To the Moon and back with Dublin Worldcon

Every so often I find myself picking up an old classic in an impulse to broaden my education. So it was when I plucked H.G.Wells The First Men in the Moon from a shelf in Belfast Waterstones. I finally went to the next stage of opening the book shortly before going on holiday in July, and then quickly found myself dragged down a rabbit hole that finally threw me out into the last panel I attended at Worldcon in August in Dublin.

You see, H.G.Wells in 1900 has his first-person narrator make a reference to Jules Verne’s earlier 1865 work Voyage to the Moon. Verne’s work in turn harks back, somewhat disparagingly, to Edgar Allan Poe’s The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall from 1835. All this fiction put me in mind of a pair of half-remembered Herge’s Tintin books from my youth, Destination Moon and Explorers on the Moon, written in 1954. So, I had the idea – in the spirit of Apollo 50 years on – for a short piece to compare and contrast how the science fiction of each generation had treated that alluring night-time objective.

But then at Dublin, first in an Apollo at 50 panel in Worldcon and then in a packed Monday panel on SFF and the Moon journey, I had a light shone on the dark and extensive recesses of human obsession with reaching the Moon described in fictions spread over thousands of years. So, this will be a mere scratch in the surface of that volume of literature.

Edgar Allan Poe – The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall

Poe chooses as his astronaut a bellows maker of Rotterdam, fallen into debt, who turns his suicidal impulse to leave this world into more of a literal exploratory desire to seek out a new world. The tale is substantially a first-person account in the form of a letter sent back to Earth by Pfaall. Alone of the four examples I picked, it gives an identified – indeed almost prominent role – to a woman, Pfaall’s wife.

Poe’s astronaut takes a balloon into space, in keeping with the technology of his age. He notes that balloonists of his era experience a degree of altitude sickness due to the thinning of the atmosphere. However, this is resolved with a macguffin of a device, to condense the thin air he assumes to fill the void of space into an atmosphere thick enough to breathe, within a canvas sealed basket beneath his voluminous balloon.

Poe is not entirely wrong in that balloons can ascend to stupendous heights, reaching the fringe of space. Felix Baumgartner in 2012 and Alan Eustace in 2014 were both carried around 40 km above the Earth’s surface. However, the canvas capsule of Poe’s imagination is unlikely to have been sufficient to protect them, and balloon technology would be unequal to the task of taking them the further 400,000 km journey needed to get to the Moon.

Also, while the interstellar void is not a complete vacuum, the extremely rarefied gases of which it is composed are mostly hydrogen with a little helium. Even “condensed” it would have afforded Pfaall nothing breathable, just a brief opportunity for an amusing squeaky voice effect.

Poe’s tale delves in great detail into the technicalities of the journey and his devices. This emphasis on the journey, rather than the destination, is a little frustrating, with the existence of an alien race on the surface of the moon rushed through in disappointing superficiality. This could be because Poe had intended to develop the short story/hoax with further instalments and the glib description of aliens was by way of a cliffhanger rather than a conclusion.

Pfaall is not a particularly endearing protagonist, being a somewhat self-absorbed individual who contrived to murder three creditors in the gunpowder-fuelled explosion of launching his balloon. It is, in that explosive launch, that Poe comes closest to the reality of Apollo 11.

Jules Verne – Voyage to the Moon

Jules Verne’s ebullient account of the Baltimore Gun Club’s mission to the moon comes in two parts. The first being a description of the design and construction of a great gun – a ‘columbiad’ – to launch a projectile at the moon. The second being an account of the journey of three explorers within the projectile. Verne’s omniscient narration has a style somewhere between fairy tale whimsy and Lemony Snicket reader asides.

Jules Verne’s ebullient account of the Baltimore Gun Club’s mission to the moon comes in two parts. The first being a description of the design and construction of a great gun – a ‘columbiad’ – to launch a projectile at the moon. The second being an account of the journey of three explorers within the projectile. Verne’s omniscient narration has a style somewhere between fairy tale whimsy and Lemony Snicket reader asides.

