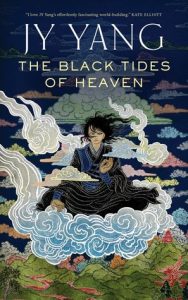

The Black Tides of Heaven by J.Y. Yang

The Black Tides of Heaven by J Y Yang does a lot of things that I wish more fantasy books would do. In addition to being so original in its history-infused setting that it has been cited as one of the first books in the “silkpunk” subgenre, it also earns the second half of that descriptor by actually examining the relationship between the characters and authority.

The Black Tides of Heaven by J Y Yang does a lot of things that I wish more fantasy books would do. In addition to being so original in its history-infused setting that it has been cited as one of the first books in the “silkpunk” subgenre, it also earns the second half of that descriptor by actually examining the relationship between the characters and authority.

Magic is representative of nothing, all too often in fantasy. The few books that do use it as a metaphor tend to fail to explore it very thoroughly, placing it into a dichotomy with technology in an attempt to layer on luddite argument about the loss of tradition and wonder in a scientific world. In the case of the Black Tides of Heaven, science and magic are one and the same, with the terminology and mechanics involved operating perfectly in harmony, the only distinction is that some of the characters, the “Tensors” of the series’ “Tensorate” title have an innate ability to manipulate these fundamental forces by will alone.

Of all the things that magic is used to represent in fantasy fiction, very rarely do I see it being equated with what I would consider to be the obvious metaphor: power. Political, military and economic power are all tied inherently to being a Tensor within the setting and one of the largest points of rebellion within the setting is centred on snatching that power away from those who were born with the pre-requisite natural abilities.

The strength of this book is its unflinching portrayal of familial relationships. The central characters are almost exclusively a family unit. The ways that they interact with one another, ranging from completely toxic to merely unhealthy, reveal a great deal about how the construct of “the family” works within the world of the Tensorate.

Another of the building blocks of the setting is the approach to gender. Rather than being assigned a gender at birth, people within the Tensorate spend their childhood using neutral pronouns before eventually deciding on their gender at around about the age of puberty. The magical-technology available removes any barriers to this set-up and the whole thing is treated as wonderfully mundane. The gender decision and “confirmation” are clearly an event within the character’s lives, but beyond that everything about gender seems to be wonderfully inconsequential.

Most fantasy books have a strong external plot, revolving around the pursuit of clear goals and achievements. The quest and revenge narratives that dominate the genre are almost exclusively external. Other genres, from romance to literary, place a greater focus on the internal plot, and the development of the characters as they grapple with their own decisions and shape the person that they are going to become. This book has a clear external plot revolving around the rebellion against the Tensorate, but ultimately the main thrust of the story is a journey of self-discovery ending in the protagonist achieving a sense of enlightenment when confronted with the opportunity to take an action of complex morality.

It is both the strength of the book and one of its most frustrating features that the moral choices of one character are weighted with so much more importance than the lives of others. There is something wonderfully Buddhist and self-indulgent about it.

I have yet to read the paired novella “The Red Threads of Fortune” which I have been informed is more action oriented and less introspective, but it is my hope that it resolves at least some element of the external plot, allowing the two books together to cover the whole gamut of the story being told, rather than letting this frustration linger.