SPECULATIVE FICTION’S FONDNESS FOR SECOND CHANCES – Article by TO Munro

The first assembly that I did in school was about Schrödinger’s Cat. This virtual experiment starts with the idea of a cat in a box with a poison bottle. A mechanism is arranged so the bottle has a 50% chance of being broken by a ‘quantum event’ of a single atom decaying. The physics suggests that the atom is simultaneously decayed and undecayed and – by extension – the cat is simultaneously both alive and dead right up until the moment the box is opened and the results of the experiment are ‘observed.’

However, it wasn’t the physicist’s insight into the apparent absurdity of quantum mechanics that inspired my assembly so much as the potential for multiple worlds that is one possible implication of his thought experiment. In this interpretation, at the moment where the cat is observed, the universe splits into two alternative versions one with a dead cat and one with a live cat. (There is even a suggestion that the optimism – or pessimism of the observer might affect the outcome.)

However, it wasn’t the physicist’s insight into the apparent absurdity of quantum mechanics that inspired my assembly so much as the potential for multiple worlds that is one possible implication of his thought experiment. In this interpretation, at the moment where the cat is observed, the universe splits into two alternative versions one with a dead cat and one with a live cat. (There is even a suggestion that the optimism – or pessimism of the observer might affect the outcome.)

This idea of different time-lines, second chances and alternative outcomes is a fascinating one – the what-if’s of “could we go back and redo an event?”

The chance to undo any or all of the many faux-pas littering our lives is alluring. Maybe it’s just me, but old ill-chosen comments or actions still taunt me, surfacing unbidden from the depths of my memory. For example that time – when trying to impress an interview candidate at the ‘meet the school staff’ event – I told my future headteacher that the remarkable thing about our multi-building site was how “All the doors were on the outside.”

Some of those instances go beyond momentary faux-pas into more grievous mistakes. I take it as a sign that I’m not a sociopath that I find myself more haunted by the times I’ve hurt people than the times I’ve been hurt. Our teenage years and the difficult early twenties are times where apparently our brains are still staggering through a fog of callow self-absorption towards considerate adult maturity – and there are a fair few situations I could have handled with more grace and empathy.

But of course the big appeal of the re-dos – either by creating or slipping into a parallel universe – is the chance to pursue different life chances to un-miss those missed opportunities. “What if I hadn’t knocked that glass of water over at that job interview?” or “What if I’d remembered to shut that door?” Could those butterfly-wing moments have led to just the merest blip in our careers or romantic relationships, or would they have carved out a whole new life path for us?

The fascination of exploring those many ‘roads not travelled’ is one that attracts speculative fiction authors like moths drawn to a flame, and there are quite a few books and films that play with the idea of being able to undo a mistake (or to make a different one). In this post I’ll take a look at a few of them.

The What Ifs

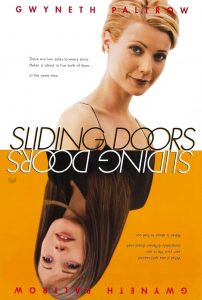

The film Sliding Doors (1998) – took one pivotal moment in the life of Helen Quilley. Did she just manage to make that tube train, or did the slightest chance delay mean the eponymous sliding doors slid shut before she could board? The film then pursued how her two parallel lives played out. There was the one where – having missed the train – Helen returned home to discover her boyfriend cheating on her and set out on a new life. A new-life-new-me hair cut helped the viewer to distinguish this timeline from the other one where she beat the sliding doors to board the train. In this interwoven version of the present, she carried on her old life – initially at least – unaware of the boyfriend’s infidelity.

The film Sliding Doors (1998) – took one pivotal moment in the life of Helen Quilley. Did she just manage to make that tube train, or did the slightest chance delay mean the eponymous sliding doors slid shut before she could board? The film then pursued how her two parallel lives played out. There was the one where – having missed the train – Helen returned home to discover her boyfriend cheating on her and set out on a new life. A new-life-new-me hair cut helped the viewer to distinguish this timeline from the other one where she beat the sliding doors to board the train. In this interwoven version of the present, she carried on her old life – initially at least – unaware of the boyfriend’s infidelity.

