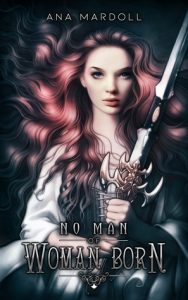

No Man of Woman Born by Ana Mardoll

This review may contain spoilers.

This review may contain spoilers.

“No Man of Woman Born” by Ana Mardoll is a collection of short stories, intending to be retellings of fairy-tales with a transgender twist. Each story takes a gender-phrased prophecy such as “no man can slay me” and subverts it through the protagonists’ oft-misunderstood gender identity.

Needless to say, I was extremely excited to read this collection. Fairy-tale retellings are a soft spot for me; I love how tightly they are plotted, with every element leading the reader to the inevitable resolution and, more often than not, to a deeper understanding of the moral of the story. When I saw the startlingly beautiful cover of the book, I knew for sure that I was in for a treat.

Ana Mardoll seems to come from the school of writers that leans on tropes when constructing their plots, so it should come as no surprise that my review of this work will be framed in a trope too: Death by a thousand cuts. There are several consistent issues throughout the book, none of them sufficient in themselves to spoil the whole, but all of them combining to make it a joyless experience.

The central conceit of this collection was the subversion of gendered prophecy, of the sort seen in Macbeth, or the subversion of that original prophecy that was seen in The Lord of the Rings. As such I was expecting to see several clever twists on this idea. Sadly, this was not to be. Every story came to the same conclusion with the character revealing their gender, or lack thereof, and then, almost always, murdering the antagonist.

The decision to have the stories centre on action was not playing to Mardoll’s strengths. The action scenes switch from being ridiculously clumsy in one story to being clinical descriptions of technical wrist movements in the next. I am not going to suggest that an author needs to get into a physical altercation before they can understand fighting, not any more than I would say that an author needs to have had sex before writing a sex scene, but the result is similarly lacking in emotional and visceral detail.

Just because an author hasn’t taken the time to familiarise themselves with the practicalities of sword fighting, I wouldn’t leap to accusations of laziness, but when you frame a character as a survival expert in one line and then have them drinking directly from a river in the next, I am going to be dubious about the depth of research that you have put in. In a strange way these inconsistencies of knowledge are consistent with the haphazard way that the characters have been constructed, with them switching from being cold and unemotional when confronted with dangerous situations to internally seething over the fact that a tree has been cut down to build the door that imprisons them.

Neopronouns are used throughout this book, and while I am not going to weigh in one way or another in the great debate that surrounds the use of them rather than the singular they/them, I will say that the decision to switch between neopronouns from story to story meant that every time I became accustomed to one and it had finally stopped pulling me out of the narrative, I was then confronted with a new one and had to start the process over again. A minor issue, but also another straw to break the camel’s back.

The biggest concern that I had with the stories as fairy-tales was the complete absence of morals or depth presented in any of them. The subversion of the prophecies meant nothing beyond the moment of violence, had no further-reaching significance and resulted in no growth for any of the characters. There was only one moment in all the stories where the narration came perilously close to making a point; a disenfranchised noble had lost her position of rulership because she had been born without magic and there was a comment about how unfair it was that this chance of birth had denied her the birth-right of dominion over common people that she deserved. It was almost harder for the author not to make the connection between these two “accidents of birth” than it would have been to acknowledge the similarity to rule by aristocracy, yet somehow they managed to swerve around it.

Self-publishing has been a wonderful thing for the queer community, allowing dissemination of important stories that would otherwise have been silenced by gatekeepers in traditional publishing, but the advent of easy self-publishing has also removed much of the support network that developing writers need. A few pointed comments from a good editor could have saved this collection and made it into something that I would have gleefully evangelised about, instead of the unkissed frog prince I hold in my hands.