propaganda.

My own paper Climate Change Crime: Transforming perspectives on the climate crisis through guilt, anger and mystery considered how the theme of climate change has transformed literature, permeating every genre – in particular crime fiction. I considered Rebecca Dimick’s continuum of guilt and how narratives such as Jon Raymond’s Denial challenge binary depictions of guilt and innocence. Saci Lloyd’s Carbon Diaries 2015 and Ross Clark’s The Denial both note the sense of loss and grief that comes with the end of the fossil fuel age and cli-fi narratives need to acknowledge this. Empathy is not the only emotion literature can stimulate and transformative cli-fi stories also stimulate hope and anger while modelling effective collective action to counter fossil fuel industry propaganda.

The first day concluded with a key-note address by Roz Kaveney Against Intention – Random and aleatoric elements in the creation of Rhapsody of Blood. Roz led us through the process of crafting her five volume two-thirds of a million word tale of Mara the immortal huntress travelling through time and the lovers Emma and Caroline that even death cannot part. Roz read from her works and spoke entertainingly about the long gestation process for the novels – which had benefitted in part from an excursion into writing fan-fiction (so don’t knock fan-fic). Roz’s talk title challenged the notion of author as authority and indeed alluded to the fallacy of originalism in readings of the American constitution; that process by which interpretations are made of issues the constitution’s authors could never have anticipated and for which the process of constitutional amendments was surely invented!

End of Day One Group Photo

Roz did not see books so much as in Barthes’ Death of the Author – with novels drifting away from authorial intention on a tide of reader interpretation – rather than books as “thick texts.” That palimpsest of influences is clear in how Roz’s appreciation of History allowed her to revise and thread characters and events around Mara’s story. Fascinatingly, Roz revealed that original recordings of historical voices are available on Youtube – for example Florence Nightingale recorded by Edison in 1890 and in such ways the past can span the centuries to speak to and inspire the present.

The formal conference proceedings were followed by a CRSF innovation with David Tierney comparing an open-mike event where attendees (including David himself) shared examples of their non-fiction writing.

The formal conference proceedings were followed by a CRSF innovation with David Tierney comparing an open-mike event where attendees (including David himself) shared examples of their non-fiction writing.

Other readings included Lucy Nield’s wonderfully comic story Input-Output about alien observers making a cyclic return to Earth in the midst of Covid lockdown and finding it was not just the pandemic that had wrought great changes from their last Victorian era visitation.

Jordan Castelles delivered a haunting short story that morphed from an account of an enquiry into an unfinished magazine serialisation into a performance piece that made participant witnesses of the audience!

Jordan Castelles delivered a haunting short story that morphed from an account of an enquiry into an unfinished magazine serialisation into a performance piece that made participant witnesses of the audience!

And the day’s events concluded with Roz reading one of her poems and then an adjournment to the Cambridge pub!

Day Two – 30th June

Day Two for me began with a panel on Bodies. The vagaries of Zoom conferencing did create some issues which the team of chairs and technical support managed effectively with a bit of shuffling of the order of online and in person speakers. Dr Samantha Hind from Sheffield spoke about Speculative Flesh Ecologies exploring different forms of ‘consumables’ under the broad umbrella of ‘flesh.’ Drawing on her doctoral thesis she extended the notion of ‘thing flesh’ that she had addressed in her presentation last year to include animals, plants, cultured flesh and humans and a sample of books that interrogated the ethical thinking behind the consumption of each form of flesh.

Day Two for me began with a panel on Bodies. The vagaries of Zoom conferencing did create some issues which the team of chairs and technical support managed effectively with a bit of shuffling of the order of online and in person speakers. Dr Samantha Hind from Sheffield spoke about Speculative Flesh Ecologies exploring different forms of ‘consumables’ under the broad umbrella of ‘flesh.’ Drawing on her doctoral thesis she extended the notion of ‘thing flesh’ that she had addressed in her presentation last year to include animals, plants, cultured flesh and humans and a sample of books that interrogated the ethical thinking behind the consumption of each form of flesh.