Matt Haig’s The Midnight Library (which I reviewed for the Hive here) picked up on another more obviously critical moment in the life of Nora Seed. As the thirty-five-year-old protagonist hovers on the brink of a potentially successful suicide she is transported to ‘The Midnight Library’ in that liminal space between life and death. The library is stocked with the books of all the other lives she might have led if she had taken different choices – a catalogue, if you like, of all the ‘sliding doors’ moments in her life. She has the chance to drop into any life she plucks from the shelf and experience the present time for the other versions of herself that she could have been. She even has the chance to decide if she wants to stay in that alternative life and move forward from that point. However, she arrives always very much ‘in media res’. Like Quantum Leap’s protagonist Sam ‘Oh Boy’ Beckett, she enters each life with no knowledge of what has transpired in the years between that long ago ‘sliding doors’ moment and the present time. On each occasion it takes a bit of pocket checking and frantic self-googling to work out what kind of person ‘the road not travelled’ had made of her.

Sliding doors was a fun play on the what-if moments that can cause huge shifts in one’s life. The jobs we didn’t get, the signs we missed. However – like the very strange Roger Moore film The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970) – there comes a point where the narrative demands the twin timelines must resolve themselves and Schrodinger’s wave equation collapses to a single counter-intuitive outcome in which only one life can go forward.

Sliding doors was a fun play on the what-if moments that can cause huge shifts in one’s life. The jobs we didn’t get, the signs we missed. However – like the very strange Roger Moore film The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970) – there comes a point where the narrative demands the twin timelines must resolve themselves and Schrodinger’s wave equation collapses to a single counter-intuitive outcome in which only one life can go forward.

In The Midnight Library no matter how many lives Nora explores, there can also only be one that the suicidal young woman will settle on. The point of the book is perhaps, that all the other lives you might have lived are just as fraught with triumph and disaster as the one you took. Different in nature maybe, but not in substance. While A Christmas Carol‘s Scrooge didn’t get quite the range of alternatives that Nora Seed is shown, like the old miser, Nora’s journey ultimately doesn’t change who she chooses to be, it makes her change what she does about it.

The Re-dos

The big theme in The Midnight Library is you can’t covet just one part of another lifestyle. Whether it be you own ‘road not taken’, or the promotion given to a work rival or the wealth and fame of a celebrity idol, you would have to accept every element of that alternative lifestyle warts and all.

Furthermore, given that we are fashioned from our experiences and memories, there is a kind of suicidal ideation in hankering after one or other ‘road less travelled.’ Essentially it is wishing your present self out of existence and that another person than the ‘you of now’ had lived a different life – on the assumption that you can carry no memories of your alternate timelines into the one you eventually settle on.

One of the earliest alternative timeline stories predates even Schrodinger and his imaginary feline. Ernest Swinton’s brief but effective Boer War military parable The Defence of Duffer’s Drift takes a young army officer through six iterations of an unsuccessful defence of a particular river crossing. Like Dickens’ Scrooge, these visions come to him in a succession of dreams. He wakes from each one with only a vague sense of unease and one additional simple lesson that the latest military failure has given him to apply to the next attempt – culminating in a successful military action.

One of the earliest alternative timeline stories predates even Schrodinger and his imaginary feline. Ernest Swinton’s brief but effective Boer War military parable The Defence of Duffer’s Drift takes a young army officer through six iterations of an unsuccessful defence of a particular river crossing. Like Dickens’ Scrooge, these visions come to him in a succession of dreams. He wakes from each one with only a vague sense of unease and one additional simple lesson that the latest military failure has given him to apply to the next attempt – culminating in a successful military action.