Verne’s in-depth research leads to some interesting parallels with the actual Apollo mission of over 100 years later – not least in the selection of Florida as the most appropriate launch point, or the three day journey time to the Moon. Other parallels – a three man capsule that ends up floating to await recovery on the Pacific ocean – are more serendipitous. Certainly, like other 19th Century authors who have invested greatly in research, Verne appears determined to share every detail of calculation and observation with the reader. This means parts of the book alternate in style between a physics textbook and a catalogue of observed lunar features.

Just as Poe before him glances over a key technicality (breathable air in space) with a macguffin, so too Verne deals with the body crushing force of being launched at 7 km/s from a cannon, with an implausible sleight of hand about water-cushioning within the projectile.

Verne revels in his description of the exuberant members of the Baltimore Gun Club, fresh from the murderous invention of the civil war. It makes for some entertaining aspects to the story filled, with flashes of humour and explosions. I found some peculiarly modern resonances as Verne portrayed an American spirit full of energy, obsessed with ever bigger guns, and determined to keep moving forward without thought of the consequences. For example, it is only once in the capsule en-route to the Moon, that the occupants give any thought to how they might return. This is, in someways, closer to the reality of the Apollo mission than one might think; the idea of doing any science, or having a purpose to visiting the moon other than just getting there, was almost an afterthought in the Apollo programme.

H.G.Wells – First Men in the Moon

Verne reputedly wrote in some chagrin about the engine of Wells’ story. Where Verne’s research would have filled the early lectures of a degree course, Wells’ had his scientist invent a material that shielded out gravity. He was inspired by the discovery not just of electromagnetic waves, but of the fact that radio waves could be shielded by a metal “Faraday” cage – as many of us who have struggled to get a mobile phone signal inside a steel framed building could testify.

Verne reputedly wrote in some chagrin about the engine of Wells’ story. Where Verne’s research would have filled the early lectures of a degree course, Wells’ had his scientist invent a material that shielded out gravity. He was inspired by the discovery not just of electromagnetic waves, but of the fact that radio waves could be shielded by a metal “Faraday” cage – as many of us who have struggled to get a mobile phone signal inside a steel framed building could testify.

Given that at Dublin Worldcon, Jocelyn Bell Burnell talked about the discovery and research into gravity waves – including new telescopes to detect them – it is perhaps not quite so fanciful to imagine that the action of gravity could be shielded against in the same way as radio waves.

Like Poe, Wells follows the first-person perspective of a businessman fallen into debt and bankruptcy who sees – in the moon – scope to restore his earthly fortunes. Like Pfaall before him, Wells’ Bedford is not a particularly appealing character; being first rather rude to the archetypal eccentric scientist Cavor, and then violent towards the moon-dwelling Selenites, and ultimately callous about the fate of an urchin set to guard his returning space capsule.

Bedford and Cavor discover a subterranean civilisation on the Moon, and a surface that flourishes with life during the long lunar day. Wells explores in some detail the nature of an alien civilisation and a kind of specialisation by selection amongst the Selenites” that goes way beyond the old 11+ and into Brave New World territory.

Wells’ notion of a vibrant living Moon is at odds with the dry-as-dust discoveries of Apollo astronauts. The rocks they recovered were so dry and devoid of moisture, that bone-dry by comparison would feel like being caught in the sudden deluge wandering between venues at Worldcon.

Wells’ notion of a vibrant living Moon is at odds with the dry-as-dust discoveries of Apollo astronauts. The rocks they recovered were so dry and devoid of moisture, that bone-dry by comparison would feel like being caught in the sudden deluge wandering between venues at Worldcon.

That said, the holy grail of lunar exploration – frozen water (OK ice) has been identified more or less where Wells would have expected it, in the constant shadow-lands deep in craters at the lunar poles. https://www.space.com/41554-water-ice-moon-surface-confirmed.html

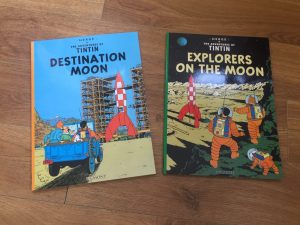

Herges – Adventures of Tintin Destination Moon and Explorers on the Moon.