Leah Collins then considered Body Modification drawing on the original cyborg of Frankenstein’s monster and considering that development in Ishiguro’s Never Let me Go and Atwood’s Oryx and Crake. Ishiguro’s tale of human clones bred, fed and educated as potential organ donors for the ultra-wealthy epitomised the ultimate ‘corporate colonialism of the high tech body’ with people envisaged as an extractive resource and only the rich are deemed – or can afford to be – ‘fully human.’ As Leah pointed out, the clones of Never let Me Go were complacent in their own commodification, while the bio-products of Oryx and Crake made the crakers into a kind of superior post human. However, unlike the ousters of Dan Simmons Hyperion Falls, these were not morally elevated beings – scientific dominance was not synonymous with moral credence and both books presented modified bodies as exemplars of unregulated modes of capitalism.

Dr James Gillham then presented on Stapeldon’s Humpty: a nasty piece of work looking at how Olaf Stapledon’s writings exploring spontaneously generated alternate forms of humans as though nature were striving to improve on its first experimental humanity, and in the process held up a mirror to show us ourselves in grotesque form.

With a certain kind of logic I went from a panel on Bodies to one on Death Positivity which opened with Scarlette-Electra LeBlanc presenting on one of Mary Shelley’s later works The Last Man. This early work of apocalyptic fiction, with its notion of a 21st century plague, not only emphasises Shelley’s foundational status in generating what have become sci-fi tropes, but also has a fresh contemporary relevance as Covid’s ripples continue to echo around the world. However, Scarlette-Electra’s presentation looked at the book’s potential purpose as a therapeutic and almost autobiographical exploration of loss and grief in the life of a woman who had lost children, her husband and their friend all in a few short years. In different forms the person of Percy Bysshe Sheele appears within the text and can be lost and mourned in different ways.

Hollie Willis followed this up with a presentation on Tolkien’s middle earth and the different ways in which the transformation of corpses can be unpacked. Hollie touched on the dead marshes as an allegory for Tolkien’s experience of corpse filled shell holes in the battle of the Somme. The sheer numbers of the dead led to a de-individualisation, imbuing the corpses with a collective identity and (in the Dead Marshes more than the Somme) an incorporeality where the spirit remained as the corpse decayed. Hollie also considered the contrasting deaths of Feanor subjected to post-mortem self-cremation due to the fire of his spirit leaving his body, and Saruman – his incorporeal presence scattered by the wind, denied not just dignity in death, but also any chance of resurrection or redemption. It is revealing that the Catholic church – in believing intact bodies were needed for the day of resurrection – did not accept cremation as burial rite until 1963, which context must have influenced the devoutly catholic Tolkien’s thinking.

Hollie Willis followed this up with a presentation on Tolkien’s middle earth and the different ways in which the transformation of corpses can be unpacked. Hollie touched on the dead marshes as an allegory for Tolkien’s experience of corpse filled shell holes in the battle of the Somme. The sheer numbers of the dead led to a de-individualisation, imbuing the corpses with a collective identity and (in the Dead Marshes more than the Somme) an incorporeality where the spirit remained as the corpse decayed. Hollie also considered the contrasting deaths of Feanor subjected to post-mortem self-cremation due to the fire of his spirit leaving his body, and Saruman – his incorporeal presence scattered by the wind, denied not just dignity in death, but also any chance of resurrection or redemption. It is revealing that the Catholic church – in believing intact bodies were needed for the day of resurrection – did not accept cremation as burial rite until 1963, which context must have influenced the devoutly catholic Tolkien’s thinking.

Then Julia A. Empey presented on depictions of Mind Uploading in science fiction as a means of death denial. While narratives such as Netflix’s Altered Carbon and use uploading as a form of resurrection or immortality, Julia’s paper considered how far they emphasised a cartesian dualism that sees mind and body as separate but conjoined entities. The pursuit of immortality and the sharing of a carrier mind by a host body/vessel have been enduring themes in speculative fiction from Wyndham’s Chocky to the comedy show Upload. It was interesting to hear Julia’s assertion from these “anti-death” imaginings that death is ”not in opposition to life, but existing a flat continuum entwined with it.” It is also curious how uploading – as opposed to mind sharing – implies a copy being made, a mind-clone which lives on, while the original dies – which was explored in questions and coffee discussions.

After a generous buffet lunch, my final panel of paper presentations was on the interesting exhortation to Make it Weird, Andras Fodor opened the session with an examination of Contemporary Scandinavian New Weird Realities. It made for an interesting departure from the broadly anglophone texts that had prevailed in most papers. It also meant that relatively few attendees were familiar with the Swedish authors Andras cited. Andras focussed on three Scandinavian new weird novels where the consumption of plants created a Kafkaesque bending of reality in utopian-dystopian settings. Spaces become alarmingly defamiliarised and estranged, but Andras’ argument is that these depictions of plants offer a route to a more hopeful and more-than-human future.