In Kate Atkinson’s Life after Life, the protagonist Ursula Todd has a similar vague awareness of other lives and decisions, though in this case the decisions lead not into humiliating military defeat but simply an untimely death. Then the entire life is lived out again and Ursula comes to the new situation only vaguely armed as to how best to survive it. Like The Defence of Duffer’s Drift some dilemmas are more obdurate than others. It takes Ursula several fatal attempts to navigate the perils of the influenza epidemic of 1919 and emerge into the relative safety of the 1920s. And the tottering gable wall of a bombed-out house in the 1940s claims quite a few of Ursula’s limitless supplies of lives. (Oh, that Schrodinger’s cat should be so lucky!) Overall, Ursula’s life feels like a computer game in which the protagonist is constantly respawning right back at the moment of birth, and fighting several ‘boss level’ adversaries on her way to the end goal of what… old age?

While The Defence of Duffer’s Drift is fable-ously instructive, Life After Life feels more like an insight into the fragility of human existence, the moments when it was only a fortuitously placed shrubbery that stopped your sleeping six-year-old body from sliding out under a tent fly sheet and over a precipice (no? just me then?). While one critic felt it was about the avoidability – rather than inevitability – of the second world war, other opinions differed. Life after Life is a fun read, and an interesting insight into the-might-have-beens, but perhaps it is also about the struggle between author and protagonist with Ursula finding ways to evade the fates that Atkinson has picked for her. Would that some of G.R.R.Martin’s characters had had that opportunity!

While The Defence of Duffer’s Drift is fable-ously instructive, Life After Life feels more like an insight into the fragility of human existence, the moments when it was only a fortuitously placed shrubbery that stopped your sleeping six-year-old body from sliding out under a tent fly sheet and over a precipice (no? just me then?). While one critic felt it was about the avoidability – rather than inevitability – of the second world war, other opinions differed. Life after Life is a fun read, and an interesting insight into the-might-have-beens, but perhaps it is also about the struggle between author and protagonist with Ursula finding ways to evade the fates that Atkinson has picked for her. Would that some of G.R.R.Martin’s characters had had that opportunity!

The Multiple lives

Within Ursula’s tale there are some timelines where she travels to Europe in the 1920s and 30s – a slight curve ball in the general Anglo-centric narrative. There Atkinson indulges the popular thought experiment “let’s kill Hitler” with Ursula as assassin. Disappointingly, Ursula – in immediately falling victim to the proto-tyrant’s bodyguards – can give us no insight as to how a Hitler-less world would have played out.

However, it does leave one curious as to how the many other threads of Ursula’s life would play out after her death – how many worlds are spawned. Authors like to leave readers wondering ‘what happens next’ and Life after Life gives us a lot of ‘nexts’ to contemplate.

In other stories of multiple lives though, the protagonist – in remembering every detail from one version of their life to the next – has much more potential agency to tweak the course of history.

The eponymous hero of Claire North’s The First Fifteen Lives of Harry August relives whole lives, not just a single day. Like Kate Addison’s Ursula each death just sends him back to be reincarnated at birth and to – somewhat traumatically – come into the inheritance of his memory of his entire previous lives around the age of four or so. Initially mistaken for a madman Harry is guided in his new multiple existences by other people with the same gift the Ouroboran who have their own association the Cronus Club. Given the Ouroborans’ potential to use the knowledge acquired in previous lives to change the history of the world for their present life, the Cronus Club endeavours to enforce the utmost discretion on its members, expecting that the ‘gift’ is used only to claim comfort rather than attain world domination.

The eponymous hero of Claire North’s The First Fifteen Lives of Harry August relives whole lives, not just a single day. Like Kate Addison’s Ursula each death just sends him back to be reincarnated at birth and to – somewhat traumatically – come into the inheritance of his memory of his entire previous lives around the age of four or so. Initially mistaken for a madman Harry is guided in his new multiple existences by other people with the same gift the Ouroboran who have their own association the Cronus Club. Given the Ouroborans’ potential to use the knowledge acquired in previous lives to change the history of the world for their present life, the Cronus Club endeavours to enforce the utmost discretion on its members, expecting that the ‘gift’ is used only to claim comfort rather than attain world domination.

