Info-dump Equity and The Matrix (Guest Post by M. D. Presley)

Info dumps are bad.

So says everyone.

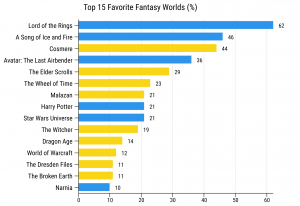

At least, according to the internet. Google “info dump” and the first few hits after the definitions are articles on how to avoid them. Yet Tolkien spent a whole chapter in both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings info dumping not only what hobbits looked like but including their ancestry, technology levels, and favorite foods. And Tolkien is still considered the greatest worldbuilder of them all according to a recent poll I conducted for my upcoming book on worldbuilding:

So, how then do we reconcile these two opposing views? How can info dumps be both reviled and yet an integral part of the most beloved world-builders’ works?

Most people object to info dumps because the large blocks of information disrupt the immersive experience. It’s the size and quantity of the information that people hate. Or at least that’s what most people assume. In the Magic Without Rules episode of Writing Excuses, Brandon Sanderson maintained it’s not the amount of information that people object to, it’s the placement of the information. He called this ‘info-dump equity’, which he meant in the economic sense that the author must build equity with the audience before springing an info dump on them. In effect, the audience must be invested enough to want the information, which the author willfully withholds until—like a wizard—it arrives at precisely the right time.

But before the author can withhold the information, the audience must crave it. They must be hooked first before they can be reeled in.

In ages past, the drug of choice for hooking audiences was the prologue, which has also fallen out of fashion. At least in the written word. The prologue is still going strong in the world of film, where it goes by the moniker of the ‘cold open’ or ‘teaser’. The latter name is more appropriate in that it teases the audience with a question that it promises to answer so long as they stay with the story. To do this, they create a mystery, which most folks will hover at the edge of their seats for if they believe a reasonable answer will arrive. In film, the teaser is usually a short series of scenes that arrive before the main story kicks off with the protagonist(s) in their mundane reality, which will soon be upended by the arrival of the mystery established in the teaser.

But for fantasy and science fiction works, the mystery in the teaser has some extra nuance. By their very natures, fantasy and science fiction are expected to break the laws of nature as we know them. Reality itself is a plaything in these genres, which means they can create their mystery for info-dump equity with new worldbuilding details. And, conveniently enough, this can be done by mastering another of Sanderson’s contributions to the understanding of worldbuilding: soft and hard magic systems.

This subject is worthy of its own dedicated discussion, which is why it is worth getting the information directly from Sanderson on his blog or online writing lectures, but it basically boils down to the fact that soft magic systems are those that the audience does not understand the rules to, whereas hard systems are those where the audience is aware of the system’s rules, abilities, weaknesses, limitations, and cost. One of the strengths of soft magic is that it is mysterious, whereas hard magic benefits from being able to be used to solve plot points without being seen as deus ex machina. This hard/soft understanding of magic systems also pertains to worldbuilding as a whole in that audiences either know the rules to the world overall, or they do not.

But that understanding of the worldbuilding rules is not static in the least and can shift from soft to hard (although moving from a hard to soft understanding would most likely be considered inconsistency on the author’s part). In fact, it’s the shift from soft to hard that creates info-dump equity. In the teaser the author demonstrates something impossible in our world, something wondrous and mysterious and without context. If properly applied, this incongruity with reality will hook the audience and ensure they stick around to see how this impossibility is later explained.

In most cases, the audience and protagonists discover the rules to the world at the same time, thus hardening the world around them, and although not a fantasy story, the best example of this comes from The Matrix. The movie opens with an oblique reference to ‘the one’, and then within seconds Trinity is facing off against the cops, at which point she unveils the iconic bullet-time kick that set the world afire. Then there’s some running up the side of walls and a race across roofs complete with some impossible jumps. And it’s the impossibility of these feats that’s the point, to the extent that one cop explicitly remarks “that’s impossible.”

It’s also soft worldbuilding in its purest, most concentrated form. Trinity and the agents are shown disregarding the laws of nature, leaving the audience wondering how and what this has to do with ‘the matrix’. This is the central question that has been raised and will be used to tease the audience along for the first act of the film. And, because the scenes were compelling, this works as an ample hook to reel the audience in.

