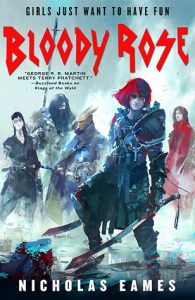

Bloody Rose by Nicholas Eames

(((Warning: The following review contains spoilers for Bloody Rose. Please take notice of the spoiler tags when reading – proceed at your peril!)))

(((Warning: The following review contains spoilers for Bloody Rose. Please take notice of the spoiler tags when reading – proceed at your peril!)))

If someone had told me that I would be reading the fantasy equivalent of The Great Gatsby when cracking open Bloody Rose, the newest in Nicholas Eames’ Band series, I would have arched an eyebrow and then nodded excitedly because that’s an incredibly cool idea. What might have surprised me was how much more I would enjoy Bloody Rose than I ever did The Great Gatsby, because while Eames may not quite have the melancholy romance of an F. Scott Fitzgerald, he has shown himself to be the world’s foremost authority in dropping Final Fantasy ref-bombs, and if that weren’t enough to impress, he also writes the kind of fantasy that is both immensely satisfying and deeply human.

The Nick Carraway to Rose’s Jay Gatsby is a young bard named Tam Hashford. Tam is the daughter of two world-famous mercenaries, and like Rose, contends on the daily with the need to fill the shadows of her fighting father and minstrel mother. Our story is told, with an ironic twist given the grisly fate of Saga’s bards in Eames’ first novel, through Tam’s eyes as she quickly becomes songstress to Fable, the world’s most famous band. Fable is comprised of Bloody Rose herself, the plot device of Kings of the Wyld whom we only ever met towards the end, her druin lover Freecloud, Cura, named the Inkwitch for the magical tattoos that cover her entire body, and Brune, a big bear of a man who can turn into, you guessed it, a large bear. Fable is to the current generation of Grandual what Saga, Rose’s father’s band, was to the former. Everyone knows the name Bloody Rose. Young girls dye their hair red in imitation. Crowds swoon when they arrive. There is no one fiercer than Fable, no one more daring, and despite a simple life of tavern waitressing, Tam is quickly embraced as one of the gang.

Fable’s task, as we soon learn, is to journey far to the north *SPOILER BEGINS* to battle a creature that even dragons fear, *SPOILER ENDS* despite the overwhelming fact that every other mercenary in the land is tying their laces and whetting their blades to fight a new monstrous horde heading south. This new army threatens to sweep across Grandual much like Lastleaf’s did in Kings had it not been stopped by the collective might of mercenary union. Rose doesn’t care because she wants to kill the fearsome creature up north and and then retire. Along the way, as any band worth its salt would do, Fable makes a tour of the arena circuit, continuing Eames’ notion that mercenary bands are simply more violent versions of rock groups. With those drives in place, we have Bloody Rose, and Eames, if you can believe it, takes us on an even wilder ride – one that manages to surpass even its predecessor (a fact that Rose would love to hear).

What is it that makes Bloody Rose better than Kings of the Wyld? Kings of the Wyld was a fairly traditional, and therefore safe, story about a group of aged mercenaries “getting the band back together” for one last rousing adventure. It was the perfect setup because it managed to avoid some of the more obvious tropes in fantasy – young “fated” people must save the world – while embracing others – monsters must be killed because they’re monsters. It was refreshing in its blend of new idea with old. But Bloody Rose transcends it because Bloody Rose is a solid, well-written fantasy novel that surprises often, takes risks (this is key), and leaves everything, and I mean everything, out on the battlefield. Kings of the Wyld was fun, but Bloody Rose is gods-damned epic.

Eames has improved in different ways too. I criticized his use of popular culture references in my review of Kings of the Wyld, and as I mentioned in my opener, things have not changed in that department, but his usage has become more subtle and therefore less jarring. A lute named “Red Thirteen” is noticeable only to someone who consistently has Final Fantasy 7 near the tip of their tongue, and it sounds legitimate enough as an instrument name to justify its use. That’s one example of many fine instances of author self-gratification, and I applaud Eames’ desire to continue in this way, and, more so, to improve at it. Some of the philosophy in Bloody Rose is more thoughtful as well. Eames asks questions of his heroes, constantly probing their motivations in ways that simply do not occur to most fantasy protagonists. There are undertones of racism and politics in this book, woven into the storyline with a deft hand, but there is never the sense that anyone is preaching. Bloody Rose asks its readers to think about these things and draw their own conclusions. There was certainly a hint of this in Kings, but it is improved in its sequel.

Eames character-work has leveled up as well. The members of Fable are complicated, each with a chip on their shoulders that usually involves their parents, and the slow unfolding of these personalities throughout the book makes them more relatable and interesting. *SPOILER BEGINS* Rose suffers from a crippling self-doubt because of how famous her father was and is, one that sees her risking her life in new and dangerous ways despite her new situation *SPOILER ENDS*. Cura has a past that would make any self-cutter weep, and again, one related to those who raised her. Brune’s angst takes a more visceral conflict, but manages to mirror his bandmates and perhaps even become cathartic for them. Even Tam, who grew up in a relatively loving home, has to deal with the death of her mother and the legacy left behind by such a large personality. The characters in Kings had fairly simple motivations – they needed to save and protect. Rose and her bandmates are anything but simple.

This is not a novel without flaws. Despite having complicated motivations, the characters in Bloody Rose can be frustrating – particularly Rose herself, whose own past calls into question some of her adult-level decision making. This is somewhat tempered by the real-world knowledge that rock stars traditionally are unreliable. Eames’ plot holes are also forgivable, namely those where villains decide not to kill the heroes when they have the chance, James Bond-style, and large events that might leave the fate of the Band in question were they not located squarely in the middle of the book. My biggest gripe with Bloody Rose, and with Eames worldbuilding in general, is that his magic system seems to have no rhyme or reason and to exist solely as a plot device. This is the George R.R. Martin school of thought, where magic should never be explained and authors are allowed to raise whomever they wish from the dead. As this book features a large amount of necromancy, some of this makes sense, but mostly the magic in Bloody Rose is there for cool set pieces. I don’t expect every author to go the Brandon Sanderson mile and explain every piece of pseudo-science behind their sorcery, but when magic exists only to be mysterious and powerful, it becomes frustrating, with a reader never knowing when the uber-wizard might sweep in and undo everything with the wave of a hand. As a reader, I like knowing where the limits begin and end.

Magical gripes aside, Bloody Rose surprises again as one of the best books of the year. I think that it’s better than Kings of the Wyld, which I loved and this should in no way reflect badly on that gem of 2017. Nicholas Eames has improved as an author, and he now has something more than just a good Dungeons and Dragons adventure under his belt (though Bloody Rose is certainly that). He has crafted a world and injected it with some serious lore, and I can’t wait to see where he takes us next.