The fact that Harry is not alone in his ‘talent’ – and the mystery/thriller element that North throws into the plot – implies the existence of a dizzying array of multiple worlds. Harry’s Ouroboran existence involves him (or perhaps just his accumulated memories) moving through complicated layers of different timelines (and universes) all overlaid on each other in some nth dimension. Like the mathematicians’ beloved imaginary numbers there are imaginary times (iTimes?!) or alternative timelines, that Harry’s successive lives descend through. Curiously, in his Library trilogy, Mark Lawrence makes exactly that use of alternative timelines for his characters to navigate in what become increasingly entangled versions of now.

In the case of Claire North’s Harry these other universes are also inhabited by different versions of us ordinary non-Ouroboran – possibly at the mercy of a fickle Ouroboran. However, there is still a sense of some form of Time’s arrow (iTime’s arrow?!) moving in one direction only. It is clear from the book’s very title, that Harry’s lives are sequential and he cannot go back to change what happened in a previous life. He can only live his current life in a different way armed with the memories of previous lives.

In the case of Claire North’s Harry these other universes are also inhabited by different versions of us ordinary non-Ouroboran – possibly at the mercy of a fickle Ouroboran. However, there is still a sense of some form of Time’s arrow (iTime’s arrow?!) moving in one direction only. It is clear from the book’s very title, that Harry’s lives are sequential and he cannot go back to change what happened in a previous life. He can only live his current life in a different way armed with the memories of previous lives.

In Ground Hog Day (1993) cynical weather reporter Phil finds his life is glitching like the scratched record at the end of Brighton Rock. Rather than resetting to the very start each time, he relives numerous versions of the same snowbound day going through several stages; disbelief, frustration, exploitation (stealing money and charming his way into women’s beds), desperation (with several pointless suicide attempts – he just wakes up back at the start of the day), and eventual mellowing. Armed with the memories of all the days he has lived he acquires a grace towards and appreciation of the smalltown setting in which he is trapped and begins to serve it and enjoy it, rather than berate and exploit it. As with all good stories – even though the day may not change – the character does.

Changing the past

In both The First Fifteen Lives of Harry August and Groundhog Day a key theme is that the world is being changed through the opportunity the protagonists (or Harry’s fellow Ouroboran) have to live different lives. Other stories are more tightly focused on how the protagonist uses or abuses the power in their relationships.

In the film About Time (2013) Tim Lake discovers from his father that the adult males in his family have the power to jump back any ‘distance’ on their own timeline, diving shallowly or deeply into their own past. This gives them the power to relive any key ‘sliding doors’ moments they choose and do so as many times as they like using their knowledge of the future to do things differently, maybe do things better. But this is not just about second chances – it is time travel. Tim, having dabbled in changing what he did years ago, can return to the present and see the outrun of his meddling. However, with some shorter jumps of mere minutes he appears to just live his way back into the present.

In the film About Time (2013) Tim Lake discovers from his father that the adult males in his family have the power to jump back any ‘distance’ on their own timeline, diving shallowly or deeply into their own past. This gives them the power to relive any key ‘sliding doors’ moments they choose and do so as many times as they like using their knowledge of the future to do things differently, maybe do things better. But this is not just about second chances – it is time travel. Tim, having dabbled in changing what he did years ago, can return to the present and see the outrun of his meddling. However, with some shorter jumps of mere minutes he appears to just live his way back into the present.

Mitch Albom’s Twice has a similar premise with the protagonist Alfie Logan inheriting the gift of going back in time, but with the constraint that he can only revisit a particular moment for just one ‘second time.’ There are no third chances and wherever he goes Alfie must live his life all the way forwards from that point on, coming to terms in real time with however the consequences of the second bite of the apple turn out. Furthermore, once he has lost the love of someone, no amount of leaping back to second chances at different times will rekindle it. However, given the number of individual ‘moments’ in a life, Alfie is able to criss-cross his own timeline in ways that would surely make a film adaptation narratively impossible.

These two stories are perhaps the purest distillation of the do-over, second chance, Schrodinger alternate universes motif in spec-fic. Not whole lives to be relived, not restricted to a particular moment, and yet with the protagonist having total knowledge of how the alternate ‘abandoned’ timelines worked out.