This impossibility is then immediately juxtaposed by Neo and his everyday mundanity in an almost paint-by-number adherence to the hero’s journey. More soft worldbuilding occurs as Neo is drawn deeper into the plot, now at the hands of Agent Smith as he steals Neo’s mouth and bugs him. All this is done to find Morpheus, who Neo and the audience both hope will finally provide elucidation once he’s found.

This is a masterclass in info-dump equity in that the goal for the first act is information. The audience now wants answers as much as Neo does, for Morpheus to shine a light on and explain the mystery they’ve encountered numerous times now. The desire for answers is so strong that the Wachowskis double down on it by promising answers so long as Neo takes the red pill. The need for explanation of the soft worldbuilding details is such that it propels him and the audience into the second act when Neo awakens into his new world.

Shortly thereafter, nearly 40 minutes into a 150-minute film, we finally get our elucidation as Morpheus sits Neo down and explains to him the matrix. This is pure, unadulterated info dump, and although there are visuals to back up the imparted information, it is a scene dedicated explicitly to explanation that breaks another writing tenant of ‘show-don’t-tell’. And, based upon where you believe the info dump really begins, the scene lasts somewhere between five and seven minutes. Of pure telling-not-showing.

And yet these are some of the most iconic scenes of The Matrix. They are its core conceit and an unforgettable set piece to a movie that changed cinema. With an info dump.

But now here is where things get interesting. The beginning of the second act is what Blake Snyder called “fun and games” in that this is the meat of the movie, the part where they explore their core conceit. In The Matrix, this is another unforgettable, iconic scene where Neo tests his newfound kung fu against Morpheus. It’s also another info dump dressed up in some beautiful visuals. And, at its core, it’s the moment that the soft worldbuilding truly transfers to a hard understanding of the world. Through Morpheus’ instruction and a few character trials, Neo learns the rules of the world, and through him the audience does as well. And although info dumps are supposed to be boring and break immersion, this is the ‘fun and games’ section of The Matrix.

But now here is where things get interesting. The beginning of the second act is what Blake Snyder called “fun and games” in that this is the meat of the movie, the part where they explore their core conceit. In The Matrix, this is another unforgettable, iconic scene where Neo tests his newfound kung fu against Morpheus. It’s also another info dump dressed up in some beautiful visuals. And, at its core, it’s the moment that the soft worldbuilding truly transfers to a hard understanding of the world. Through Morpheus’ instruction and a few character trials, Neo learns the rules of the world, and through him the audience does as well. And although info dumps are supposed to be boring and break immersion, this is the ‘fun and games’ section of The Matrix.

And it works.

Mostly this is because they created info-dump equity in teasing the rules for an entire act before finally revealing them to the ravenous audience. It also helps that they elegantly wove the worldbuilding rules into the plot and character development as well. And they did this all with a mystery they teased in their prologue.

Now it should also be noted that creating info-dump equity with mystery is not a ‘mystery box’, which is a concept popularized by JJ Abrams in which the audience is strung along by one mystery after another. Alas, as Marshall Ryan Maresca laments in the first season of Worldbuilding For Masochists podcast, the mystery box is unsatisfying because it never successfully answers the audience’s burning question about the worldbuilding (*cough* Lost *cough*). In effect, the mystery box establishes info-dump equity by hooking the audience with the initial mystery, but then instead of paying off that mystery by hardening the soft worldbuilding details, it plies new soft mysteries upon new mysteries.

It should also be noted that there is no requirement for hardening soft worldbuilding details. A world can remain soft and mysterious throughout, as many of the most popular fantasy series are. Nor is there a requirement to use info-dump equity, which Tolkien certainly eschewed. But any writer wielding their worldbuilding details should be aware of the strengths and drawbacks of each approach and find the one most useful in the moment.

Worldbuilding for Fantasy Fans and Authors releases August 13th. mybook.to/WFFAA

[…] acts as a bit of a prologue, which is something that has fallen out of vogue in novels (although, as I pointed out before, prologues work great for info dump equity). Some readers claim to skip them entirely so they can […]

[…] I enjoyed this look at Conan and am looking forwards to getting into MD Presley’s series on World Building at the Fantasy Hive […]