After a generous buffet lunch, my final panel of paper presentations was on the interesting exhortation to Make it Weird, Andras Fodor opened the session with an examination of Contemporary Scandinavian New Weird Realities. It made for an interesting departure from the broadly anglophone texts that had prevailed in most papers. It also meant that relatively few attendees were familiar with the Swedish authors Andras cited. Andras focussed on three Scandinavian new weird novels where the consumption of plants created a Kafkaesque bending of reality in utopian-dystopian settings. Spaces become alarmingly defamiliarised and estranged, but Andras’ argument is that these depictions of plants offer a route to a more hopeful and more-than-human future.

Then the Fantasy-Hive’s own Jonathan Thornton delivered a paper on Hive Minds in SFF (of course he would!). Jonathan considered the aliens in Ender’s game, generating a memorable quote, “The alien buggers… that’s their actual name” and exploring how the interrelatedness of the individual organisms within hive or swarm species created a kind of immortality. Jonathan considered the political dimensions of this – the hive being a metaphor for communism where rugged individuality is the preserve of heroic American capitalism. It is a fascinating dichotomy. On the one hand there are notions of separateness, individuality, competing against others, seeking personal immortality (eg through uploads) and extractive practices from an external nature. On the other hand is the connectedness of a hive organism where the individual organisms collaborate to achieve a collective (species) immortality where boundaries between organism and nature are more blurred. I found resonances with my own work and particularly the need for a collective and connected response to the climate crisis that does not depend on individual heroes (protagonism) or techno-fixes. Jonathan concluded that organic hives within science fiction enable humanity to confront binary oppositions of civilisation and nature.

Then the Fantasy-Hive’s own Jonathan Thornton delivered a paper on Hive Minds in SFF (of course he would!). Jonathan considered the aliens in Ender’s game, generating a memorable quote, “The alien buggers… that’s their actual name” and exploring how the interrelatedness of the individual organisms within hive or swarm species created a kind of immortality. Jonathan considered the political dimensions of this – the hive being a metaphor for communism where rugged individuality is the preserve of heroic American capitalism. It is a fascinating dichotomy. On the one hand there are notions of separateness, individuality, competing against others, seeking personal immortality (eg through uploads) and extractive practices from an external nature. On the other hand is the connectedness of a hive organism where the individual organisms collaborate to achieve a collective (species) immortality where boundaries between organism and nature are more blurred. I found resonances with my own work and particularly the need for a collective and connected response to the climate crisis that does not depend on individual heroes (protagonism) or techno-fixes. Jonathan concluded that organic hives within science fiction enable humanity to confront binary oppositions of civilisation and nature.

Then Frankie Hallam, delivering on the Make it Weird imperative presented a paper entitled Weird, Wet and Oscene. The paper examined how sea creature imaginaries could facilitate genderqueer bodies through bodily transformation. Through a focus on Lucile Hadžihalilović’s film Evolution and Rita Indiana’s novel Tentacle Frankie explored how the sea provided both context and impetus for personal and societal transformations. Tentacle’s vision of a time traveller the maid Alcide rebirthing herself as man in the 1990s Caribbean on a mission to save humanity presented a narrative of estrangement from normative sexuality. The text draws on established biology of male seahorse gestation and starfish regeneration to highlight the possibilities in transgender and genderqueer futurity. This enables it to challenge fears and prejudices that the category of human is literally embodied in a corporeal stereotypes.

Leading up to the final Key-note, Jonathan Thornton chaired an author round table looking at Speculative Transformations through the work and insights of authors E.J.Swift, Paul McAuley, Tlotlo Tsamaase and Ryka Aoki. A lively discussion and Q&A session ensued with a focus on how to bring in hope when the real world is still quite bleak. Ryka queried whether all change was – or had to be technological – or could we “elevate ourselves at home.” As E.J.Swift pointed out narratives should acknowledge what has happened without sinking into despair. Ryka concurred but insisted her readers should work for their ‘hope’ saying “hope should be earned not treacly.” Paul echoed that sense of a reader actively engaging and working with the text and that beyond author and characters “there is another person in the book.” Ultimately, as E.J.Swift summarised, “you want people to care but not despair.”