These two stories are perhaps the purest distillation of the do-over, second chance, Schrodinger alternate universes motif in spec-fic. Not whole lives to be relived, not restricted to a particular moment, and yet with the protagonist having total knowledge of how the alternate ‘abandoned’ timelines worked out.

Tim decides to use his power to try and kick start his love life, though his efforts to seize second chances with potential romantic interests are often confounded by his efforts to avert career or personal disasters for family and friends. He does take several revisits to his ‘first intimate moment’ with his principal romantic partner so as to appear ‘more accomplished’ on that memorable occasion. Ultimately though, in keeping with the pun in the film’s title, Tim finally comes to the realisation that hopping around to tweak his timeline is futile and pointless and the real gift is to appreciate what we have in the moment.

Like Tim, Mitch Albom’s Alfie also uses his second chances to ‘enhance’ his love life – for example by finding out his teenage crush’s interests then taking a second shot to make himself into the kind of person that she would be interested in. Better acquaintance with the crush proves to him the shallowness of attraction based on appearance and persona rather than character. Like Tim, Alfie becomes entangled in the love of just one woman and a series of different second chances are burned through in an effort to make it work between them. Alfie’s ‘re-dos’ accumulate to almost an entire extra life (or more). I do have a slight unease about the ‘roofie’ overtones in some of those aborted timelines – women who Alfie has had encounters with that he recalls perfectly and they never know at all. In his head he has the memories of a promiscuous lothario and yet in the current timeline he presents to all around as faithful and monogamous.

However, Albom’s narrative plays into this problem with his protagonist having been named for Michael Caine’s character in his 1960s triumph Alfie. The cinematic Alfie leads a life of almost sociopathic indulgence, seducing and exploiting multiple women, yet ultimately ending alone. Late in life Albom’s Alfie views the film and awakens to the shallowness of his own exploitative existence. Recognising the mistakes he has made, he settles instead for using his gift to devote a life of unrequited love to cherishing and supporting the woman he has loved, missed and lost on multiple occasions. Though Albom does throw a delightful final twist into this salutary tale.

So Are Second Chances Worth it?

As with a lot of time travel stories, the reliving multiple lives tales are fraught with plot dilemmas. To relive just one butter-fly moment as Helen did in ‘sliding doors’ is an interesting exercise. However, in About Time Tim learns the perils of trying to tweak a long ago ‘sliding doors’ moment and failing to realise how that can unleash a cascade of unanticipated consequences – a domino chain of butterfly wings (if you will forgive the mixed metaphor). I have wondered if – given the chance to relive my youth – I might make a fortune with a cumulative bet on the sequence of Wimbledon Men’s Champions in the 1970s and 80s (finally finding a use for otherwise pointless sports trivia!). But who knows how the butterfly wing of my relived life might tweak John McEnroe’ serving arm in 1980 or 1981?

So are there any other ‘second chance/alternate timeline’ stories that you’ve loved – or any life moments you would like to take again? Would you be like the elderly widow I knew of recently who professed “If I had my time again I wouldn’t have married him” or would you follow the popular Etsy inscription and just assert “I’d find you sooner and love you longer?”

The fascination with those quirks of fate that shunt our lives onto a different track is perhaps shown in how phrases like Sliding Doors Moment and Groundhog day have entered popular culture. Ultimately stories like The Midnight Library and Twice give us the chance to exercise –and exorcise – those rued missed chances or different versions of our lives. Who wants to live a perfect life anyway – after all “To err is human.” And even if we did want to play with the “what if’s” of our lives, the ingenuity of human imagination – either our own or of the authors we read – is surely powerful enough to make a time machine unnecessary.

With my Goodreads bookshelves groaning under the weight of 761 books, I am reminded of the G.R.R.Martin line about how “A reader lives a thousand lives, while a non-reader lives but one.” And a thousand lives is more than Helen Quilley, Nora Seed, Ursula Todd, Harry August, Tim Lake and Alfie Logan lived all added together.