My mother read me these when I was a child in Brazil in the 1960s. This involved translating them from Portuguese as she read, so I had never actually read them in English until this summer. Like his predecessors, Herge plucks at the leading technology of the time. Poe’s balloons, Verne’s guns, Wells’ electromagnetic waves and now nuclear physics. Herge is surprisingly accurate in his references to enriched Uranium 235 and the use of graphite moderators, but somewhat vaguer in how his nuclear engine actually works. This is particularly so, given that the “supplementary” rocket motor seems to do all the hard work of getting the rocket up into space.

Professor Calculus is even more of a polymath than Cavor, designing every aspect of the rocket and so essential to its success that a bout of concussion-induced amnesia threatens the entire project, where the Apollo mission had thousands of scientists covering all aspects of the science.

As with all Tintin books and some other works of fiction – there is a glib approach to head injuries. Bullets graze skulls, coshes bludgeon into oblivion, and always the heroes emerge immune to the inevitable subdural haematoma or lasting brain injury associated with anything more than a momentary loss of consciousness.

There are no women in Tintin’s lunar adventures – prescient perhaps of the way the role of women got airbrushed out of the Apollo programme. Recently revisited in the book and the film “Hidden Figures”, the role of women doing essential calculations to a high precision and accuracy proved vital to getting Neil Armstrong to the moon and back. It seems particularly fitting that the ambitious programme to return to the moon is named Artemis – after the god Apollo’s extremely capable and independent minded sister.

Worldcon

The panel on Apollo at 50 – graced, amongst others, by NASA astronaut Jeanette Epps – quickly explored one theme that all four of my fictional accounts totally ignored; namely, toileting in space. A complex subject that we humans shy away from. One Apollo astronaut was apparently so determined to avoid having to defecate in space that he took some high-grade Imodium substitute, and in consequence travelled the greatest distance ever recorded between successive movements – not a fact that you’ll see in the Guinness book of records!

The panel was not all tall toilet tales. The airbrushing and discounting of women in space exploration history was discussed in some detail. The total number of humans who have been in space might now make some analysis of its physiological impacts – for example, the damage prolonged experience of microgravity does to the human skeleton – statistically valuable. However, there is still a very low proportion of women and an astounding ignorance amongst the scientists in charge; e.g. a query as to whether one hundred tampons would be enough for one female astronaut on a 3 day mission to space.

The panel on “Shoot for the Moon: Lunar depictions in SFF” identified a welter of other fictional representations of journeys to the moon throughout history. This included mythologies and fantasies where people either: took an antigravity medicine; or got taken to the moon by a whirlwind of beyond-Oz proportions; or were launched by a giant spring; or were carried there by geese (apparently in the time of the Venerable Bede, barnacle geese were believed to winter on the moon); and even to dear old Wallace and Gromit on their grand day out in search of new supplies of cheese.

Hester Rook identified how Moon stories have often been a response to socio-political pressures of the time; for example a 1908 Chinese story about escaping earthbound corruption to create a new society on the moon, or another story about a prison colony based there. The moon as mirror is a popular theme, a screen onto which fiction has projected hopes and fears over the ages. Who knows what modern socio-political angst (climate change, social media, resurgent populism and demagoguery?) might find a contemporary fictional exploration on the moon.

Ian MacDonald gathered up some audience participators to demonstrate the scale of size and distance to the Moon. It should be remembered that managing a landing on the moon was akin to launching a stone and skipping it through a window across the width of the Atlantic ocean. As other panels discussed the Artemis project, it is clear that the original moon landings were a truly 21st century feat achieved with 20th century technology. In its way, perhaps not so distant from the crazed ambitions of Jules Verne’s Baltimore Gun Club in 1865.