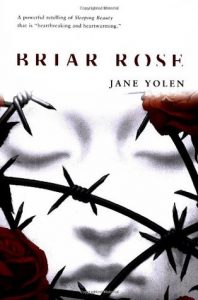

Briar Rose by Jane Yolen

“We are made up of stories. And even the ones that seem the most like lies can be our deepest hidden truths.”

“We are made up of stories. And even the ones that seem the most like lies can be our deepest hidden truths.”

An argument used to dismiss non-realist fiction, but specially Fantasy, is that it is pure escapism. Beyond the fact that everybody enjoys a bit of escapist entertainment now and then and there’s nothing wrong with that, this is a frustrating argument for those of us who know and love the genre because it elides how the fantastic can be powerfully and effectively used to explore real world issues. Just because a story is a fairy tale does not make it twee and inconsequential. Children know this, the families and story tellers who have passed down fairy tales from generation to generation knew this, Jane Yolen knows this. In her novel Briar Rose (1992), her entry in Terri Windling’s Fairy Tale series, Yolen uses the tale of Sleeping Beauty to talk about the Holocaust. The castle becomes the schloss in the village where the Jews are interned, the wall of rose thorns the barbed wire surrounding the concentration camp, the curse of sleep the sleep of death, the rosy red of Briar Rose’s cheeks the symptoms of gas poisoning. This is a bold approach, and in the hands of a lesser writer could run the risk of trivialising its subject matter. However, Yolen’s deft and sensitive writing pulls no punches and never shies away from the historical horrors she is portraying. Yolen uses the familiar comfort of the old fairy tale to talk about the unthinkable. It allows her to show us the horrors of the Holocaust with a shocking simplicity and immediacy. Although Briar Rose is an award-winning Young Adult book, Yolen never talks down to her audience, nor does she spare them the real life hardships and atrocities of the war. The novel is also a meditation on the importance of story telling, and particularly of fairy tales – the notion that sometimes the best way to approach a truth is through story, that there is value in tales that have happy endings despite the horror that precedes them, if they allow us to process that horror and to keep alive the memories of those who, in reality, did not survive.

Briar Rose follows the story of Becca Berlin, whose beloved Grandmother Gemma used to keep her entertained as a child by telling her the story of Sleeping Beauty. Following Gemma’s death, Becca finds herself unraveling the secrets of her Grandmother’s mysterious past life, which leads her on a trail to Poland, the extermination camp Chelmno, and Josef Potoki, the one surviving man who remembers Gemma’s story. Structurally, the novel is made up of three distinct strands – Becca’s present day investigations to uncover her Grandmother’s life story, Gemma’s retelling of the Sleeping Beauty story, which is retold at various times in Becca’s childhood in varying contexts, and Josef’s story of fighting the Nazis in the resistance during the war. Much of the power of the story derives from the skilful way these strands are interweaved. Gemma’s personal tweaks to her version of Sleeping Beauty highlight the parallels between the fairy tale and her miraculous rescue from the clutches of death at Chelmno by Josef’s group of partisan rebels. Gemma’s storytelling formed a large part of Becca’s personal growth and development into the woman she is today, forming the core of the special bond between grandmother and granddaughter. As the mystery of Gemma’s past is slowly revealed, we understand the importance of the Sleeping Beauty story. It allows Gemma to process and compartmentalise her traumatic past, but also to be able to talk about it and make sure that it is remembered, that for the sake of all those who did not survive something remains, in a way that she is able to communicate to her family. Thus the importance of the fairy tale is that it allows a way for us to talk about the unspeakable evil that was done to those who suffered and died in the concentration camps, we are able to approach the horrors of history afresh in a way that doesn’t reduce the suffering of millions to statistics on a page.

Briar Rose is also a study in heroism. The book effectively contrasts the idealised heroism of the prince in Sleeping Beauty with the actions of Josef and his fellow partisans during the war. Yolen shows us that while heroism exists in the real world, it is much more complicated because it is something done by flawed, everyday people. Josef’s journey to becoming Gemma’s prince who rescues her from a pit full of gassed victims does not shy away from the complexities of his experience. Rather than being a knight in shining armour, Josef starts off believing his privilege and connections will save him from Nazi persecution, but is eventually sent to a camp when he is outed for being gay. He suffers and witnesses terrible things at the camp, and eventually escapes to join the partisans in the woods, more out of necessity than any aspiration for heroism. The book is notable in how grounded and unromanticised its depiction of the partisans is. These are mostly just desperate people trying to survive, trying to fight back against the horror they have witnessed. However, their believability as ordinary human beings in extraordinary circumstances makes the acts of heroism they do commit all the more inspiring and believable.

The value of the fairy tale also lies in its promise of a happy ending. It allows us to retain hope in the face of adversity, to believe in times of hardship that evil can be defeated, that monsters can be overcome. However, the bittersweet nature of our relationship to such tales comes from the understanding that life does not give everyone neat happy endings. In the afterword, Yolen gently reminds us that the novel is a work of fiction – “I know of no women who survived Chelmno.” Becca’s story, with its comforting resolution and warm happy ending, both for Gemma who escapes to start a family in America and Becca who finds happiness at the end of her search for the truth, is also a fairy tale. This does not mean that its happy ending trivialises the suffering of real people, it means that it provides an inspiration of evil being overcome in order to help us remember everyone who in reality did not have a happy ending.