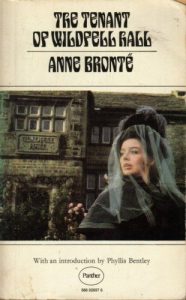

THE TENANT OF WILDFELL HALL by Anne Brontë (BOOK REVIEW)

“I am so determined to love him – so intensely anxious to excuse his errors, that I am continually dwelling upon them, and labouring to extenuate the loosest of his principles, and the worst of his practices, till I am familiarized with vice, and almost a partaker in his sins. Things that formerly shocked and disgusted me, now seem only natural. I know them to be wrong, because reason and God’s Word declare them to be so; but I am gradually losing that instinctive horror and repulsion which were given me by nature…”

Out of all three of the iconic gothic novels written by the Brontë sisters – Emily’s Wuthering Heights (1847), Charlotte’s Jane Eyre (1847) and Anne’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848) – Anne’s novel is the least well known and frequently read. This is a great shame, as The Tenant of Wildfell Hall is a gothic classic of the first water, a great work of the Brontë imagination that easily stands as equal with her sister’s better-known works. The novel may lack the supernatural intensity of Wuthering Heights, but it nevertheless is a work of barely-contained passion and a vivid struggle against the forces of damnation. It’s also a powerfully feminist text, railing against the plight of women in the 19th century and portraying in vivid and upsetting detail a strong woman who finds herself trapped in an abusive marriage.

Gilbert Markham is a gentleman farmer in the countryside, who finds his mundane village life disrupted by the coming of a mysterious widow, Helen Graham, who has moved into the crumbling ruins of Wildfell Hall with her young son Arthur. At first, like the rest of the villagers, Gilbert finds Helen cold and stand-offish, but as the two get to know each other his antipathy is replaced with respect and admiration for Helen’s intelligence and integrity, whilst Helen is drawn to his charm and honesty. Soon Gilbert finds himself defending Helen’s reputation against the malicious but troubling rumours that circulate about her amongst the local gossips. But just as Gilbert is ready to declare his feelings for Helen, he overhears an exchange which appears to prove the worst about Helen’s character. Confronting her, she provides him with her diaries, which reveal that her unusual situation is not the result of any fault of her own, but her husband Arthur Huntingdon’s descent into abusive drunkenness.

Gilbert Markham is a gentleman farmer in the countryside, who finds his mundane village life disrupted by the coming of a mysterious widow, Helen Graham, who has moved into the crumbling ruins of Wildfell Hall with her young son Arthur. At first, like the rest of the villagers, Gilbert finds Helen cold and stand-offish, but as the two get to know each other his antipathy is replaced with respect and admiration for Helen’s intelligence and integrity, whilst Helen is drawn to his charm and honesty. Soon Gilbert finds himself defending Helen’s reputation against the malicious but troubling rumours that circulate about her amongst the local gossips. But just as Gilbert is ready to declare his feelings for Helen, he overhears an exchange which appears to prove the worst about Helen’s character. Confronting her, she provides him with her diaries, which reveal that her unusual situation is not the result of any fault of her own, but her husband Arthur Huntingdon’s descent into abusive drunkenness.

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall is an unusual gothic novel in a number of ways. The crumbling ruins of Wildfell Hall, as drear and as imposing as any gothic mansion, may instill dread in Gilbert, but for Helen it is a miraculous safe haven, a place where she can bring up her son free of the poisonous influence of his father. It stands in stark contrast to Grassdale, Arthur Huntingdon’s family home, a place of luxury transformed into an oppressive prison thanks to his horrendous behaviour. The Tenant of Wildfell Hall has no supernatural presence; it doesn’t need one. The horror of living with an abusive asshole is terrifying enough. The novel is a thoughtful and disturbing portrait of how anyone can wind up in an abusive relationship. When Helen first meets Arthur, her aunt is trying to convince her to marry a condescending bore of a man, who is much older than her but is rich. Arthur’s easy-going charm is a refreshing change for the young woman, who quickly finds herself falling for him. In this initial stage of infatuation, she perceives some red flags in Arthur’s behaviour and his attitude towards his friends, but is quick to find excuses for them, as might any young person in the first flush of romantic love.

Helen agrees to marry Arthur, and has a son with him, and it is then that his true colours are revealed, and her life quickly degenerates into a living hell. Through her heartbreaking diary entries, we see Helen’s heroic resolve as she struggles to love and support a man who is rapidly turning into a complete monster. Arthur, like Anne’s brother Branwell, has a serious problem with alcoholism, and when he drinks he really becomes an asshole. Helen is forced to endure his endless drinking sessions with his horrible friends, his lengthy unexplained absences, his ungrateful and abusive treatment of her while she nurses him back to health and attempts to save his soul. Her kindness and endurance is paid back in more abuse, and in Arthur cheating on her. Eventually, despite her commitment to her marriage vows, and to living with the consequences of her own mistakes, she is forced to escape to her estranged brother’s crumbling property Wildfell Hall in order to save her young son Arthur from Arthur senior’s poisonous influence.

These sequences are the most powerful and disturbing parts of the novel. Anne expertly conveys the claustrophobia and dread of living with an abusive partner, the exhaustion and profound sorrow of watching someone you love descend into self-destruction while you are unable to save them. Here all the tropes of gothic fiction are deployed to show the horror of living with an abusive spouse, especially in the days when getting divorced from them without their permission was impossible and escaping them would mean that rumours of one’s impropriety would follow one wherever one went. Helen is a remarkable character, her strength and resilience and her commitment to her principles truly heroic, the novel showing her strength of character in the face of her untenable situation rather than painting her as a helpless victim. The novel is rightly furious at the lot of women in the 19th century, where so much of their happiness, safety and security is taken away from them in a patriarchal system and you basically just have to trust that your husband won’t be a jerk, with no recourse if he is. The Tenant of Wildfell Hall has much to say about abusive relationships, and those who suffer them and survive them, that is still powerfully and upsettingly relevant in the present day.

Fortunately, the narrative structure allows Anne to mete out the kind of karmic retribution and resolution that is frequently denied people in real life. Arthur comes to a sticky end, leaving Helen and Gilbert free to declare their love to each other and move on with their lives, though this happy ending is far from easily earned by either of them. Arthur’s descent into a hell of his own making is as chilling and disturbing as anything else in the book, and Helen’s happy and healthy relationship with Gilbert and the clearing of her reputation are wonderfully cathartic. The Tenant of Wildfell Hall deserves to stand with Anne’s siblings’ more famous works, as a powerful and disturbing work of gothic fiction and psychological horror. As with Emily, Anne’s early death robbed us of more work from her brilliant mind, but we can be thankful that she was able to produce this work of genius in her lifetime.