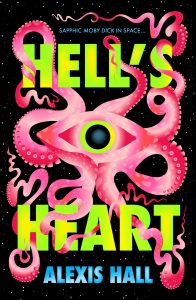

Interview with Alexis Hall (HELL’S HEART)

Alexis Hall (whatever pronouns) does not like writing biographies or talking about himself in the third person.

She lives in southeast England with their extensive collection of hats and four angry duckchildren.

C: Hi Alexis – thank you so much for discussing your new book with us!

A: No problem, thank you so much for inviting me!

C: I admit that I wasn’t quite sure what I was getting into based on the blurb and tagline: ‘Sapphic Moby Dick in space’ is pretty unique! I found myself caught up in the adventure immediately, hypnotised by the steady advance of the Pequod to its inevitable showdown at Hell’s Heart.

Can you share what inspired you to take on one of the great classics of literature in such a (literally) fantastic way?

A: I’ll be honest, I normally really struggle with the “what inspired you to do X” question but in this case there actually is an interesting story behind it.

Back in 2020, when the first lockdown started, I was looking for a project to take my mind off the abject misery and isolation of the whole thing. And what I ultimately hit on was reading a chapter a day of Moby-Dick. At the time, my reasoning was “this book is famously unbelievably long, so when the lockdown ends, and I haven’t got to the end of this famously unbelievably long book, it’ll feel like it went by more quickly.”

Obviously it didn’t quite go down like that, because as it turned out, no, 135 chapters was nowhere near enough. But I did do a daily tweet thread about the book and I built up a nice little community of people reading along with me. And because I’m, y’know, a professional writer I inevitably wound up thinking “how would I do a riff on this” and while I toyed with fantasy-and-it’s-dragons-not-whales, I rejected that for being just a touch too obvious and started mentally sketching out a concept for space-whale hunting on Jupiter.

Then I put the whole idea in a box for several years because I assumed I’d get laughed out the industry for trying to pitch “sapphic Moby Dick in space.” Some time later, my agent was meeting with an editor at Tor and she asked the obligatory “what’s the book you’ve always wished somebody would pitch” question, and the editor in question said “Moby-Dick as a romance” and so my agent said “funny you should mention that.”

And here we are.

C: Our protagonist, (known only as ‘I’) has bionic modifications and feels very human. She’s both simultaneously a parallel and a contrast with the very neutral/naive Ishmael of the original book; ‘I’ definitely contains multitudes, being nihilistic, self-deprecating and yet always very self-aware and even wise:

‘We’re bound together by webs of trust and betrayal and pain and comfort and triumph and humiliation and caring and apathy and life and life and life.’

I found myself frustrated by her as much as I liked her, but her honest storytelling was so refreshing amidst the madness of the plot.

Is she the only sane person on a ship of fools?

A: To kick off with, it’s very important to note that I’s bionic modifications are quite specifically that she’s trans. I think The endocrine synthesisers are there because her body doesn’t naturally produce oestrogen, and there’s a lot of other references to things that are basically deep future biotech equivalents of various forms of gender affirming surgery, only in a world where you have the technology to rebuild somebody’s entire skeleton.

In terms of whether she’s the only sane person on a ship of fools…that collides a bit with belief in Death of the Author because from a certain point of view “which of these characters is the only sane person on a ship of fools, or are any of them?” is a question I very much want people to be asking themselves.

You can make a case that it’s I (she’s the narrator, the audience surrogate, the one most inclined to make observations that she at least presents as dispassionate), that it’s Locke (they’re pragmatic, mission-oriented, and very big on the whole “what if we don’t get everybody killed” thing), that it’s A (she’s the one who realises the system is so rigged that the only bearable solution is to blow everything the fuck up) or that it’s Q (she’s the only one who hasn’t been totally broken by living in a late-stage capitalist dystopia). And it’s not really my place to decide that for other people.