Leading up to the final Key-note, Jonathan Thornton chaired an author round table looking at Speculative Transformations through the work and insights of authors E.J.Swift, Paul McAuley, Tlotlo Tsamaase and Ryka Aoki. A lively discussion and Q&A session ensued with a focus on how to bring in hope when the real world is still quite bleak. Ryka queried whether all change was – or had to be technological – or could we “elevate ourselves at home.” As E.J.Swift pointed out narratives should acknowledge what has happened without sinking into despair. Ryka concurred but insisted her readers should work for their ‘hope’ saying “hope should be earned not treacly.” Paul echoed that sense of a reader actively engaging and working with the text and that beyond author and characters “there is another person in the book.” Ultimately, as E.J.Swift summarised, “you want people to care but not despair.”

“Hope should be earned, not treacly.” Ryka Aoki

The concluding Keynote, somewhat fittingly, was delivered by Dr Chris Pak from Swansea University who had launched the CRSF conference as a PhD student at Liverpool University in 2011. His familiarity and fondness for the event and the city was clear throughout the conference and in his knowledge of great local knowledge places to eat. Roz Kaveney described the Hot and sour soup (I think I have remembered the right flavour) at Chris’s recommendation of The Big Bowl Noodle Bar as “the best” she had ever tasted.

Wearing a suitable “Occupy Mars” T-shirt, Chris delivered a key-note on Science fiction’s ability to contribute to debates about terraforming, including ideas about aerosol particle injection into the atmosphere to counter global warming by increasing the Earth’s albedo/reflectivity. Chris;s work was particularly interesting given Amitav Ghosh’s harangue to authors to address climate change because “the imagining of possibilities is not, after all, the job of politicians and bureaucrat.” Chris described his work in an interdisciplinary project looking at what story-telling and story-listening can bring to climate crisis strategising. The expression, and resolution, of eco-anxiety in terraforming narratives has relevance to approaches to climate change where emotions already run high without the propaganda manipulation of the fossil fuel industry. While Chris acknowledged the project involved working with constraints of avoiding overt politisisation, it is intriguing to see story telling being enlisted in this work. As a species we have always learned best through stories, be they fables or myths. The climate crisis is – as I have asserted elsewhere – a crisis of communication far more than one of science, technology or even politics. The crisis needs its stories and its story tellers.

Wearing a suitable “Occupy Mars” T-shirt, Chris delivered a key-note on Science fiction’s ability to contribute to debates about terraforming, including ideas about aerosol particle injection into the atmosphere to counter global warming by increasing the Earth’s albedo/reflectivity. Chris;s work was particularly interesting given Amitav Ghosh’s harangue to authors to address climate change because “the imagining of possibilities is not, after all, the job of politicians and bureaucrat.” Chris described his work in an interdisciplinary project looking at what story-telling and story-listening can bring to climate crisis strategising. The expression, and resolution, of eco-anxiety in terraforming narratives has relevance to approaches to climate change where emotions already run high without the propaganda manipulation of the fossil fuel industry. While Chris acknowledged the project involved working with constraints of avoiding overt politisisation, it is intriguing to see story telling being enlisted in this work. As a species we have always learned best through stories, be they fables or myths. The climate crisis is – as I have asserted elsewhere – a crisis of communication far more than one of science, technology or even politics. The crisis needs its stories and its story tellers.

Following Chris’s intriguing keynote there only remained the expression of thanks to the team, from Lucy. This was followed by thanks from the team to Lucy on the occasion of her stepping back from active involvement in the organisation of CRSF. As Jonathan put it, she is the “Russell T Davies” of CRSF for having breathed new life into a much appreciated but somewhat dormant speculative fiction event.

Following Chris’s intriguing keynote there only remained the expression of thanks to the team, from Lucy. This was followed by thanks from the team to Lucy on the occasion of her stepping back from active involvement in the organisation of CRSF. As Jonathan put it, she is the “Russell T Davies” of CRSF for having breathed new life into a much appreciated but somewhat dormant speculative fiction event.

End of Day Two Photograph

We then adjourned once more to the Cambridge for much conviviality aided by alcohol, CRSF funded chip butties, and good company. Challenges were issued as to what paper titles or topics could prove most shockingly enticing next year and apparently some hardy souls braved a late night kebab shop. However, CRSF will return with much the same management in 2024, which should give everybody just enough time to recover from post-conference hangovers – and more importantly work through the labyrinthine process of getting the necessary university funded travel grants!