Women’s Weird: Strange Stories by Women, 1890-1940 (Anthology Review)

“The dead abide with us! Though stark and cold

Earth seems to grip them, they are with us still.”– Mary Cholmondeley, ‘Let Loose’, 1890

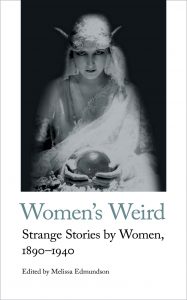

Women’s Weird: Strange Stories by Women, 1890-1940 is an anthology published by Handheld Press and edited by Melissa Edmundson. Edmundson is a scholar who specialises in women’s supernatural fiction in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. In her introduction, she describes how many of the women writers who pioneered Weird fiction and supernatural tales during this time period have been overlooked in favour of their more well-known male counterparts, such as H.P. Lovecraft, Arthur Machen and M.R. James. With Women’s Weird, she seeks to redress that balance by introducing the reader to a selection of Weird fiction and supernatural stories by women writers of the period. As a result, we get thirteen (naturally) wondrous stories by female writers ranging from Edith Nesbit, better known for her children’s fiction such as The Railway Children, to Charlotte Perkins Gilman, author of the crucial feminist story The Yellow Wallpaper. All the stories easily stand up to those written by their male counterparts, in terms of both the chills they deliver and how they map out the Weird as a distinct and innovative genre. They illustrate a vital history of women’s writing of Weird fiction that has gone underappreciated for too long.

Handheld Press have set a standard for the quality and insightfulness of their introduction, notes and reference material, and here it is particularly valuable. Edmundson’s introduction not only sets out her manifesto for the inclusion of women writers in histories of Weird fiction, it also provides a wealth of context about both Weird fiction and how it has been read and studied, and the individual authors included. Edmundson has selected a wide range of authors, including some who are now better known for writing fiction in other fields, and others who have largely fallen out of memory. This approach demonstrates how the Weird was born out of the supernatural tale but also how it transcends the limits of the pulp magazines it is so frequently associated with. Here are tales by Pulitzer Prize-winning Edith Wharton next to pulp fiction author Francis Stevens. The range of authors and stories suggests that the Weird is perhaps more an approach than a genre.

Handheld Press have set a standard for the quality and insightfulness of their introduction, notes and reference material, and here it is particularly valuable. Edmundson’s introduction not only sets out her manifesto for the inclusion of women writers in histories of Weird fiction, it also provides a wealth of context about both Weird fiction and how it has been read and studied, and the individual authors included. Edmundson has selected a wide range of authors, including some who are now better known for writing fiction in other fields, and others who have largely fallen out of memory. This approach demonstrates how the Weird was born out of the supernatural tale but also how it transcends the limits of the pulp magazines it is so frequently associated with. Here are tales by Pulitzer Prize-winning Edith Wharton next to pulp fiction author Francis Stevens. The range of authors and stories suggests that the Weird is perhaps more an approach than a genre.

The stories demonstrate the Weird’s ability to discomfort and disturb. From the earliest published story – Louisa Baldwin’s ‘The Weird of the Walfords’ from 1889 – we see a desire to stretch and subvert the limits of the traditional ghost story. ‘The Weird of the Walfords’ also introduces what will be a recurring theme across the anthology – the source of the horror coming from the domestic space, frequently portrayed through the gaze of a male character. The bed in ‘The Weird of the Walfords’ symbolises the protagonist’s sealed fate which he tries in vain to escape. Much of the story’s power comes from the comforting sheen of the familiar and the domestic being pulled away to reveal the uncomfortable tensions underneath. In Margery Lawrence’s ‘The Haunted Saucepan’, two men are terrorised by a saucepan which was used by a woman to poison her husband and her lover. In Margaret Irwin’s ‘The Book’, the protagonist makes a deal with the devil to further his career before realising the ultimate price will be the life of his family. D. K. Broster’s ‘Couching at the Door’ sees a prostitute exact revenge via a cursed feather boa. In ‘With and Without Buttons’ by Mary Butts, the witches in the story inadvertently summon a presence that makes itself known via ladies’ gloves. Across all these stories, the use of objects of domesticity as sources of horror is unsettling because it is unexpected, the Weird raising its head amongst the mundane, but also because it very effectively acts as a metaphor for abusive relationships taking place behind closed doors.

The figure of the abusive male crops up in many of the other stories as well. The animated hand in Mary Cholmondeley’s ‘Let Loose’ and the slimy tentacle thing in Eleanor Scott’s ‘The Twelve Apostles’ are all that remain of loathsome abusive men. The spirit in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s ‘The Giant Wistaria’ comes from a young woman who was murdered by her father for carrying an illegitimate child and ruining the family name. The spectral dogs in Edith Wharton’s ‘Kerfol’ avenge themselves on the young wife’s abusive older husband. These stories provide us with a new way of thinking about the Weird as it relates to lived experience – these are horrors not from the depths of unknowable space and time like Lovecraft’s monsters, but from the experience of being female in an inherently misogynistic and patriarchal world. That they are being used to generate similar feelings of hopelessness and existential despair is telling. This is a subject further hinted at in Elinor Mordaunt’s ‘Hodge’, in which the prehistoric man woken in the modern age finds himself unable to function removed from his own time and social context.

When talking of Weird fiction, inevitably the spectre of Lovecraft comes up. In the context of Lovecraft, one of the most interesting stories in the volume is Francis Stevens’ ‘Unseen – Unfeared’. Edmundson perceptively points out in her introduction how the story is essentially an inversion of one of Lovecraft’s most notoriously racist stories, ‘The Horror at Red Hook’. Whereas in Lovecraft’s story the racist viewpoint of the protagonist is upheld, in ‘Unseen – Unfeared’, the protagonist’s racism is treated like a drug-induced illness, a fault in his perception which very nearly causes his doom. This difference in perspective between Stevens and Lovecraft extends to the story’s conclusion, where the protagonist, despite the horrors he has witnessed, makes the choice to abandon the dismal Lovecraftian worldview for something more hopeful.

A highlight of the collection is Edith Nesbit’s ‘The Shadow’. Nesbit really ought to be as well known for her horror fiction as her children’s fiction, and indeed as one of the masters of horror fiction, and ‘The Shadow’ is an excellent example of why. With masterful control of voice and character, Nesbit weaves a tale of a married couple plagued by a mysterious shadow creature that is one of the most vivid and disturbing tales in the whole book. Also most impressive is May Sinclair’s ‘Where Their Fire Is Not Quenched’, perhaps the strangest story in a book of very strange stories, and certainly the most experimental in style of all the works included. Sinclair’s nightmarish portrayal of an adulterous couple who are doomed to an eternity of passionless sex is thoroughly disturbing, and in many ways represents a culmination of the themes, ideas and fears that are explored throughout the book.

Women’s Weird is an essential read for any fan or scholar of Weird fiction, and we are indebted to both Handheld Press and Melissa Edmundson for performing this service. The anthology successfully brings to light a much overlooked aspect of the history of Weird fiction in a compellingly readable and frequently surprising collection. I find myself excited by the new avenues of reading and thought it has opened up to me, and would very much like to see a volume II at some point in the future. As with all Handheld Press releases, the book is thoroughly annotated and features a gorgeous cover.

Women’s Weird is available now.