C: The dry humour made me laugh aloud several times, from the fourth-wall-breaking narrative to the very obvious satirical jabs at contemporary religious traditions. How did you come up with the idea of the different ‘Churches’ across the galaxy? It makes sense that if humanity was so spread out, multiple points of view would naturally evolve (sorry!), but transforming Christianity into a completely selfish, capitalist doctrine – which underpins the corporations who rule over all – seems weirdly plausible given how some combine spirituality and business today!

C: The dry humour made me laugh aloud several times, from the fourth-wall-breaking narrative to the very obvious satirical jabs at contemporary religious traditions. How did you come up with the idea of the different ‘Churches’ across the galaxy? It makes sense that if humanity was so spread out, multiple points of view would naturally evolve (sorry!), but transforming Christianity into a completely selfish, capitalist doctrine – which underpins the corporations who rule over all – seems weirdly plausible given how some combine spirituality and business today!

A: Real talk: ten years ago I’d have thought the whole thing with the Church of Prosperity was too unsubtle and turned-up-to-eleven to be good satire. Today though…I mean you ask me where I got the idea and the answer is “the Prosperity Gospel is a real thing, and the version in the book is barely exaggerated from the real religious movement that really exists”. There’s a passage in the book where I gives the orthodox exegesis on Mark 10:25 about it being easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven and it’s barely modified from real world apologia. I’ve been in actual churches where I’ve heard people insist that “the eye of the needle” was actually some kind of gate into Jerusalem that camels had to kneel down to get past, and so what the passage really means is that the rich have to humble themselves before God and that just isn’t historically true. But the plain meaning of the passage is inconvenient for rich people, and rich people have been directing our understanding of religion for literal centuries.

The actual structure of there being three great churches, one that’s really pro-money, one that’s really pro-gun and one that’s really “pro-life” is sort of an extension of that but also, because Moby-Dick is, amongst other things About America it occurred to me that it would be cute to have the three major denominations being devoted specifically to “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness”, only “Life” means banning abortions, “Liberty” means guns and nothing else, and “The Pursuit of Happiness” means material wealth.

C: Another big difference from the source material is the… shall we say Boredom-Relieving Activities? There’s a lot of openly adult shenanigans here, and I can imagine lovers of the original clutching their pearls at the vulgarity! What this did was make me more deeply question I’s relationship with both Q and A (Queequeg and Ahab respectively), as they go from simple extracurricular time-wasting to satisfying kink, to genuine love and adoration.

What made you decide to explore these characters in such an intimate way?

A: So I think I’d push back very slightly on the extent to which this is a change from the source material. Obviously literally there’s not a ton of on-page sex in the original but homoerotic readings of Ishmael’s relationship with Queequeg in particular are some of the oldest readings out there. And of course the chapter that’s just one long joke about whale penises is directly from the original (chapter 95, The Cassock, if you’re interested).

It’s true that more mainstream Melvilleans (or, err, Dickheads as I understand they’re sometimes known) do get a little bit annoyed at the more sexual readings of the text, but something I think is really important to remember is that we shouldn’t hold queer history (including literary history) to a higher standard than we hold straight history. When modern people read Pride and Prejudice, they project the assumptions of a modern heterosexual love story onto a book that’s grounded in fundamentally different ideas about what love and marriage even mean. When you think about it, there isn’t any actual evidence in Pride and Prejudice that Elizabeth is attracted to Darcy in a sexual way. But in the 21st century we consider sexual attraction to be an essential part of a happy marriage and so we retroject that assumption onto a text where it simply isn’t a factor. To me, reading a sexual component into Ishmael’s relationship with Queequeg is no different. They share a bed, they kiss, at one point Queequeg literally says that they’re married. And yes you can make the argument that all of these things had a very different meanings in 1850, but so did heterosexual marriage.

I think the other thing I’d say is that while there’s no explicit sex in Moby-Dick, people would definitely have been banging on the Pequod. Churchill was describing the traditions of the royal navy as “rum, sodomy and the lash” in the last century, and he was probably riffing on a saying from at least a century earlier—which I understand to have been “rum, bum, and bacca”. What you could talk about in polite company or publish in a novel was very different from what actually went on.

As for why I chose to make it explicit and on-page: my background is in romance, I’m very accustomed to using sex as a way of driving characterisation. Basically it fit the tone of the book, the vibe I was going for, and the personality of the narrator for the text to be much more openly horny than you were allowed to be in the nineteenth century.

C: And I must say that I loved Q, the Weird Native Terran Barbarian, speaking mostly in Latin. My GCSE got dusted off and from the very first barroom insults, I knew that this would add a whole dimension on its own! There’s no translation given, so it’s up to the reader to look up what she’s saying.

Was this a little easter egg that adds to the story if folk make the effort? And are there more?

A: So there’s sort of two answers here. Firstly, depending on how you want to look at it, there are a tonne of easter eggs. There’s little references to the original book, to popular culture, to other bits of Melville lore and so on.

Secondly, and more complicatedly, there’s a tiny bit more to Q speaking Latin than pure easter eggs. You use the term “weird native terran barbarian” in your question and that coding was actually something I thought a lot about. The word barbarian originally comes from a Greek root referring to all non-Greek speakers and in its earliest uses in English tended to refer to people from beyond the bounds of the classical world. That is to say, it essentially meant people from outside the “civilised” world represented by people who spoke Greek or Latin. Because Q is a stand-in for Queequeg and because Queequeg intersects with some very complex, very 19th-century ideas about indigenous people and notions of (and there aren’t enough scarequotes in the world here) “civilisation” and “savagery” I wanted to make sure that I was framing her in a way which highlighted that while to I she’s, well, a weird barbarian, she’s actually from a nuanced culture that has its own shit going on. Very often, Q’s dialogue is direct quotes from classical sources and while there is an easter-egg element to that, it’s also about making it clear in a condensed way that she has access to a whole complex way of thinking that I just doesn’t. And of course a lot of the time, especially when they’re talking about religion, Q is directly quoting the Bible and this goes completely over I’s head because her conservative, hypercapitalist religion is so divorced from its origins.

C: While I don’t think I’ll ever see the original characters in the same light again, this is because you managed to make them far less dry and remote. I and Q are practical and passionate, allowing the reader to genuinely care for them as they travel across the oceans of space. However with A, you took one of the most complex characters in literature and managed to entirely convey their hypnotic charisma, motivation and soul. We’ve all heard of the obsessed sea-captain, out for revenge against the monster who took their leg, but I now understand why the crew continue to follow this doomed voyage despite all. That’s a remarkable achievement.

Did the portrayal of A ever seem like your own White Whale/Leviathan?

A: I’m not sure I’d go quite that far but I do think that writing somebody who has to be way cooler and more charismatic than you could ever be in real life is always a unique challenge. And obviously (we’re back to Death of the Author again) it’s up to individual readers to decide how well I succeeded but I feel like I did the best job I could.

The secret, I think, to writing that kind of character (and this really is something of a personal white whale) is to be scrupulously unselfconscious about the whole thing. Ahab in the original text is straight up, full-on Shakespearean and I tried to channel that energy. There’s bits in the book where A lapses into actual iambic pentameter and I did at times find myself looking at it and going “is this too much” to which I had to remind myself that the answer was “no, it’s exactly too much enough.”

I think possibly in this context the fact that I is a slightly less neutral narrator than Ishmael helps, because it means that the reader isn’t really seeing A objectively, they’re seeing her through the eyes of somebody who is helplessly and self-destructively in love with her. In general, I think, it’s a lot easier to see why somebody would feel a particular way about a character if you’re seeing them from the perspective of another character who actually feels that way.

C: And finally, quite a few quotes stayed with me as I moved through the story, but this one in particular sums everything up for me:

‘I want you to take these words and read them and imagine that you see your own life reflected in a life you could never have lived.’

Poignant and beautiful.

Thank you so much for taking us on this journey.

A: Thank you so much for joining me on it.

Hell’s Heart is out today from Tor! You can order your copy on Bookshop.org